We left Achilles at rock bottom. His rage launched a sequence of events that were not only devastating for his comrades, but the person he cares about most in the world is dead. His desire for revenge then led him to slaughter untold numbers of Trojans, yet killing the man who killed his best friend brought him no peace. He is not genuinely reconciled to his primary antagonist Agamemnon. The breach of trust suffered when nobody in the Greek army stood beside him to prevent Agamemnon from violating custom in a bid to punish Achilles had not been mended. There is no evidence that he has reconstructed a faith or developed alternative beliefs that motivate his behavior and help him act meaningfully in the shadow of his inevitable death. Achilles demonstrates no pride or enjoyment from victory and honors bestowed upon him by the Achaean army. He continues to abstain from food, drink, sleep, and intimate relationships. His ongoing rage drives him to callous, disgusting acts. If that’s not rock bottom, I don’t know what is.

We are past the climax of the story; Achilles has triumphed over his antagonists. Agamemnon has lavished him with gifts and a public apology and Hector is dead, yet Achilles’ situation is essentially unchanged or worse than when we started, and he appears no closer to emerging with the heroic stature we hope and assume he will achieve. The final stage of a drama is sometimes called the denouement which derives from the French verb “nouer” which means to bind, or tie in a knot. Achilles is certainly emotionally tangled and physically bound up; his anger, hatred, rejection of social norms, the suffering of others, and violent aggression have only tightened the grip of those knots. Does Achilles find any comfort or peace? If so, how?

I’ve tried to make the case that Achilles is more than just a spoiled demi-god, and that his emotional turmoil has its roots in conflicts with which we can identify, but his responses have only exacerbated a miserable situation and made him less sympathetic. I suspect this is intentional on Homer’s part; one of the most common epithets for Achilles in The Iliad is “god-like”. There are plenty of reasons one might apply this description to Achilles. Homer has described the deaths of over 200 heroes, all of whom, if Homer is to be believed, were stronger and more magnificent than men are now; so we have a vivid picture of the type of combat in which Achilles has been engaged on the front lines for nearly a decade without being killed or seriously wounded. That is pretty impressive, god-like, stuff. Homer doesn’t give much physical description of Achilles, but the cannon of the Trojan War Epic Universe says that his physical beauty matched his prowess in battle and capacity for rage. His divine parentage from a mother whose brief presence on Olympus in book one resulted in a fit of rage and accusations against Zeus from Hera suggests he may be a very attractive man and earn the description “god-like” by virtue of his physical attributes. However, Homer has Patroclus, Achilles’ closest friend, voice another way in which Achilles is “god-like”. Recall the words he used when returning to Achilles’ tent after Hector had breached the Acheaean camp fortifications:

Healers are working over them, using all their drugs, trying to bind the wounds— But you are intractable, Achilles! … You heart of iron! He was not your father, the horseman Peleus—Thetis was not your mother.

Never. The salt gray sunless ocean gave you birth and the towering blank rocks—your temper’s so relentless.

His rage is implacable and unwavering, and drives him outside the bounds of normal human behavior. There’s a reason the second essay in this series was called “No variableness, neither shadow of turning”. Achilles is like the gods in his unswerving determination, and that unwillingness or inability to change and alter his course has profound consequences. In that essay I argued that mortality renders our choices and actions intrinsically meaningful because they are associated with an opportunity cost, and therefore represent values about who we mean to become and our vision for the world. I argued that immortality, absent that opportunity cost, could potentially impair making meaningful decisions and therefore contribute to the types of anti-social and morally objectionable behavior common among the Olympian gods. I feel the primary evidence for this conjecture lies in the fact that immortal gods are often described and presented as unchanging. Negative consequences of their decisions don’t induce any discernible period of reflection or altered behavior; the gods seem stuck in their eternal molds. In Achilles, Homer combines the barrier to growth characteristic of immortals, inability to change, with the fundamental feature of humanity, mortality, resulting in an enormous quantity of suffering. This may feel like an incredibly onerous way to arrive at such a trite observation, but the whole point of these journals is the business of seeking and finding the universal insights and wisdom in a text I had previously undervalued, and I think the way Homer develops the need and desirability of change in Achilles is interesting. So there.

Now that Achilles is not only aware of his mortality, but has felt the sting of betrayal, the devastation of personal loss, and the guilt of moral agency, all in the service of self, will he remain “god-like” and implacable, or will he grow and change?

The first inkling we have that Achilles is changing to reconcile with his reality is when he returns to camp after slaying Hector when he announces to the Myrmidons:

Charioteers in fast formation—friends to the death!

We must not loose our teams from the war-cars yet.

All in battle-order drive them past Patroclus— a cortege will mourn the man with teams and chariots.

These are the solemn honors owed the dead.

And then, after we’ve eased our hearts with tears and dirge, we free the teams and all take supper here.

He acts not out of pain, anger, or self-interest, but out of love and obligation to another. His progress is not without impediment, he still bears significant animosity toward Hector:

Farewell, Patroclus, even there in the House of Death!

Look—all that I promised once I am performing now:

I’ve dragged Hector here for the dogs to rip him raw—and here in front of your flaming pyre I’ll cut the throats of a dozen sons of Troy in all their shining glory, venting my rage on them for your destruction!”

So he triumphed and again he was bent on outrage, on shaming noble Hector— he flung him facedown in the dust beside Patroclus’ bier.

After everyone is in tears they feast in remembrance of Patroclus and toast their glorious victory. Everyone but Achilles. When the army attempts to celebrate him he rebuffs their call:

He spurned their offer, firmly, even swore an oath: “No, no, by Zeus—by the highest, greatest god!

It’s sacrilege for a single drop to touch my head till I place Patroclus on his pyre and heap his mound and cut my hair for him—for a second grief this harsh will never touch my heart while I am still among the living …But now let us consent to the feasting that I loathe.

And at daybreak, marshal Agamemnon, rouse your troops to fell and haul in timber, and furnish all that’s fitting, all the dead man needs for his journey down the western dark.

Then, by heaven, the tireless fire can strike his corpse— the sooner to burn Patroclus from our sight— and the men turn back to battles they must wage.”

So he insisted.

Everyone else enjoys the feast, and sleeps well in camp, but Achilles makes his way alone to the shore and collapses from exhaustion. He falters in his oath not to sleep, and Homer uses this moment to transform the haunting sense of regret and obligation Achilles feels into a literal one. Patroclus’ ghost appears.

Hovering at his head the phantom rose and spoke: Sleeping, Achilles? You’ve forgotten me, my friend.

You never neglected me in life, only now in death.

Bury me, quickly—let me pass the Gates of Hades.

They hold me off at a distance, all the souls, the shades of the burnt-out, breathless dead, never to let me cross the river, mingle with them … they leave me to wander up and down, abandoned, lost…

But one thing more. A last request—grant it, please.

Never bury my bones apart from yours, Achilles, let them lie together

Achilles awakens and replies:

“Why have you returned to me here, dear brother, friend?

Why tell me of all that I must do?

I’ll do it all.

I will obey you, your demands.

Oh come closer! Throw our arms around each other, just for a moment— take some joy in the tears that numb the heart!”

In the same breath he stretched his loving arms but could not seize him, no, the ghost slipped underground like a wisp of smoke … with a high thin cry.

And Achilles sprang up with a start and staring wide, drove his fists together and cried in desolation, “Ah god!”

This moment conveniently occurs just as Dawn stretches out her rosy fingers at the beginning of a new day, and Achilles gets right to work. Men and teams of horses are dispatched to Mount Ida to gather timber to make a pyre that measures a hundred feet on each side. There’s a touching bit about Achilles remembering a sacrifice/ bargain his own father made to the river god Spercheus and the token of that covenant he bears; his own long/ uncut hair (Samson vibes). Achilles reasons that since he knows he will die and the River God cannot make good on the hoped for promise, that he and all the Myrmidons should cut a lock of hair for Patroclus. Patroclus’ favorite dogs and horses are also sacrificed on the pyre alongside a dozen Trojan captives. It’s a pretty grizzly affair. As the funeral pyre burns and Achilles reconciles his debt to, and grief for, Patroclus, he takes another step and begins to genuinely reconcile with Agamemnon:

And now the sunlight would have set upon their tears if Achilles had not turned to Agamemnon quickly:

“Atrides—you are the first the armies will obey.

Even of sorrow men can have their fill.

So now dismiss them from the pyre, have them prepare an evening meal.

We are the closest to the dead, we’ll see to all things here.

But I’d like the leading captains to remain.”

Achilles has the army’s back and appreciates that they’ve been hard at work gathering materials for the funeral, and now they’re all in tears and he recognizes they need food and rest, but he also makes a point of having Agamemnon dismiss them.

With the help of the gods of the winds the fire burns all night, and Achilles can finally rest, “And at last Achilles, turning away from the corpse-fire, sank down, exhausted. Sweet sleep overwhelmed him.”

After he finally gets some unhaunted sleep Achilles takes more steps in mending damaged relationships with the Achaean army and its leaders. He holds funeral games for Patroclus. There are chariot and foot races. There are contests of martial prowess like wrestling, and archery. Most commentaries I’ve encountered spend little to no time on the funeral games, but I think they’re far more than mere formality or filler material. In them we see Achilles’ good humor blossom as he commands the attention of the whole army, arbitrates disputes, and Homer preaches the age-old wisdom that it is in fact better to give than to receive, as Achilles takes from his own treasures he’d been honored with over the years and redistributes his prizes of honor to others. There are numerous events that demonstrate Achilles’ character and growth, but I’ll examine one in detail. The outcome of the chariot race. It turns out Homer anticipates the drama of NASCAR racing by several millennia

This guy named Eumelus had the best horses and jumps out to an early lead, but Apollo and Athena play some dirty tricks and the upshot is that Eumelus crashes and is injured, but after an extended pitstop he manages to finish a distant last place. Consequently Diomedes takes first, but an even more exciting and controversial moment determines second place. Antilochus, Nestor’s son, who is driving the slowest team of horses takes an inside line on the turn and aggressively edges out Menelaus at a narrow spot in the track and wins second prize. Some might call that good old-fashioned racing, but you’ll recall the House of Atreus is not accustomed to losing chariot races, and Menelaus objects. There’s quite the kerfuffle at the finish line. The guy with the fastest team comes in last and the second in command of the army is beaten by the youngest competitor with the slowest team. Achilles finds the whole thing comical. In a moment of mirth he proposes to give second prize, an unbroken mare, to Eumelus as consolation for what everyone could see was divine intervention that cost him the race.

Seeing him there the swift Achilles filled with pity, rose in their midst and said these winging words:

“The best man drives his purebred team home last! Come, let’s give him a prize, it’s only right…

So he said and the armies called assent to what he urged.

And now, spurred by his comrades’ quick approval, Achilles was just about to give the man the mare when Antilochus, son of magnanimous old Nestor, leapt to his feet and lodged a formal protest:

Achilles—I’ll be furious if you carry out that plan!

Do you really mean to strip me of my prize?

You pity the man?

You’re fond of him, are you?

You have hoards of gold in your tents, bronze, sheep, serving-girls by the score and purebred racers too: pick some bigger trophy out of the whole lot and hand it on to the man, but do it later—or now, at once, and win your troops’ applause.

I won’t give up the mare!

The one who wants her— step this way and try— he’ll have to fight me for her with his fists!”

The stakes are different, but we’ve heard words like these before, and we know how Achilles navigated similar waters then; what will he do now that he is the one with the power?

Achilles smiled, delighting in Antilochus—he liked the man immensely.

He answered him warmly, winged words: “Antilochus, you want me to fetch an extra gift from my tents, a consolation prize for Eumelus?

I’m glad to do it.

I’ll give him the breastplate I took from Asteropaeus.

It’s solid bronze with a glittering overlay of tin, rings on rings. A gift he’ll value highly.”

He asked Automedon, ready aide, to bring the breastplate from his tents. He went and brought it, handed it to Eumelus.

The man received it gladly.

Achilles knows the betrayal of having the rules of the game switched on him, and he quickly corrects course. He knows the social bonds that bind them together and seeks to strengthen them, not assert his authority over a perceived challenge to his authority. Unfortunately there’s more friction to resolve.

But now Menelaus rose, his heart smoldering, still holding a stubborn grudge against Antilochus.

A crier put a staff in his hands and called for silence.

And with all his royal weight Atrides thundered, “Antilochus— you used to have good sense!

Now see what you’ve done!

Disgraced my horsemanship—you’ve fouled my horses, cutting before me, you with your far slower team.

He goes on to demand that Antilochus swear that he hadn’t cut him off intentionally. I guess to do so was considered poor form. Antilochus, who was just so indignant about having his prize taken quickly defers to Menelaus and apologizes for youthful exuberance and indiscretion, and volunteers to give his prize to Menelaus.

Bear with me now. I’ll give you this mare I won—of my own accord.

And any finer trophy you’d ask from my own stores, I’d volunteer at once, gladly, Atrides, my royal king—anything but fall from your favor all my days to come and swear a false oath in the eyes of every god.”

With that the son of magnanimous old Nestor led the mare and turned her over to Menelaus’ hands.

And his heart melted now…

“Antilochus, now it is my turn to yield to you, for all my mounting anger … you who were never wild or reckless in the past.

It’s only youth that got the better of your discretion, just this once—but the next time be more careful.

Try to refrain from cheating your superiors.

No other Achaean could have brought me round so soon, but seeing that you have suffered much and labored long, your noble father, your brother too—all for my sake— I’ll yield to your appeal, I’ll even give you the mare, though she is mine, so our people here will know the heart inside me is never rigid, unrelenting.”

One interpretation of this exchange is that Homer is reinforcing a value of subservience to hierarchy. This is possible, but I think something else is going on here, I think there is a greater trend of demonstrating reconciliation without violence. The power dynamics of hierarchy, and the desire of individual honor and glory are subordinated to the desire to maintain and strengthen relationships.

Achilles’ was injured by Agamemnon and felt betrayed by the army and he let that sense of betrayal drive him to neglect the relationship he treasured most and everyone lost. He learned the hard way that prioritizing his own honor and drive for personal glory above the relationships that gave him genuine happiness was an enormous mistake. Prioritizing virtues of friendship: accepting constructive feedback, correcting mistakes, and giving generously, has brought a smile to his face and quickly resolved nascent conflicts. His own example inspires others to do the same. I said way back in my discussion of Timé and Kleos that I thought understanding the questions Homer asked his audience required significant cultural background, but that his solutions would not. There are lots of reasons people have been reading Homer for nearly 3,000 years, the essentials of great storytelling: compelling narrative, interesting characters, and linguistic prowess are all present. I suspect innumerable forgotten tales share these attributes. The brilliance of teaching the virtue of peaceful reconciliation by honoring relationships within one of the most famous war stories in world history is genius level stuff one would expect only from a graduate of Wharton school of business.

Before moving on from the funeral games I’ll cite one last example of Achilles’ change of attitude and behavior. The final competition of the games is the javelin throw. It never happens.

And now the spear-throwers rose up to compete, Atrides Agamemnon, lord of the far-flung kingdoms, flanked by Idomeneus’ rough-and-ready aide Meriones but the swift runner Achilles interceded at once:

“Atrides —well we know how far you excel us all: no one can match your strength at throwing spears,

you are the best by far!

Take first prize and return to your hollow ships while we award this spear to the fighter Meriones, if that would please your heart. That’s what I propose.”

Who, exactly, is the “Best of the Achaeans” now?

I’ll let you decide.

After the games are over Achilles has healed a lot of wounds. He’s reconciled with the army and Agamemnon, but he hasn’t untied all the knots that bind him. He remains heartbroken, and he takes his pain out on Hector’s body.

The games were over now.

The gathered armies scattered, each man to his fast ship, and fighters turned their minds to thoughts of food and the sweet warm grip of sleep.

But Achilles kept on grieving for his friend, the memory burning on … and all-subduing sleep could not take him, not now, he turned and twisted, side to side, he longed for Patroclus’ manhood, his gallant heart—

What rough campaigns they’d fought to an end together, what hardships they had suffered, cleaving their way through wars of men and pounding waves at sea.

The memories flooded over him, live tears flowing, and now he’d lie on his side, now flat on his back, now facedown again.

At last he’d leap to his feet, wander in anguish, aimless along the surf, and dawn on dawn flaming over the sea and shore would find him pacing.

Then he’d yoke his racing team to the chariot-harness, lash the corpse of Hector behind the car for dragging and haul him three times round the dead Patroclus’ tomb, and then he’d rest again in his tents and leave the body sprawled facedown in the dust.

How do you reconcile with a dead enemy? Where does he find comfort for this pain? There has been so much loss in the battles it seems like he could find a sympathetic ear anywhere he looks. Homer’s answer is found in honoring the custom of Xenia. I’ve discussed the universality of the principle, and one of the powerful examples of Xenia offered in the text elsewhere, but the way in which Homer employs the concept in the conclusion of The Iliad is worthy of further examination.

Everyone, even the Olympians, can see that Achilles is stuck in a moment and can’t get out of it; at the same time Troy is devastated. Hector, heir to the throne, husband and father, hero to the masses, and the city’s only hope for victory over the Achaeans is dead. Not only have they lost their greatest champion, but they can’t even mourn him properly because his body is being dragged around behind Achilles’ chariot. This arrangement fails to serve the interests of all parties and Zeus launches a plan to rectify the situation. Thetis, Achilles’ mother, is summoned and told that Achilles must give Hector’s body back to the Trojans, and she makes her way down to speak with him. Priam is visited in a dream and told that he must go down to the Achaean camp and ransom his son’s body.

Upon awakening Priam begins preparing for the journey. His wife thinks he’s gone insane. The last thing they’d heard from Achilles was that he wanted to cannibalize Hector, the idea for the king himself to enter the camp of the army that has besieged his city for a decade and approach their son’s killer, the most devastating weapon of mass destruction in the Mediterranean basin, is beyond the pale. Eventually, Hecuba is reassured by a favorable omen, and preparations are completed. A wagon is loaded with all of Troy’s greatest treasures, and Priam is given a heart wrenching farewell by his family and city as he departs at sundown.

As Priam approaches the River Scamander he meets a young man who greets him warmly and claims to be an Achaean familiar with the layout of the encampment. When he learns the king’s errand, he swears to guide him safely to Achilles. The young man is actually Hermes in disguise, sent by Zeus to assure the success of Priam’s journey. You and I may find this moment to be heartening, the Olympians really do care, look at what lengths Zeus has gone to in order for this whole thing to work. That is fair enough, but take a moment to consider the symbolism of this scene. Among others, one of Hermes’ roles is that of a psychopomp, it was his duty to escort the souls of mortals to the River Styx on their way to Hades, the unknown country from whose bourn no traveler returns. Having Hermes show up in this moment highlights the peril of Priam’s journey: A nocturnal river crossing descending to a place of the dead to retrieve a loved one from which he is unlikely to return. A variety of mythologies feature stories of people entering the underworld attempting to retrieve someone from the land of the dead, and things typically do not go as planned. You and I know Zeus has actually ordained all this, but Priam is operating on a dream and an eagle flying on his right side, his acts are courageous displays of faith in the rightness of his cause and devotion to his son and city. Hermes uses his power to protect and guide Priam to Achilles’ lodge. There he reveals his identity, and takes his leave. Priam must approach Achilles, the symbolic lord of the underworld and ruler of the dead, alone.

There’s a knock at the door and when Priam reveals himself Achilles and his companions just about fall out of their chairs.

The majestic king of Troy slipped past the rest and kneeling down beside Achilles, clasped his knees

and kissed his hands, those terrible, man-killing hands that had slaughtered Priam’s many sons in battle.

Awesome—as when the grip of madness seizes one who murders a man in his own fatherland and flees

abroad to foreign shores, to a wealthy, noble host, and a sense of marvel runs through all who see him— so Achilles marveled, beholding majestic Priam.

His men marveled too, trading startled glances.

Priam explains his plight, and pleads for Hector’s body.

Revere the gods, Achilles!

Pity me in my own right, remember your own father!

I deserve more pity … I have endured what no one on earth has ever done before— I put to my lips the hands of the man who killed my son.”

Those words stirred within Achilles a deep desire to grieve for his own father.

Taking the old man’s hand he gently moved him back.

And overpowered by memory both men gave way to grief.

Priam wept freely for man-killing Hector, throbbing, crouching before Achilles’ feet as Achilles wept himself, now for his father, now for Patroclus once again, and their sobbing rose and fell throughout the house.

Then, when brilliant Achilles had had his fill of tears and the longing for it had left his mind and body, he rose from his seat, raised the old man by the hand and filled with pity now for his gray head and gray beard, he spoke out winging words, flying straight to the heart:

“Poor man, how much you’ve borne—pain to break the spirit!

What daring brought you down to the ships, all alone, to face the glance of the man who killed your sons, so many fine brave boys?

You have a heart of iron.

Come, please, sit down on this chair here… let us put our griefs to rest in our own hearts, rake them up no more, raw as we are with mourning.

Following a moment of catharsis he agrees to return Hector’s body. This whole sorry chain of events began when a father approached the Greek camp begging for his child, and was rejected. Agamemnon insulted and mocked Chryses as a display of his power and greatness and disaster followed. Achilles’ heart is touched and rage and sorrow are transformed into vulnerability, empathy, and kindness. Ransoming a captured enemy is customary in this context, can I credibly claim acts of kindness and reconciliation with what follows?

The tension and hostility of two deaths and a decade of war has not totally evaporated. There’s an exchange that reveals the fragility of this moment. Once Achilles accepts the ransom Priam suggests that now that he’s killed Hector, and has the most valuable treasure of Troy, Achilles can go home in peace.

A dark glance—and the headstrong runner answered, “No more, old man, don’t tempt my wrath, not now!

My own mind’s made up to give you back your son.

A messenger brought me word from Zeus—my mother, Thetis who bore me, the Old Man of the Sea’s daughter.

And what’s more, I can see through you, Priam— no hiding the fact from me: one of the gods has led you down to Achaea’s fast ships.

No man alive, not even a rugged young fighter, would dare to venture into our camp.

Never— how could he slip past the sentries unchallenged?

Or shoot back the bolt of my gates with so much ease?

So don’t anger me now.

Don’t stir my raging heart still more.

Or under my own roof I may not spare your life, old man—suppliant that you are—may break the laws of Zeus!”

Perhaps this is all a ruse aimed at disabling the Achaean army? Buy off Achilles in a last ditch effort to win the war. We know that’s not true, and in a way so does Achilles. This moment vexed me at first. The tender scene of shared grief nearly gives way to more violence. Why? After a bit of thought I think it has to do with Achilles’ transformation and rejection of the ethos of Timé and Kleos. Priam’s suggestion that he “take the money and run” implies Achilles is motivated by the pursuit of fame and glory that drives so many others. Achilles hasn’t surrendered Hector’s body because the price of the ransom was right. He knows he’ll die on these shores and never enjoy any of his riches. He is obeying the will of Zeus and was genuinely moved by the personal contact with Priam, and the idea that money and fame has any place in his calculations was probably insulting. He even feels like he may be betraying Patroclus once more, “Feel no anger at me, Patroclus, if you learn— even there in the House of Death—I let his father have Prince Hector back.” The thing is, once Priam is disabused of the notion he has “bought off” Achilles, the acts of generosity and kindness come in rapid succession.

Achilles could simply drag the body over to Priam, take the loot, and send the old man back to Troy, but he doesn’t. Homer told us Achilles’ men were just finishing up their evening meal when Priam arrived, but after this exchange with Priam, Achilles himself prepares a feast, “So come—we too, old king, must think of food.

Later you can mourn your beloved son once more, when you bear him home to Troy, and you’ll weep many tears. Never pausing, the swift runner sprang to his feet and slaughtered a white sheep as comrades moved in to skin the carcass quickly, dress the quarters well.” He selects royal garments from the ransom and sends servants to wash, anoint, and clothe Hector’s body to present it to Priam. He has a bed made up for the old man to stay the night, “Achilles briskly told his men and serving-women to make beds in the porch’s shelter, to lay down some heavy purple throws for the beds themselves and over them spread some blankets, thick wooly robes, a warm covering laid on top.” Achilles thinks of contingencies and arranges things to minimize the probability any of the other Argive leaders will discover Priam is in camp. Priam is no longer on a mission of desperation in enemy territory, he is Achilles’ guest. There’s a word in our culture for one who gives “aid and comfort to the enemy”. Treason. For Achilles there’s a virtue that supersedes fame, glory, and loyalty to his army. Xenia.

The Trojan War began with a violation of Xenia when Paris, a guest of Menelaus, abducted Helen. It’s fitting that Homer closes his tale about the war with a striking example of Xenia in action. I claimed earlier the formation of this new relationship helps heal some of Achilles’ wounds. Homer illustrates this in several ways. Not only is he no longer talking about cannibalism, but for the first time since Patroclus’ death, Achilles seems genuinely interested and engaged in a proper meal. He also finally sleeps peacefully with his special lady, “deep in his sturdy well-built lodge Achilles slept with Briseis in all her beauty sleeping by his side.”

In one last gesture of kindness Achilles asks Priam how much time will he need to properly mourn and bury Hector, “One more point. Tell me, be precise about it— how many days do you need to bury Prince Hector? I will hold back myself and keep the Argive armies back that long.” Priam says that it will take 11 days, and Achilles assures him there will be peace. Hermes awakens Priam early in the morning, the return voyage is uneventful, and they cross the River Scamander at dawn. Priam assures his subjects they can venture outside the city walls to gather supplies on Mount Ida without fear of abuse and preparations are made. The Iliad ends with a description of Hector’s funeral.

But when the tenth Dawn brought light to the mortal world they carried gallant Hector forth, weeping tears, and they placed his corpse aloft the pyre’s crest, flung a torch and set it all aflame…

Then they collected the white bones of Hector—all his brothers, his friends-in-arms, mourning, and warm tears came streaming down their cheeks…

They placed the bones they found in a golden chest, shrouding them round and round in soft purple cloths. They quickly lowered the chest in a deep, hollow grave…

And once they’d heaped the mound they turned back home to Troy, and gathering once again they shared a splendid funeral feast in Hector’s honor, held in the house of Priam, king by will of Zeus.

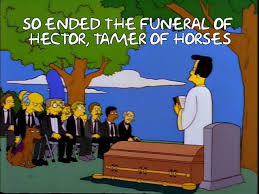

And so the Trojans buried Hector breaker of horses.

That’s it. That’s how it ends. No arrow striking Achilles’ heel. No Trojan Horse. No fiery sack of the magnificently wealthy city. No masts of Greek ships descending over the horizon into the setting sun. We fade to black after the promise Achilles made to Priam for 11 days of peace has been honored. I started this series discussing how The Iliad wasn’t “the story of the Trojan War” in the way I expected it to be told. Perhaps that says something about how I’ve been conditioned to receive war stories. I expect a measure of adversity and death, but I also expect victory and triumph or tragic defeat. Definitive, historical turning points defined by outcomes on the field of battle. Among the oldest examples of writing in the world are descriptions of the victories of pharaohs, emperors, and kings over their enemies. The victory stele of Naram-Sin, inscriptions on the walls of the mortuary temple of Ramses the third, and The Book of Joshua are all examples from the ancient Near East. Stories immortalizing conquest and triumph have always been, and almost certainly will forever continue to be, consistent box-office hits. At this point, emphasizing the universal pursuit of Timé and Kleos feels like Achilles dragging Hector’s body around Patroclus’ burial mound on the daily. As I’ve noted, Homer honors this convention, but he also highlights its drawbacks and demonstrates the superior benefits of other virtues. He does not paint either side as clearly good or evil, he inundates the audience with the bloody reality of conflict, the devastating loss of honorable people, and he denies us the resolution of definitive victory or defeat on the field of battle. We’ve heard these stories for thousands of years and The Iliad does not neatly fit the mold of an honest-to-the-gods war story. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: there’s a reason people have been reading this thing for 3000 years. If it was just a well told, prototypical war story I suspect it would have found its way into the dustbin of history long ago. There is conflict and adversity. There is violence, and long dark nights of the soul. There is even a victory of sorts. Xenia triumphs over betrayal. Homer may have invented what is now one of the oldest tricks in the world of books, he tells an inspiring, universally human, story wrapped up in a moment of legendary import for his audience. By framing the war and Achilles’ heroics in this way Homer is able to teach very different lessons than we expected when went off to war with him. The Muses have sung their song of the rage of Achilles and the dissonant minor chords that dominated the score at the onset have given way to a triumphant melody featuring soft harmonies with which we can all hum along.

In my first discussion of Xenia I noted the practical benefits of facilitating travel and trade in the ancient world. Here, Homer highlights the deeper meaning and advantages of the principle. To welcome another into your home or to cross the threshold of a stranger when you’re far from the world you know are acts of faith in humanity. Providing the basic human needs of food, relief, and shelter for another demands care, empathy, and compassion. Knowing that you will care for those who seek relief from you and the belief that you can expect similar treatment when you’re in need are statements of hope. The practice of Xenia says something about what type of world you want to live in. It is a declaration of who you mean to be.

800 years after Homer, another Mediterranean storyteller taught about the power of Xenia:

On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

“What is written in the Law?” he replied. “How do you read it?”

He answered, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”

“You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.”

But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

In reply Jesus said: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’

“Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?”

The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him.”

Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise.”

Human life is fragile. Chance and fate are beyond our control and the rain falls upon the just and unjust alike. We are surrounded by walking wounded, and we ourselves have been or someday will be among their ranks. As best we can tell, we don’t have much company in our immediate vicinity. As we make our way through lives of limited duration the choices we make matter. There may not be a divine plan nor reward of eternal life for living well. Our names and deeds will almost certainly be forgotten, no Kleos aphthiton. Our ability to “change the world” is limited and highly contingent. This is all to say we neither know nor control the outcomes of our actions, nonetheless while we’re here we can choose to act in accordance with a vision for a world in which we want to live as people we want to be. We can live like we mean it.