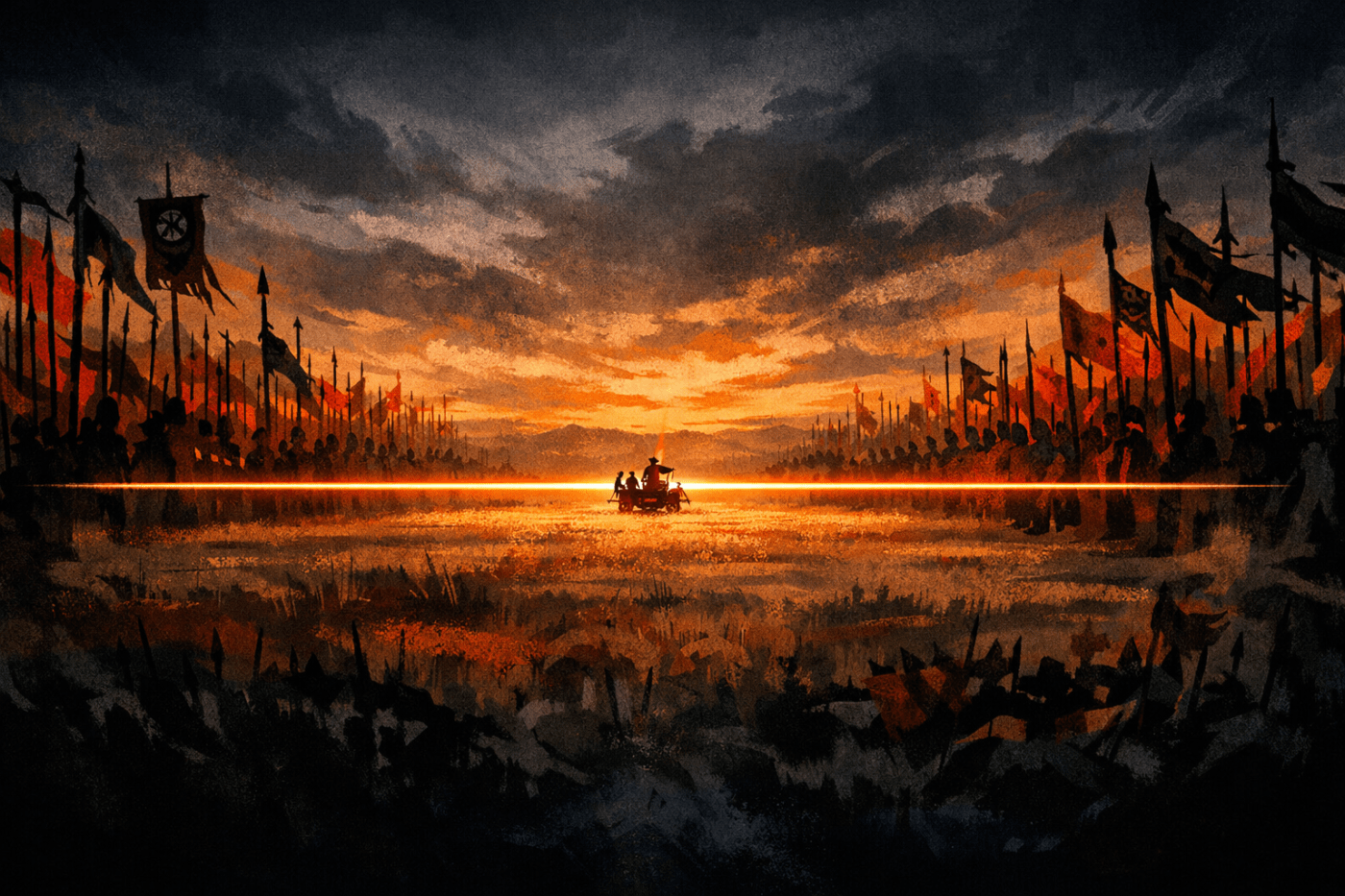

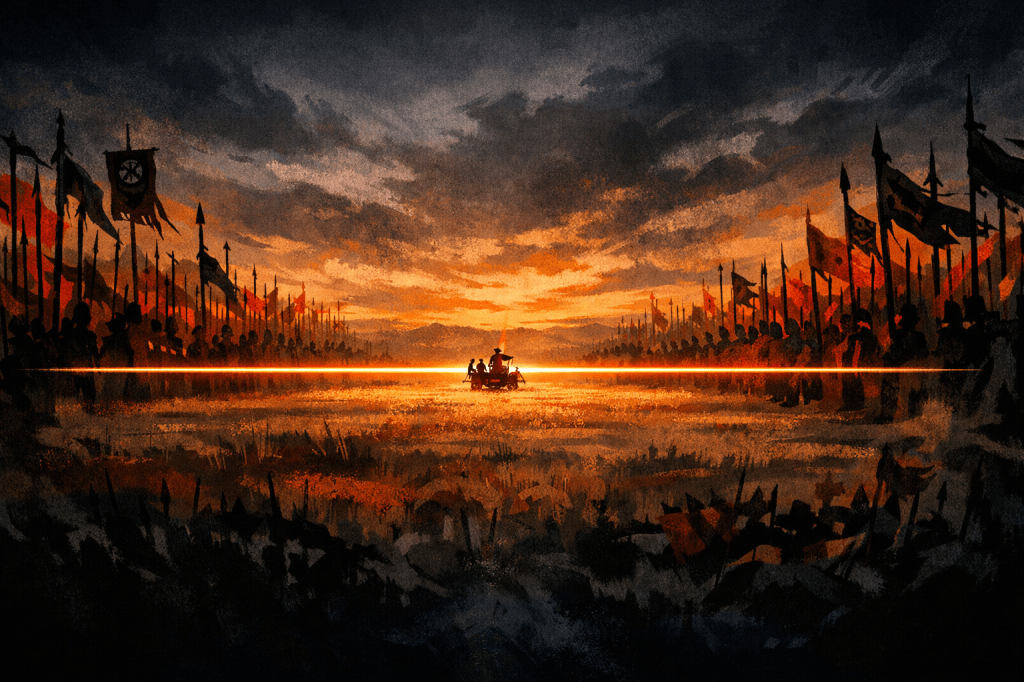

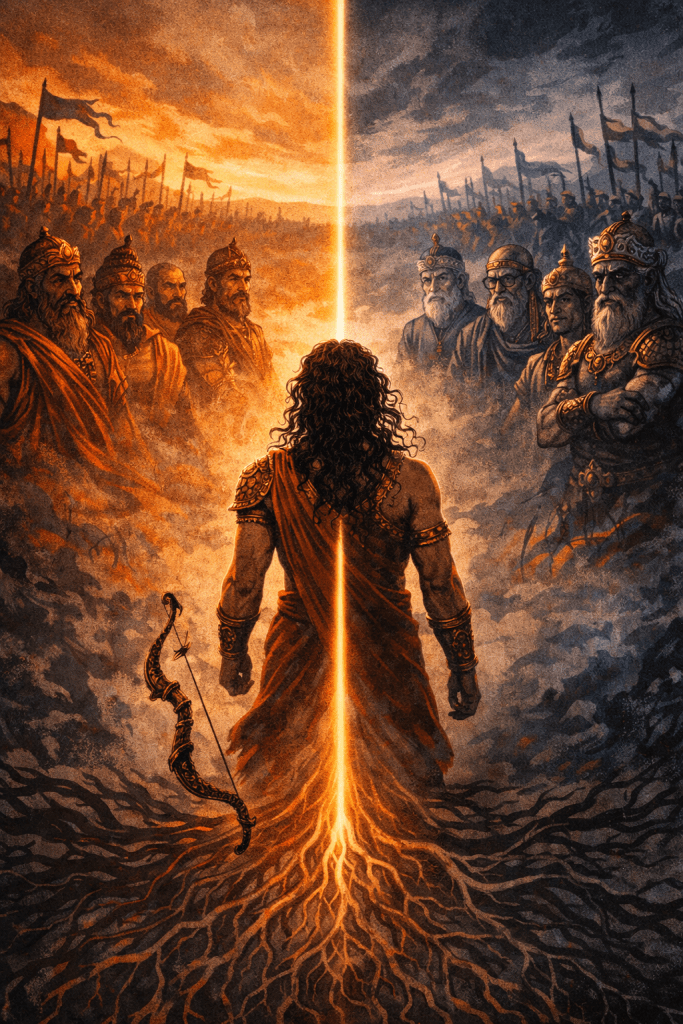

One afternoon in ancient India two armies gathered across a field near Kurukshetra. Following a series of horn blasts innumerable hosts stand in formation with standards raised and weapons drawn. The tension is palpable, yet the battle will not begin until the leader of the smaller force calls to attack. He is absent from the line. Instead he and his charioteer are stationed in the middle of the battlefield locked in debate.

Arjuna, the smaller army’s commander and one of five brothers known as the Pandavas, expresses doubts about the potential devastation and cultural upheaval that would follow a war, even a victory in as righteous a cause as his own.

“Arjuna saw them standing there: fathers, grandfathers, teachers, uncles, brothers, sons, grandsons, fathers-in-law, and friends, kinsmen on both sides, each side arrayed against the other. In despair, overwhelmed with pity, he said: “As I see my own kinsmen, gathered here, eager to fight, my legs weaken, my mouth dries, my body trembles, my hair stands on end, my skin burns, the bow Gandiva drops from my hand, I am beside myself, my mind reels. I see evil omens, Krishna; no good can come from killing my own kinsmen in battle. I have no desire for victory or for the pleasures of kingship. What good is kingship, or happiness, or life itself, when those for whose sake we desire them—teachers, fathers, sons, grandfathers, uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law, and other kinsmen—stand here in battle ranks, ready to give up their fortunes and their lives?” (1:27-34)

On the one hand Arjuna and his brothers have been relentlessly oppressed by their cousin Duryodhana and he has left them with no other recourse. To have any hope of peace in their lives they must fight and defeat him and his allies. On the other hand because of some complicated dynastic history and politics the Pandavas grew up in the same household as Duryodhana and many of his allies are their associates, friends, and teachers. His land is their land, his people are their people. Civil war is far more devastating than external conflicts. The lives that will be disrupted if Arjuna is victorious are the exact lives he would willingly defend against oppression.

Though they want to kill me, I have no desire to kill them, not even for the kingship of the three worlds, let alone for that of the earth. What joy would we have in killing Dhritarashtra’s (Arjuna’s uncle and Duryodhana’s father) men? Evil will cling to us if we kill them, even though they are the aggressors. And it would be unworthy of us to kill our own kinsmen. How could we be happy if we did? (1:35-37)

Fortunately Arjuna’s charioteer Krishna is no mere mortal. Krishna is the eighth avatar of Vishnu the Hindu god of preservation and duty. For those of you keeping score at home Rama was the seventh avatar and the man we know as the Buddha is often considered the ninth. One of the fundamental assumptions of religion is that the divine, whatever it may be, wields power and authority that supersedes human capacity and comprehension, so having a direct line to a deity when faced with an existential moral conundrum is convenient to say the least.

Krishna does NOT hold back. The Bhagavad Gita (henceforth referred to here as “The Gita” to save keystrokes) purports to be the record of this conversation. It has inspired Hindus for hundreds (maybe thousands) of years, and been appreciated by a broader audience for over a century.

The Gita in modern social/political discourse

The transcendentalists found The Gita’s message appealing. Ralph Waldo Emerson described an experience with it thus, “I owed a magnificent day to the Bhagavad Gita. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.” His poem Brahma is clearly inspired by the text.

One American thinker heavily influenced by Emerson was Henry David Thoreau who famously tried living without the comforts of “modern” life at Walden pond. He took some reading material with him, “In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial”. He also famously espoused non-violent civil disobedience as a pathway to social change.

Mahatma Gandhi described his relationship with The Gita in familial terms, “Gita is not only my Bible or my Koran, it is my mother…my ETERNAL MOTHER”. Gandhi cited the Gita’s influence on his adoption a simple lifestyle, eschewing modern comforts, and leadership of an extended campaign of non-violent resistance resulting in dramatic social change.

November 19, 1950 Martin Luther King Jr attended a lecture presented by Mordecai Johnson, President of Howard University, who was in turn inspired by Gandhi’s philosophy of satyagraha and non-violence as a means of social change. Dr. King famously went on to organize and inspire generations of Americans which has affected significant social change including the Civil Rights (1964) and Voting Rights (1965) Acts.

Based on these examples of how the Gita has influenced the modern world one might reason that Krishna’s response to Arjuna was to abandon the battlefield and renounce violence. You know by the fact that I wrote that sentence, such an assumption is incorrect.

What is going on here? How exactly does one take a text about a family feud turned civil war and develop a philosophy of non-violence? Why do folks from such varied circumstances attribute so much to this text?

These are the questions I hope to address in this series, but first I think the reader deserves more information about The Gita and its cultural, historical, religious, and literary context. That information will occupy the remainder of this essay. The reader should also be aware that like any other holy book The Bhagavad Gita can and has been interpreted in a variety of ways and readers have reached divergent conclusions about its meaning and message. We’ll consider one of those in my next journal before I FINALLY get to my understanding of The Gita in the third and final essay of this series. I’ll try to keep the whole thing under 20,000 words. On this final count, I will fail.

The Great Tale of India

The Gita is often presented as a stand alone text. This is how I first encountered it. However it is part of a much larger work called The Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is a Sanskrit heroic epic of post-Vedic Hinduism. As it features a theophany featuring Vishnu it falls within the Vaishnavism tradition. In those respects it is similar to The Ramayana. It appears to have been compiled from oral tradition (as these things generally are) in the ballpark of 4th-3rd centuries BCE. The Mahabharata is somewhat newer than the Ramayana (7th century BCE) and makes occasional reference to characters and events of the older epic. It is a bit longer. In my last series I admitted that I didn’t read a literal translation of the Ramayana because those tend to be multi-volume affairs that run to about 1500 pages and I wasn’t THAT committed to the text when I started the project. The Mahabharata is composed of 18 Parvas (chapters/books) of roughly 100,000 2-line couplet verses. To give you a feel for what that means, the typical description of the length of the text is “10x the combined length of the Iliad and Odyssey”. Something like 7000 pages. That’s a lot of pages. Almost every complete English translation has been the work of multiple translators because people keep dying before the job is done. Several multi-person academic projects are ongoing (NYU and U Chicago), but the apparently dauntless Indian economist Bibek Debroy (He of the 1400 page 3 volume translation of the Ramayana) produced a 10 volume translation by himself. In yet another similarity to The Ramayana, I opted out of reading the entire Mahabharata. I did make it through the RK Narayan’s retelling and found his Mahabharata more enjoyable than his Ramayana (which I enjoyed very much). William Buck’s retelling had the opposite effect. I enjoyed his Ramayana more than his Mahabharata (but it was also a fine read). I suspect this may be due to the fact that there is just so much material in the Mahabharata. The cast of characters is substantial and there are a LOT of subplots. I get the feeling that basically any story that could be grafted into the main plot was. Anyone looking to abridge the story must choose which details to include and which to leave out. Removing details will certainly have unexpected domino effects on how the resulting version hangs together or speaks to the audience. Editing is difficult and choices have consequences. That’s why my essays are so damn long (winking emoji). Consequently I will present a bare bones summary.

Origin of the War

For a compelling dynastic conflict to arise you need a position of power and competing claimants to the throne, and ideally the competitors have some form of legitimacy (heredity, divine or popular mandate). The conflict in the Mahabharata concerns the kingdom of Hastinapura. A man named Shantanu enjoys a relationship with a woman who turns out to be Ganga the river goddess embodied by the Ganges. There’s some marital strife centered on the goddess drowning their children (she has her reasons) and they go their separate ways. A tale strikingly similar to the relationship between Peleus and Thetis that gave rise to Achilles. Shantanu raises their one surviving son whose name is Bhishma.

Shantanu remarries and has two more sons Chitranganda and Vichitravirya. In a surprising gesture of goodwill and brotherly affection Bhishma abdicates his claim to the throne in favor of his younger half brothers and he lives a celibate life to prevent future strife. He ends up living for a very long time. He is at the battle of Kurukshetra. His actions are generally honorable, wise, and consistent with maintaining stability and order within the royal family.

As fate would have it Bhishma’s half brothers both die without heirs. It turns out their mother had another son, Vyasa, from a previous marriage and she presents him as a potential surrogate father to help Vichitravirya’s surviving wives bear children. These children would have a claim to the throne despite not having any direct genetic relationship with dynasty’s patriarch Shantanu. Levirate Marriage: the business of standing in for a dead brother has cross-cultural precedent in the ancient world see: Deuteronomy 25:5-10, Matthew 22, Mark 12. Bhishma and the kingdom accept this plan and Vyasa’s heirs. Vyasa is also traditionally regarded as the original composer of The Mahabharata. Two potential heirs are produced in this way: Dritararastha and Pandu. Dritararastha is older, but is born blind; he is initially accepted, but then rejected as king at his coronation. There may have been some priestly shenanigans involved in this rejection. Perhaps an origin of resentment and distrust for future generations? His brother Pandu becomes king. Pandu marries but carries a curse that if he engages in sexual intercourse he will die. However, Pandu’s first wife Kunti has the impressive ability to get to “know” any god she desires. These interactions produce three sons. Yudishthira is the son of the god of justice, Bhima is the son of the wind, and Arjuna is the son of Indra the sky god of war. Kunti teaches her ability to her sister wife Madri who subsequently gives birth to twins Nakula and Sahadeva via an encounter with the Ashwini the twin gods of science and healing (like twin gods Apollo and Artemis). These five sons: Yudishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva are known as the Pandava brothers or Pandavas and are the protagonists of The Mahabharata. You’ll recall Arjuna, son of the god of war, is the one conversing in his chariot with Krishna prior to the battle at Kurukshetra.

As heirs to the throne you may assume the conflict at Kurukshetra involves infighting among the Pandavas. You would be wrong. They stick together through myriad adversities. As their parentage suggests they develop contrasting personalities.

Yudishthira, son of justice, is generally level headed and preoccupied with doing the right thing regardless of personal cost. He gives Captain America/ Leonardo/ paladin vibes. Bhima, son of the wind, is a bit more impulsive and easygoing, but can overwhelm with force under the right conditions. Very much in the vein of The Hulk or Michelangelo, and in DnD he would fit the Barbarian class. Arjuna, son of thunder / war, is unsurprisingly similar to Thor or Tony Stark. He’s not as dark or moody as Raphael or Wolverine, and definitely Fighter/Ranger class. The twins are not well developed in the versions I’ve read. Sticking with the Avenger analogy: maybe Black Widow and Hawkeye?

Meanwhile Dritarastha has “100” sons, The Kauravas, the oldest of whom is Duryodhana who is the architect of the events leading to the battle at Kurukshetra, and his claim to the throne is not without merit. Pandu succumbs to temptation and engages in sexual intercourse and dies when the Pandavas are very young. The crown passes back to Dritrarastha, but there is pressure for the throne to stay in the Pandava line and fall to Yudishthira following Dritarashtha’s regency. However, it’s easy to understand why Duryodhana would see himself as the rightful heir: his father was the older of the two brothers and is the one ruling the kingdom as the boys reach maturity. Thus we have the makings of a dynastic succession conflict.

If Yudishthira is the heir apparent, then all the Pandavas stand between Duryodhana and kingship. This provides ample reason for him to perceive them as rivals and adversaries. Beyond individual ambition, for a claimant to have any real chance of success at gaining power, there must also be a faction that supports the claim. Duryodhana appears to have this going for him because some of the local aristocracy support him throughout the story. His forces at Kurukshetra are greater in number than the Pandavas. Also, despite questioning his judgment and actions as he pursues a policy of deception, oppression, and even attempted murder against the Pandavas, many of his courtesans, advisors, and elders support him. For example both his father and great uncle Bhishma feel compelled to support Duryodhana in battle despite the fact they recognize some of his actions are unjust. Bottom line: there seems to be a genuine divide on the question of legitimate claim to power between the Pandavas and Kauravas. Like all good conflicts there are multiple layers to the animosity.

Sometimes its Personal

Because Pandu dies while they’re young, The Pandavas are raised alongside their cousins in the royal palace receiving the same education and training. It turns out The Pandavas are the best at everything. There’s an episode that reads kind of like a graduation/ coming out party for their military skills. Duryodhana and his siblings come out and impress the crowd. That is until the Pandavas do their thing. Everyone goes wild. There’s nearly a fight right on the parade grounds when a stranger (who is secretly a half-brother to the Pandavas) comes out and one-ups them and Duryodhana immediately adopts him as a brother and encourages him (He has a name and it is Karna) to challenge the Pandavas to a fight to rule the kingdom. The episode sets up later conflicts and serves as a prime example of Duryodhana’s jealousy that his cousins are so talented and beloved. The versions I have give hints, so it may be better developed in full versions, but the Pandavas may enjoy a few too many jokes at Duryodhana’s expense and enjoy them a bit too much. There’s a comical scene involving a highly polished floor and a fish pond at the Pandava’s palace. Petty jealousy and/or insecurity are common comprehensible motivations for doing ill to one’s rivals so maybe Duryodhana’s villainy isn’t just about power; it may in fact be personal. Regardless, his animus against the Pandavas is the primary driver of the decades long conflict which results in civil war at Kurukshetra.

After the kerfuffle at the demonstration of martial skills that prompts Karna’s adoption, the division regarding succession in the kingdom becomes more public and Dhritarashtra decides it’s best the Pandavas leave town for a while to let things cool down. They relocate to Varanavata. Duryodhana hires a man to build a house secretly composed of highly flammable materials for the Pandavas to live in while there. The plan is to burn the house while his rivals are asleep inside. They catch wind of the plot and dig a tunnel which allows them to escape. The Count of Monte Cristo and Andy Dufresne would be so impressed. Attempted Murder is now on the Pandavas’ list of grievances. Since there’s a target on their backs they decide to live in disguise and not to return home immediately.

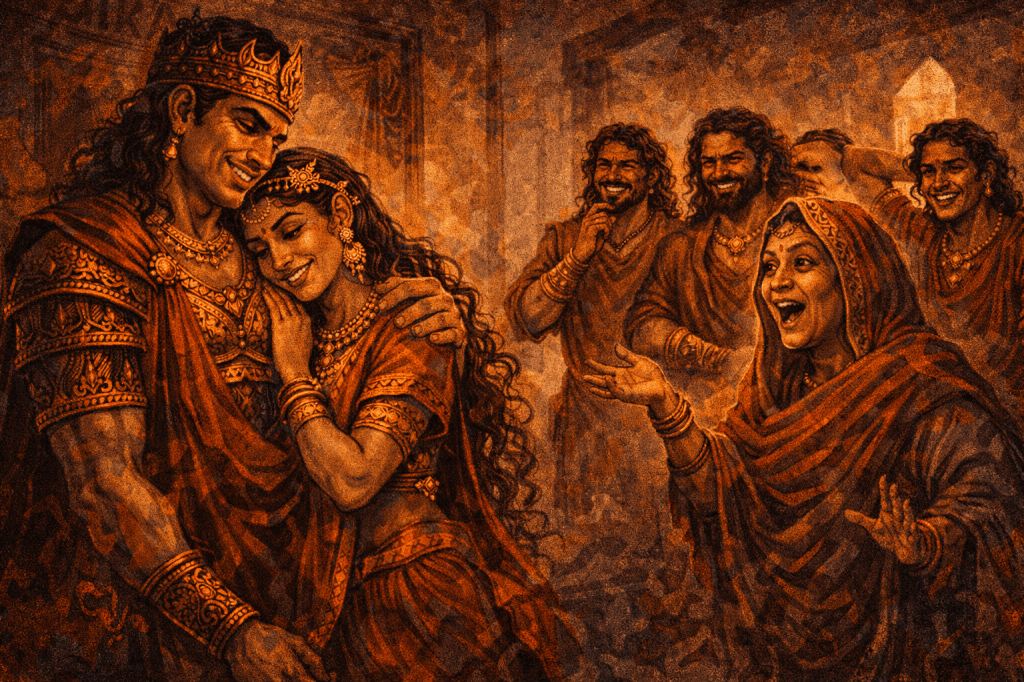

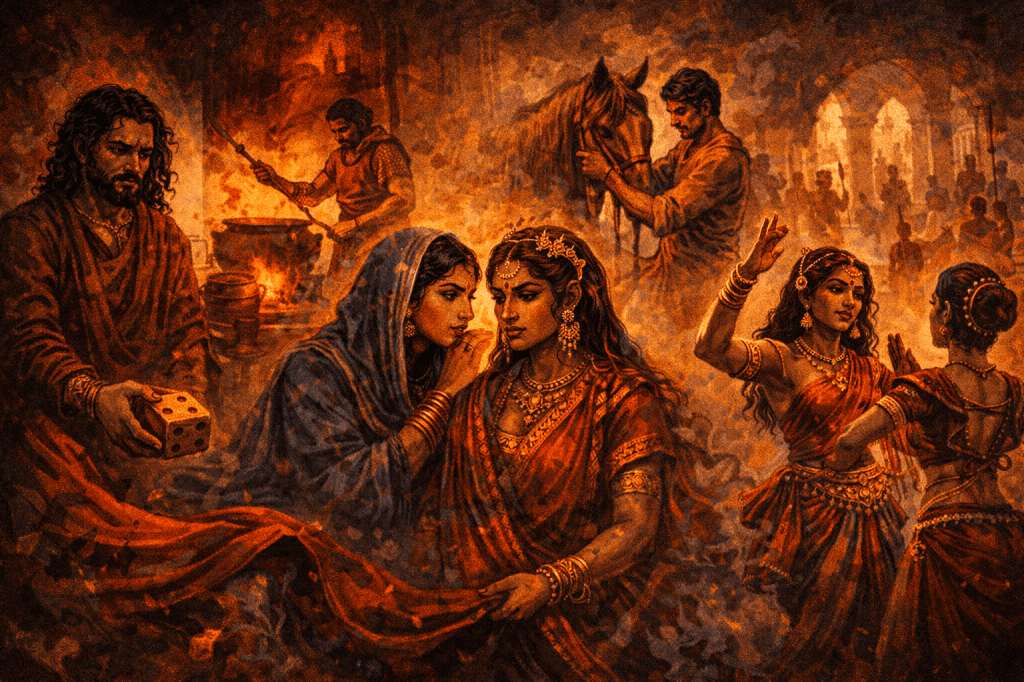

While the Pandavas are laying low they find out a beautiful woman, Draupadi, is hosting her swayamvara (contest to win her hand in marriage). The brothers decide to check it out. To win the fair lady’s hand, as is the case with alarming frequency in ancient epics, one must win an archery contest. See: The Odyssey, The Ramayana, and Disney’s Robin Hood cartoon. Arjuna decides that since any and all are welcome to try their hand in the contest, that even lacking his princely entourage he wants to give it a go. He wins and his new bride accepts him even in his beggar’s garb. In a farcical scene, when he brings his new bride back to the family hideout his mother hears that Arjuna has brought a prize back from the archery contest and without knowing what or who it is she insists that the boys share it equally. Draupadi takes a look at the five brothers and agrees and everyone just kinda shrugs and says, “I guess mom knows best?‽!”, the laugh track sounds and Draupadi marries all 5 brothers.

Raising the Stakes

It turns out Arjuna’s disguise didn’t mask his obvious talent, and when it’s announced Draupadi married 5 brothers the jig is up and everyone knows the Pandavas are alive and Dhritarastha invites them home. The tension between the Kauravas and Pandavas remains. Dhritarastha stumbles upon a new solution. Divide the kingdom. He offers Yudhisthira (the oldest Pandava and presumptive heir) a portion of the kingdom called Khandavaprastha. Yudhisthira accepts and the boys depart for their new home. It turns out Khandavaprastha is either an uncivilized jungle or desert wasteland depending on which version you read. Either way it isn’t a desirable or promising place. As one would expect The Pandavas successfully transform their kingdom into an economic powerhouse and their capital Indraprastha becomes a hub for trade which draws people and business away from Hatinaspura and their wealth is displayed in marvelous public works and a stunning palace. The edifice is so flawless and well maintained that when their cousins come to visit Duryodhana mistakes a floor for the glassy surface of a pool and the Pandavas have a chuckle at his expense. Another brick in the wall.

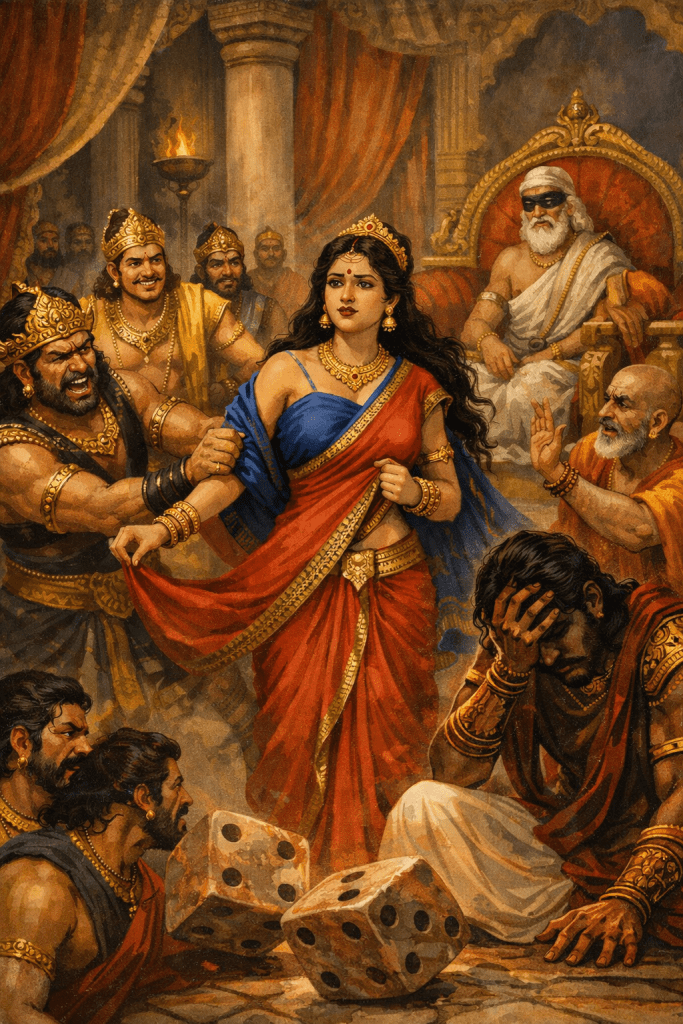

Not to be outdone the Kauravas build their own bigger, better palace and invite The Pandavas to visit. Here we learn of Yudhisthira’s feet of clay. Duryodhana challenges him to a game of dice. The dice are loaded and Yudhisthira goes on a losing streak of epic proportions. He gambles away all his property and wealth, and goes so far as to land himself, his brothers, and their wife Draupadi in servitude to the Kauravas. In a gesture of good will Dritirarastha forgives the debt and all is restored. However Duryodhana immediately challenges him again and the exact same thing happens. This time Duryodhana will not be denied and there’s a scene where Draupadi is humiliated and publicly stripped of her fine clothing to mark her as a servant. Led by an in-law of the Pandavas named Krishna, the assembled aristocracy erupts in revolt.

Before violence ensues a compromise is struck. The Pandavas will go into exile for 14 years. They are free to roam for the first 13, but they must keep their identities hidden during the 14th year. If they’re recognized the exile is extended another 13 years. I don’t know the significance of a 14 year exile in Hinduism, but readers may recollect that Rama was also exiled for 14 years.

Tensions Boil Over

The Pandavas accept. There are plenty of adventures in the forest. Duryodhana constantly has spies keeping tabs on the Pandavas and attempts to kill them far from public view on at least one occasion. At the beginning of their 14th year in exile The Pandavas decide to become servants in the house of Virata, king of Matsya. Yudhisthira adopts the disguise of a wandering brahmana sage who is, and I must emphasize that I am not making this up, an expert at dice. Bhima takes a job as a cook. Draupadi takes a role as lady-in-waiting to the queen. The twins Nakula and Sahadeva manage the royal horses and cattle respectively. Arjuna becomes, to my knowledge, the first transgendered superhero in history. He magically becomes a eunuch who dresses in women’s clothes and becomes the royal dance instructor to the king’s daughter Uttarah. It brings to mind Achilles being stashed by his mother amongst the king’s daughters on Skyros prior to the Trojan War. King Vitara seems to not notice that 6 incredibly talented strangers just happen to show up at his palace on the same day. I guess you don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.

Of course things go swimmingly until the very end of the year. There’s a rapid sequence of King Vitara’s military advisor trying to take Draupadi to be his wife against her will, Bhima killing said military advisor, and Duryodhana hearing about the death of King Vitara’s advisor and mounting a raid to steal all of his cattle. The bottom line is that Arjuna’s identity is revealed when he rises in defense of Vitara’s cattle against Duryodhana’s raid. Duryodhana claims that Arjuna is recognized prior to the end of the exile and the Pandavas cannot return home for another 13 years. The Pandavas and their supporters disagree. Leap years and daylight savings may have something to do with it. Krishna is dispatched to negotiate their return, but cannot broker a compromise. One suspects he didn’t try too hard as he openly despises Duryodhana. That failure to communicate leads to the assembled armies at Kurukshetra and Arjuna standing with Krishna mid-battlefield wondering what he should do.

He and his siblings have been antagonized for decades. All they want is to be left alone to manage their own affairs, yet Duryodhana will not rest until their potential influence has been eliminated, preferably through their deaths. In reality there is no path forward that does not involve conflict with Duryodhana. However, on the opposite side of the battle are their cousins, Drona their teacher, Bhishma their “grandfather”, Karna the half-brother they don’t know they have, and who knows how many other friends and acquaintances caught up in the whirlwind of court politics that bind them to Duryodhana. We’ll dive into the arguments presented in favor of fighting by Krishna in The Gita in the next journal, but we should finish out the narrative here first.

Arjuna fights. After an 18 day battle of traditional and mantra-aided supernatural combat the Pandavas emerge triumphant. They rule in Hastinapura for 36 years. Once a successor has been identified they depart on a pilgrimage to the Himalayas. With the exception of Yudhisthira, the other brothers and Draupadi each die on the journey due to some imperfection of character (Charlie and The Chocolate Factory vibes). Yudhisthira is told that he succeeds because he genuinely tried to pursue a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

That’s the story as I understand it.

As far as cultural, historical, and religious context I will not bore the reader by rehashing my discussion of the Aryan migration, Vedic religion, the Axial Age, and henotheism. If these concepts are unfamiliar Google exists, or the reader can avail themselves of my first essay on The Ramayana here (embed link here).

While some suggest the oral tradition of the Mahabharata goes back several thousands of years, the written text seems to have been consolidated in the 4th-3rd centuries BCE. The Gita is thought to have been composed in the 1st century BCE. How we “know” these dates is beyond me, but assuming they approximate reality to some degree, The Gita would be what is known as an interpolation, or addition to the text not included by the “original” author(s). I’ll resist the temptation to digress into a discussion about what “original” means in an ancient text derived from an oral tradition. Bottom line: The Gita appears to have not been included in the oldest versions of the Mahabharata. Does this mean that its ideas are newer than the oldest texts? Does it reflect a shift in cultural/ religious ideas? If so, what prompted its inclusion?

The Gita occasionally offers open critique of traditional Vedantic Hinduism. It’s not a rejection, but a reframing of the principles of who, what, why and how consistent with Axial Age religious and philosophical transitions observed worldwide. Krishna critiques what one would assume to be perceived limitations and deficiencies of Vedantic religion as practiced at the time and even presents the teachings of The Gita as a restoration of lost understanding.

“I declared this imperishable yoga to Vivasvat, god of the sun, and he told it to Manu, the first human, who told it to his son Ikshvaku. Scorcher of the Enemy (Arjuna), through man an age, the royal sages knew this yoga, obtained as it was through lineage; and then this yoga was lost to the world. Today I tell this ancient yoga to you, since you are devoted to me, and since you are my friend. This is indeed the highest mystery” (4:1-3 Patton)

“Foolish ones say that samkhya and yoga are separate ideas, but the pandits don’t. When just one is practised rightly, one finds the fruit of both” (5:4 Patton)

From these and other statements one can see that The Gita accepts traditional practice as a viable path to release, but notes deficiencies for practical application in confronting the challenges of lived experience. Hence the claim that it fits into “The Axial Revolution”.

Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism were all developing and changing during this time, and all espouse doctrines of non-violence. Could it be that The Gita presents a justification for specific forms of violence in order to contrast against other competing beliefs? Arjuna presents a cogent argument against engaging in the battle because killing friends, family, and neighbors is socially, morally, religiously, and personally reprehensible to him. As I understand it, the rationale for Ahimsa (not harming) is based on the combined effects of karma and reincarnation. Violence or harm is associated with “bad karma” that will keep one in the cyclical realm of suffering and rebirth. There is no exit unless or until one ceases accumulate bad karma. How then does Krishna employ traditional concepts of karma, dharma, ahimsa, sacrifice, reincarnation, and ultimate release to formulate a compelling argument that Arjuna should engage in combat? How is it that arguably its most famous modern interpretations employ its teachings to subvert violence and reach an alternative conclusion? I hope to address both of these questions in my next two essays.