As I mentioned in a prior essay I’ll do my best to neither assume knowledge of, nor import too much information from extra-textual stories about the Trojan war when discussing the primary topics of interest in this series. I think it worth a moment to make a brief catalog of things that are either explicitly mentioned or are alluded to with such definition and clarity that we can assume with confidence that they are understood as true for Homer and his audience based upon the existing narrative. A relationship between Thetis, goddess and daughter of Nereus the Old Man of The Sea, and Peleus yielding Achilles the greatest most amazing weapon of mass destruction in the Mediterranean basin, the abduction of Helen by Paris and the refusal of the Trojans to yield to Achaean (The Iliad never calls the anti-Trojan allies “The Greeks”, they’re most commonly called Achaeans) demands to return her, a protracted siege of Troy, a division within the pantheon regarding which army and fighters to support. There may be more, but that’s all I can come up with at the moment.

I’d like to point out one thing that is definitely not explicit and I’d argue is also not clearly assumed in the text, but which is considered common knowledge about one of the main characters: Achilles’ invulnerability except at his heel. Not only is Achilles’ relative invulnerability not present in The Iliad, but various aspects of the story make no sense if this fact is assumed, and if it is true it undercuts one of the main themes of the narrative. Why would Achilles bother with any armor if he is, or believes himself to be invulnerable? Not only does he possess armor in the beginning of the story, but after Patroclus is killed while wearing Achilles’ armor and Hector takes takes it back to Troy, Thetis, his mother, the one who would presumably be the most aware of his invulnerability by virtue of having dipped him in the River Styx, makes him promise to await a new suit of armor before returning to battle. She then gets Hephaestus to make armor for her son; there’s basically an entire book of the Iliad devoted to describing the armor, especially the shield, divinely crafted for Achilles. It all makes no sense if there’s an assumption of invulnerability. Additionally, the gods themselves are wounded in battle. Aphrodite famously drops her own wounded son, Aeneas, whom she is attempting to rescue from imminent death when the Achaean warrior Diomedes stabs her with a spear. Aphrodite is the goddess of passion and desire, so maybe “wounded love” is an image Homer developed for a reason. However this potential exception fails to explain why Ares, the god of war, is also wounded in Book 5 of the Iliad. The gods are by definition immortal, but it seems obvious they can be wounded. It therefore seems unlikely that Achilles, a mortal, would be the sole possessor of physical invulnerability and yet need to wear armor like everyone else, therefore I reject it, at least within the confines of The Iliad. The point is Achilles is definitely mortal and vulnerable to death, and he knows it, he talks about it explicitly in Book 9, and in my opinion this reality is essential for understanding why this text has remained relatable for 3000 years.

Thanatoi is the word most often used to describe humankind in the Iliad. The word derives from thanos the word for death (Stan Lee and the folks at Marvel weren’t being subtle) and thanatoi roughly translates to the dying, or the dying ones. The primary distinction between humans and the gods in The Iliad is that humans are constantly dying, and definitely will die at some point, and the gods are immortal and cannot die despite the fact that they can be wounded and feel pain and complain about it to daddy Zeus (see Book 5). The Iliad takes for granted that humans live in the constant shadow of death. The finale of the poem does not describe Greek victory, or a rousing speech of triumph, but relates the solemn rites of the funeral of Hector, breaker of horses.

We actually do the same in English. We describe our less than perfect selves as “mere mortals”. Mortal of course derives from the Latin “mors” meaning death. In the stories we tell about ourselves, we are also the dying ones. There is a vision of a soul and an afterlife in Homeric epic described in The Odyssey, but it is neither hopeful nor inspiring. The shades of mortals live a dim half-life in the realm of Hades, they cannot talk and are not self aware in the absence of a drink of blood to temporarily rouse their consciousness. It is definitely not something one lives one’s life preparing for. Individuals and cultures grappling with death in their art is nearly universal and The Iliad is most definitely a meditation upon that which is worth risking one’s death, the high stakes one man’s choices carry for others, and how one reconciles with one’s own death and the death of loved ones. This reality may offer some insight into the characterization of the Olympian gods in The Iliad.

Those of us raised in an Abrahamic tradition of monotheism devoted to a capital G God who is transcendent and characterized by superlative virtuosity are apt to find Homer’s gods perplexing. How could an entire culture believe in and worship gods who consistently engage in rape/seduction of mortals, innumerable cruel acts of petty jealousy, and who regularly allow family drama to spill over into mortal affairs often with devastating consequences? It struck younger versions of me as preposterous. I’m not looking to start fights with theists, but as I’ve grown older I’ve come to recognize that the Olympians aren’t alone among the gods in having believers willing to worship them despite sharing tales of their behaviors that fall far outside that which we would accept from a human. Anyone familiar with the contents of Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, or Joshua will have an appreciation for this fact. As much as I’d love for this to devolve into a discussion of what makes a god worthy of worship, I’m going to focus on the fact that the Iliad is not a theologic text, and therefore Homer’s depiction of the Olympians need not accurately reflect the actual content of ancient Greek beliefs in the gods, nor the diversity of belief within the society. The evidence we have suggests that his wasn’t an unrecognizable portrayal, but one may reasonably assume his choices about how he portrayed them serves an artistic purpose. What could that purpose be?

If humans are characterized by their mortality and the gods by immortality perhaps this distinction has some trickle down effects upon behavior? I think there’s reason to believe Homer’s buffoonish presentation of the gods in the Iliad intentionally counterpoints the gravity of the events for the humans involved. In Book 12 The Trojans are advancing on the Greek camp. Both sides are bringing immense resources to bear and the business of death is unavoidable. Sarpedon, a son of Zeus, a prince of Lycia, allied to the Trojans, pulls a comrade in arms, Glaucus, aside and waxes poetic about why they must engage in this insanity.

Ah my friend, if you and I could escape this fray and live forever, never a trace of age, immortal, I would never fight on the front lines again or command you to the field where men win fame. But now, as it is, the fates of death await us, thousands poised to strike, and not a man alive can flee them or escape—so in we go for attack! Give our enemy glory or win it for ourselves! 12: 310-328

Paradoxically the fact that he is mortal is exactly what prompts Sarpedon to engage in high risk behavior that, spoiler alert, (are there really spoiler alerts for 3,000 year old stories?) will result in his own death. He is not alone in this belief. This rallying cry is repeated many times in slightly different forms by a variety of characters throughout the text. Does this make sense to you? Does the fact that you are mortal inspire you to risk your life? We all cope with mortality in our own way, and there’s a very specific cultural ethos reflected in Sarpedon’s words, but I think the insight reflected in these types of speeches is the recognition that it is the fact that our lives are limited that gives our choices meaning.

I hope I’m not the only one who has had a phase of life close, and looked back with regret about some of the choices I made, or some of the things not done because I failed to appreciate the temporary status I enjoyed. My older patients often inform me that youth is wasted on the young. I often think about all the time I wasted as a kid which could have been spent in more productive and fun activities. I regret the moments I failed to connect more with my mother when, more than almost anyone else in the world, I knew she was dying. It’s a terrible thing to have literally just closed your notes on gastrointestinal malignancies in preparation for a test the next day to answer a phone call from your mother wherein she informs you a recent CT scan showed a mass in the head of her pancreas. I don’t wish a similar experience upon anyone. The point is that our time and our choices as humans, as the dying ones, matter precisely because our time is limited. When I chose to pursue a career in medicine it required a decade of my life to bring it to fruition. Humans only live 8 decades if we’re lucky. The price of that choice was approximately 12.5% of my life. Even with that stark assessment I don’t currently regret that choice, but the fact is there are opportunity costs in human life. When a mortal chooses to become a specific type of person, to develop a talent, or a virtue, to try and change or improve her world, it comes at a cost of time and therefore a non-zero portion of one’s life. In a very real sense we sacrifice our lives to the ideals and visions we chose to pursue with our time and effort.

Immortals, on the other hand, have a very different calculus, or lack thereof. If you are genuinely immortal, then by definition you have all the time in the universe and therefore the choice to cultivate talents, virtues, or not has no real urgency. If it takes a decade to resolve a conflict or bring a project to completion: who cares? When the denominator of your cost analysis is infinite, the numerator doesn’t matter. To an immortal time has no real value. If time has no value then the reflection of desire or personal determination represented by making a choice is arguably diminished. For an interesting exploration of this I’d direct the reader to Steven Peck’s novella A Short Stay In Hell. Human expressions of love and commitment are generally sacrifices or compromises of our time, abilities, and personal interests. I would very much like to read and write more in the evenings, but I spend time attending band concerts, shuttling youths to various activities, volunteering as a scoutmaster, helping neighbors move, etc. Because human life is finite, the choice to express love is a choice to sacrifice one’s life. Once again the value of the choice is diminished if the resource of time is infinite. Many definitions of the word value boil down to the differences in quantity and quality of a finite resource. Therefore I think it fair to question if an immortal being can develop values, and attributes that require the sacrifice of time and effort. Can you genuinely sacrifice something of which you have an infinite supply? If nothing can actually be ventured, can anything be gained? Perhaps this is one reason why the Olympians remain in a state of arrested development, never growing beyond the specific idea they personify despite their immortality? Perhaps the ancient Greeks believed they couldn’t? Perhaps Homer had an insight about how their immortality robbed them of growth?

How far fetched is this theory? Is there any cultural or textual evidence of this type of conjecture? Clearly the business of a factual survey of immortal beings, their behavior, growth, change, and development or lack thereof is a ludicrous idea. That hasn’t stopped humans from trying for the past few thousand years. Feel free to examine the scriptural text of your choice. I’ll confine myself to the Olympians and try to cite relevant examples from common myths and Homer. Let’s consider Zeus, the King of Gods and Men. Apart from being the wielder of the lightning bolt, Zeus is best known for his marital infidelity to Hera and galivanting about with countless goddesses and mortal women. Io, Europa, Semele, Alcemene, Antiope, Danae, Lamia, and Leda all fell pray to the seductions or forced desire of Zeus. These liaisons often famously brought the wrath of Hera upon these women and their offspring. She tricked Semele, the mother of Dionysus into asking Zeus to reveal himself in all his majesty, and consequently she died on the spot. Dionysus was then allegedly grafted into Zeus’s thigh for the remainder of his gestation. She attempted to kill Heracles, the son of Alcemene, as a toddler by having serpents released into his crib. This failed, but later he was driven temporarily insane by Hera and killed his own wife and children. His twelve labors were the price of recompense for the act. Helen, she of the face demanding the launch of a thousand ships, was hatched from his affair with Leda, so in a sense Zeus sowed the seed of the Trojan War. If the story about his arranging the marriage between Thetis and Peleus was primarily to subvert the fate associated with her offspring (her son would be greater than his father) because he knew he’d eventually want to father a child with her is true, then the birth of Achilles, the golden apple, and the judgment of Paris and the devastation of the Trojan War are all linked to Zeus’ predilection for infidelity. After the creation of men, Zeus grew weary and frustrated with them and attempted to wipe them out with a flood that left only two survivors. This flood business seems to be a common trait of near east deities. This repeated, callous disregard for the consequences of one’s actions is in line with the emotional intelligence of a toddler or sociopath, not a wise being worthy of devotion. Maybe the reason Zeus never learned from the fallout of his actions wasn’t because he chose not to, but because he was constitutionally incapable.

Similarly Hera’s revenge was consistently aimed at the mortal women who succumbed to the seductive charms or force of Zeus in these relationships is another example. There’s a saying about fury and the scorned woman, but eventually you’d think she’d reserve her disdain for the repeat offender wielding the outlandish power asymmetry in these relationships, and not the victims of his appetite. I guess victim blaming got started early in human history? Maybe her failure to develop compassion is not the sign of an eternal shrew, but a manifestation of the meaninglessness of mortal consequence for an immortal?

Earlier I mentioned an episode when Aphrodite, the mother of Aeneas, drops him on the battlefield after being injured by Diomedes. If you’re like me, this is exactly the opposite of the traditional veneration of the sacrifice mothers make for their children. Compared to an OB/GYN or an L&D nurse, I haven’t been involved in a lot of childbirths, but I’ve seen more than most people and after seeing and learning of the risks and sacrifices mothers frequently make for their children I can say with confidence that my shock at Aphrodite’s behavior is not merely a function of the privilege I have from a life filled with loving maternal examples. When the chips are down, and Aphrodite experiences a slight, temporary pain from a wound that definitely will not kill her, she abandons her son. She is, by definition, given to passions and rash decisions, but maybe this choice also reflects the inability of an immortal mother to genuinely sacrifice for her offspring. Ever think about Hephaestus? There is a story wherein Hera reportedly tossed Hephaestus, her own son, off the top of Mount Olympus when she saw his deformity.

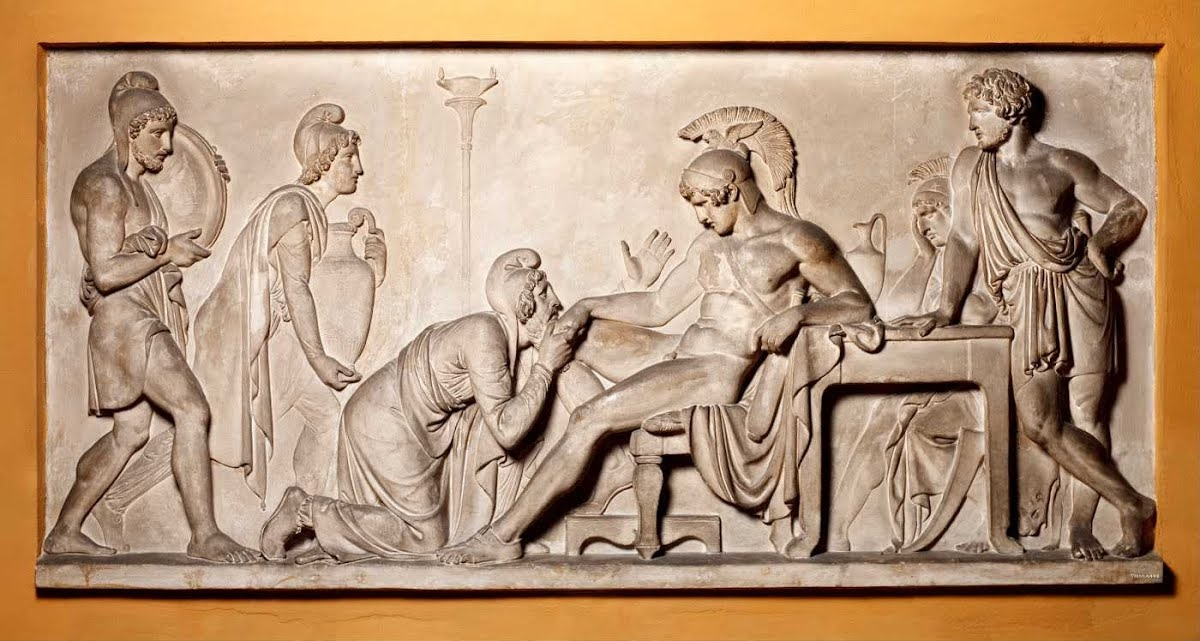

Diomedes Wounding Aphrodite When She Tries to Recover the Body of Aeneas by Arthur Heinrich Wilhelm Fitger

At several points in The Iliad Athena, Hera, and Poseidon gather to gripe about Zeus’ temporary support for the Trojans. Athena delivers a grand speech about overthrowing the tyranny of her father. Plans are hatched, pledges of mutual support are given, multiple Olympians are on board, Zeus will be taken down a peg… Right up until Zeus cocks an eyebrow, and then the grumbling stops and everyone begs for forgiveness. The gods are frequent battlefield participants in the Trojan War, but is there really any courage on display when Ares, Artemis, and Apollo join the Trojan ranks and slaughter Greeks? Are Athena, Hera, or Poseidon any better when joining the Achaeans on the plains of Troy? Is it admirable or impressive in any way for an immortal to strike down or punish a human? Is it divine prerogative or abuse of power?

I think there’s reason to believe Homer had more than just comic relief in mind when he developed the character of his gods the way he did.

When we contrast the behaviors of the Olympians with the actions of mortals engaged in conflict in the Iliad the distinction becomes more clear. There are several detailed, graphic skirmishes in the Iliad over the body of a fallen comrade. As wasteful as it may sound, many men die to make sure the bodies of Sarpedon and Patroclus aren’t taken by the enemy and desecrated. These mortals make a choice to uphold a value and they pay the ultimate price. One of the turning points of the Iliad is the death of Patroclus, Achilles’ best friend. Like all the Myrmidon’s under Achilles, Patroclus had held back from combat for days, but after witnessing the injuries and suffering of the entire army in Achilles’ absence Patroclus begs to return and help the cause. Achilles relents, and Patroclus is magnificent, but meets his end under the walls of Troy. His compassion, his loyalty to the bonds of brotherhood, the courage to face Hector of the flashing helmet who had been unstoppable for days are all choices that tell us what type of person Patroclus meant to be.

There’s a touching scene in Book 6 when Hector takes a moment with his wife Andromache and his newborn son Astyanax when he is clearly torn between his belief that Troy will fall, and his family will be destroyed as a result of the war, and his duty to the city as prince and heir to the throne. He holds the contradiction of believing he will die in battle against a hope his son will grow up to fulfill his namesake role as “overlord of the city”. He is clearly conscious of the potential disaster that awaits him, his family, and city. He has many brothers, some of whom spend their days not on the battlefield, but making merry within the palace. He has a choice of what to do with his time and life. He chooses to lead his army from the front and go headlong into battle. He breaks down the gates of the Achaean fortifications, he is the first atop a Greek ship attempting to set it aflame. Homer constructs complex characters, and Hector does dastardly deeds, and makes mistakes on the field of battle. He is part of the tense struggle to bring Patroclus’ corpse back to Troy as a prize of war. Despite this he begs Achilles to not do the same to him. Headlong Hector of the flashing helmet, breaker of horses, is a brave mortal, but imperfect and his choices and intentions reveal who he really is.

Offering mercy or a moment of reprieve to an enemy while engaged in mortal combat is inherently risky, yet human characters do this multiple times in The Iliad. Glaucus and Diomedes even exchange armor after learning their families are linked through a historical guest/ host relationship.

When we contrast these acts with the general flakiness of the Olympians the virtues of kindness, compassion, and courage are magnified. The graphic violence and ostensible origins of the conflict may or may not inspire the modern reader, but the contrast between mortals courageously and loyally defending their friends’ lives and bodies, and generously granting their enemies moments of detent in the shadows of their own deaths is worthy of admiration. Is Ajax worth remembering because he can lift and throw a huge boulder, or because he does so in defense of his friends while many around him flee for their lives leaving him nearly surrounded by the enemy? When Hermes leads Priam into Achilles’ camp to retrieve the body of Hector he risks nothing and can disappear at a moment’s notice, but Priam risks everything when begging for mercy from the man who killed his son.

The immortal Olympian gods as depicted in The Iliad may not be worthy of emulation, but they serve as an effective contrast to the determination of the dying ones. Everyone is good for something, even if it’s just as an example of what not to do. I suspect I’ve ground this point into the dust, but I think it bears repeating. The reason I think it is important that Achilles is not invulnerable, and doesn’t even believe himself to be so, is that one of the assumed truths of The Iliad is that humans are mortal, and therefore the choices we make in our lives, for what purposes and values we sacrifice the finite resource that is our life, are meaningful not only because of the outcomes of those choices, but because they represent our goals, our intent, who we mean to be.

In my next essay we’ll talk about some of the values that influence the logic of these decisions in Homeric epic, but obviously I think this insight is profound and important not only to this poem, but to our lives. People find sources of meaning, goals, and purpose in many different ways. There are some who claim that considering the chaotic swirl of the cosmos, absent divine creation, that human life would be meaningless. Obviously I believe otherwise.

In the context of the tales we tell about immortals, humans occupy an interesting place. The gods are immortal and conscious of the reality of death, but don’t experience it. Animals by and large don’t show much evidence of comprehending or anticipating death even though they experience it. Elephants and some other primates demonstrate evidence of mourning the dead to a degree, but there isn’t clear evidence they are conscious of it and anticipate it in life. Humans both experience and are consciously aware of death and know that it will come for us eventually. After the death of Patroclus, Zeus offers his assessment on the position humans occupy “of all creatures that live and move upon the earth there is none so pitiable as he is” 17:428 Focusing on the inevitability of death is depressing to some, but I’m not certain it need be. Accepting the reality of a situation can also focus the mind’s creative powers. The fact is that you are here, alive in the 21st century, and conscious of it. Regardless of your other beliefs, your time on this planet is limited and your choices matter. The goals we pursue, how and with whom we choose to build relationships, the life and world we attempt to build all speak to who we intend to be and are therefore intrinsically meaningful. The tales of the Olympians juxtaposed against the wonderful ever-changing complexity of humanity urge us to never abdicate the power of that reality.

4000 words. Nice.