There are a lot of theories about how to define dharma. In a tradition as old and as diverse as Hinduism expecting unity would be unreasonable. The academic analysis is that dharma derives from the Sanskrit root “dhr” which means to uphold or support. Dharma is commonly translated as duty which implies obligation. But what are one’s obligations and duties? What should one uphold or support?

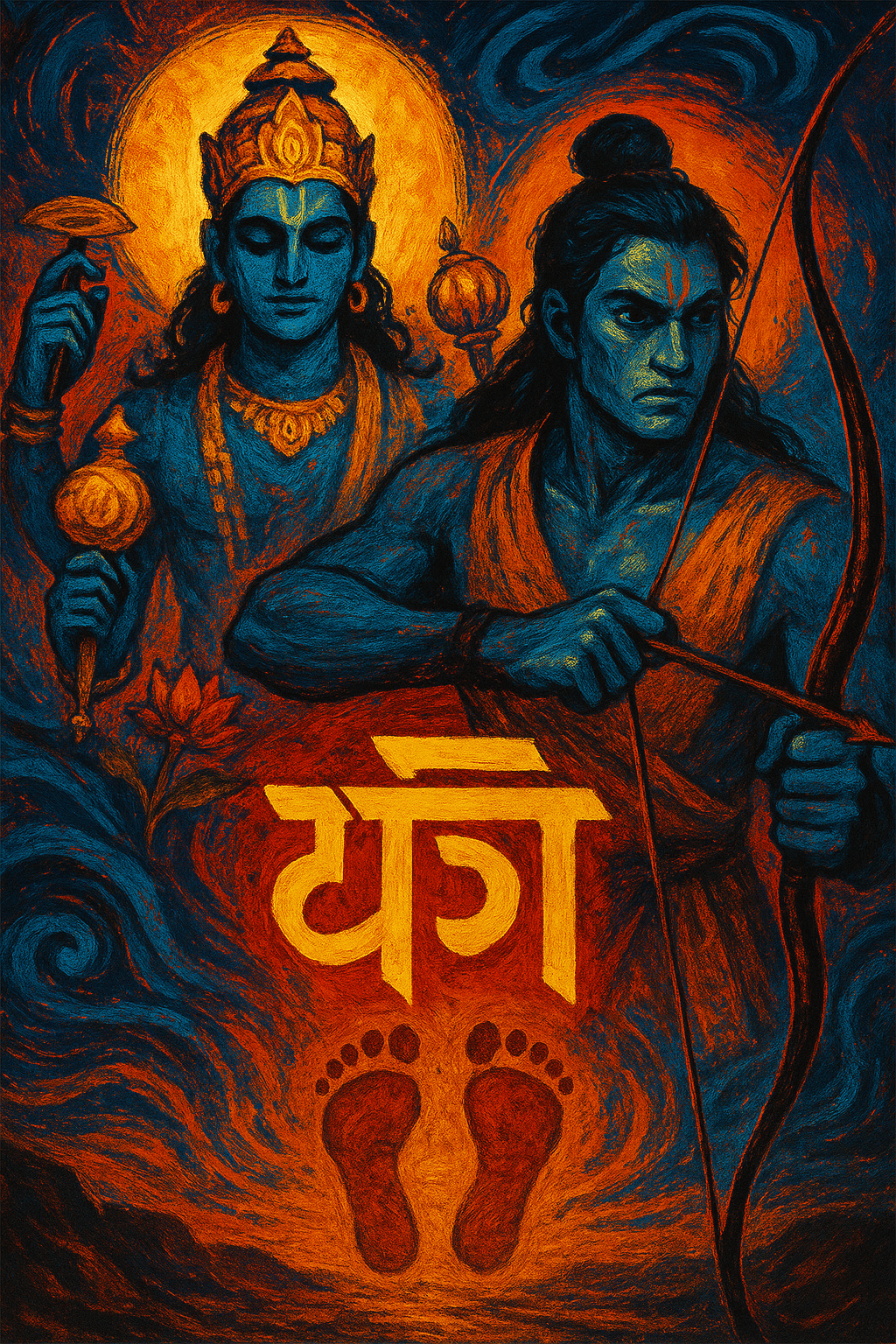

There are many facets of life that compete for our focus and effort, consequently varieties of dharma developed to account for this. There is varṇ āśramā dharma, which reflects one’s duties at specific stages of life. Svadharma, one’s individual or personal duty defined by things like varna, family relationships, occupation etc. Āpad dharma as defined by the presence of adversity. There is even Yuga dharma, which is duties specific to an epoch or age, and thus may change over time. The idea that moral duties are contingent upon circumstance can be a troubling concept. It sounds like moral relativism and appears to contradict the entire post-Platonic philosophical project. I’ve tread this path several times in my writings, so please forgive me if the previous sentence feels like a bit of a repetition. I call ‘em like I see ‘em. I think the Ramayana makes the case for two related approaches that outline dharma in a general sense. The first is that when making decisions one should prioritize values over desired outcomes. It also makes the case that virtues and duties are not absolutes, but are defined by relationships.

In my last journal I tried to make the case that adharma, the opposite of dharma, has many facets, but finds its origins in a desire to possess and control. Definitionally, a focus on principles regardless of outcome seems like a reasonable opposite. What does this look like in The Ramayana?

The most complete presentation of dharma competing directly with adharma occurs when Rama’s circumstances rapidly change from impending coronation to 14 years of exile.

Rama Confronts Competing Concepts of Dharma

When she first learns of his planned coronation, Rama’s stepmother Kaikeyi is joyful, but at the prodding of one of her servants her mind suddenly changes. This interaction is a great illustration of desire and aversion as two sides of the same coin. Fearing loss of status is coupled with the desire for continuity and authority.

The servant warns, “Take the measure of your enemies and destroy them while you can. You can be mistress of the world. Or a slave, take your choice“

We are then told, “Time cast his shadow over her heart… her breathing tightened, and her palms perspired; her soul was dark; her heart pounded and anger pressed his mask over her beautiful face.”

I think the description of the physical manifestations of the queen’s emotional state rings true and highlights an insight. The physiological response when faced with uncertainty is basically the same regardless of the stimulus; the sympathetic nervous system is at work. The text highlights a change in facial expression: one might say she’s ready to “drop bombs”, her palms are sweaty, but it omits weak knees, heavy arms, and mom’s spaghetti on her sweater. I think this connection between desire/aversion, uncertainty, the physical and emotional manifestations of anxiety coupled with the proven utility of mindfulness practices and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat anxiety in the 21st century all suggest that identifying desire as the basis for suffering is accurate.

Relevant to our discussion, her decision to have Rama exiled and her son Bharata placed on the throne are among the most reviled and criticized decisions in the epic. Everyone: the king, her “sister wives”, her stepsons, the assembled nobles, the local citizens, and even Bharata her own son and now future king, all go ballistic. Her actions upend the order of their lives which in turn induces aversion, uncertainty, fear, and anxiety throughout the city. Misery loves company.

After accepting exile Rama goes to his mother’s chambers. Her response displays genuine love and concern for her child, but this love is laced with fear. His mother tells him, “Do what you want, you don’t have to obey him. Stay with me, hide here in my room for fourteen years… Or else I will die, for you are dear to me.” When he resolutely states he will leave she responds, “Kosala is ruined, I am dead, your father’s life and fame are gone, and out of all of us only Kaikeyi and Bharata will be happy. You will fall into hell for killing your mother!” She will not be the last to foretell doom for the city if Rama leaves.

Rama’s brother Laksmana is with him when he accepts exile and accompanies him to his mother’s chambers and there expresses his opinion on the matter, “The king is a slimy old fish that kills his brood. Why allow him to put us all in another’s power? I will just go kill my father, I will not stand this… Brother, leave everything to me. Go on with your business… My hands are for killing”.

Sumantra, the king’s chief military advisor, also encourages Rama to disobey his father, and when he won’t the response is swift and violent, “So! See revealed the poverty of gentleness, that cannot help you who always use it. Rama, be forgiving while it’s peacetime, but when people come against you, you’ll only win by force. Reason must at last resort to power, and compassion is feeble, it is weak, it trembles. What real man meekly bows to Destiny?… You have a man’s form and a woman’s deeds! You’ve spent all your courage. Prince, pay Fate no regard, do not believe in good and evil!”

These all represent highly emotional responses driven by a desire to maintain control and preserve status in the kingdom. Implicit in them is the assumption that our judgments are correct and our actions are compatible with that which we desire. That is to say we assume we can accurately assess the potential risks, benefits, and outcomes of decisions, actions, and events. This amounts to a utilitarian perspective on life. Our behaviors are means to our desired ends. I won’t go into an analysis of Utilitarianism, but I think the frequency and severity of errors in human judgment and the fact that we have all heard of “the law of unintended consequences” suggest it has limited validity as a moral philosophy.

I suspect humans naturally gravitate to a utilitarian approach to life. We inherit the biological imperatives to survive and reproduce (ends) and we use a variety of skills (means) including pattern recognition to inform our decisions and behaviors in the present to increase the probability of those desired outcomes. So we come by it honestly. However, our mental models are flawed, our judgments are biased and often incorrect, and even when these are accurate our ability to execute our vision to achieve a desired outcome is limited. In recent times we have identified specific fast acting neurological pathways which are finely tuned for questions of immediate survival which get us into trouble under other circumstances. It should come as no surprise that cultures throughout the world have adopted strategies to temper the reactivity and other cognitive imperfections that contribute to maladaptive behaviors. The Ramayana does not present a formal argument against utilitarianism, but Rama rejects it and presents a competing vision for how to navigate distressing situations.

He first points out that humans have a limited understanding of the world and our own lives, therefore our judgments are suspect. He wins his mother and brother over by pointing out that the decisions made by the king and their stepmother/ sister wife are not reflective of evil character, but fear, and that they should not fall into the same trap.

“Kaikeyi was always carefree; this deed is nothing like her, and it is truly not her doing to sadden the king. I wait patiently for you to open your eyes and see. No man is always the same. Worry and care waylay us all. Kings will misrule one day and bring justice to all the next. Singers will fall into the pit of helpless misery for no cause, and then may sing their happiest songs. Men may anger against all in the world and from that rage do great kindness and fashion wonders of beauty. People who think they care for nothing at all have saved more lives than they ever knew, yet believe themselves alone and unloved.”

Rama’s Response

During all this palace intrigue and turmoil we are treated to an extended examination of competing dharmas and how one manages conflicting duties. Lakshmana’s claim that “my hands are made for killing” references their membership in the Kshatriya varna. This is generally understood as the warrior and ruling caste, so the assumption that action, specifically violent action, is an appropriate way to navigate conflict is inherent in the discussions between Rama and his companions. How, when faced with an apparent “wrong”, can Rama refuse to use force? It’s his svadharma to act (another great example of this can be found in the Bhagavad Gita). Here in the Ramayana the implication of Rama’s refusal to adopt violence is that other duties supersede this understanding of his caste.

Rama’s conversation with his father makes this understanding explicit. After his father encourages him to refuse exile Rama responds, “Will I disobey you and judge your commands because your motive may be desire? As though it were on a wheel, whatever we see of happiness and sorrow all turns around Fate. Fear and bravery, freedom and bondage, birth and death, love and anger all pivot on Time’s wheel-hub. Wise men may give up long hard training all in an instant, things well-begun may be hindered by unthought-of accidents, all from Time. The Father is the Master. You gave me life. So end Kaikeyi’s alarm and find peace. Drive out bad feelings as you banish me, I will see you free from debt when I return. One must keep promises or not make them.”

To which Dasaratha replies, “I think that is no longer true”.

Rama concludes, “If I disobey you, no other good deed, no wealth, no power will restore my good name. Keep your word and preserve the three worlds, keep us safe. For every broken promise breaks away a little Dharma, and every break of Dharma brings closer the day the worlds too must break apart. If man breaks his word, why should the stars above keep their promises not to fall?”

Rama’s belief does not appear to be that one does good to receive good in return, but that when one does evil the fabric of existence, individual and cosmic, is threatened. This reflects the traditional vedic conception of Dharma as that which upholds and supports the divine order. An important difference being that here Dharma has been extended beyond priestly performance of ritual to individual behavior. Drawing an explicit parallel between the individual with the cosmos is consistent with axial age refinement, “no other good deed will restore MY good name”. The bottom line is that we see a statement that duty and dharma are contingent upon circumstances, specifically relationships to other people, our community (cosmos), and ourselves. Rama also demonstrates that virtues like filial piety and honesty are more important than our agendas or immediate desires.

Rama as Prototype

In Plato’s Republic Socrates makes the case that the best case scenario for government is an enlightened despot, a philosopher king. Monotheistic religions generally posit this same approach. Islam literally means submission, submission to Allah and his will. The Messiah of the Old Testament was expected to rule and reign righteously on the Davidic throne. The Christian belief in a Millennial Messiah in the form of a Resurrected Jesus Christ is expected to do the same. The categorization of Marcus Aurleius as one of the “Five Good Emperors” who ruled at the height of Roman power certainly lends weight to the enduring popularity of his Meditations. The “Apotheosis of Washington” which adorns the ceiling of the US Capitol’s rotunda sends a similar message. The Ramayana lays out a vision for the behavior of an enlightened Kshatriya ruling warrior class. Rama’s refusal to be baited by his brother and the charioteer Sumantra tell us Rama does not lightly adopt violence, but the latter half of the story assures us he can and will employ it with devastating effect. Fans of King Arthur know that a myth of a righteous king who presides over a golden age that inspires and restrains the guys with the money and weapons has a big potential upside for society as a whole and seems to be universally told. Are principles of action, power and leadership compatible with wisdom, morality, and a philosophical approach to life? A timeless question. The tension between these two lifestyles is addressed head-on during the succession crisis.

One of the few people who doesn’t lose his cool when Rama is exiled is his spiritual advisor Vasishtha. In a boarderline comical scene there is an archetypal argument between Sumantra (Kshatriya caste) and Vasishtha (Brahmana caste) about the merits and demerits of Rama’s choices.

Sumantra the charioteer found the priest Vasishtha in the silent street and said, “Brahmana, the world is without support, it is gone to Hell. The old Kshatriya Dharma is vanished forever. (Kids these days… Am I right?) Sorrow will kill the King, shackled to a vile prostitute posing as our Queen.”

Vasishtha said, “Truly I find the world much the same as ever.” (Nothing new under the sun)

Sumantra: “Hear Ayodhya (the city), silent with blame!”

“Let go anger, abandon violence,” said Vasishtha, “Don’t you know anything? Rama is the Sun of the Sun, the fame of fame. He goes with Sita, he goes with victory.”

“Ah no,” said Sumantra, “Clever speakers feign piety to deceive and tell others of Dharma in rich tones, but there was a time…”

“Clever profiteers also feign foreign wars to deceive the simple and all paid liars are not priests,” said Vasishtha. “Traitors make a show of righteousness and holding knives behind their backs they plead for peace. But my place is to calm, to avoid, to soften, to look before walking and take thought before speaking. Men must have laws, sometimes hard to follow, but harder to find once lost. Dasaratha will die, so let him die in peace, for your life must end one day. Give up war’s desires. Throw out fear of fearful things. An hour of separation cannot be avoided…. What is beyond understanding – that is Destiny.”

“Destiny? That is a poor frail thing, where all is lost because a good hour passes and the stars who care nothing for us are not in their right places. Who is Time to turn his back on us? Are we not men?”

“Time is hidden from you, charioteer. You can only see his work, not him”

“I’ll not believe that, brahmana. When I meet a roadblock I break it!”

“Destiny is unthinkable, how can you regret it?” asked Vasishtha.

These guys don’t pull punches. They point out how caste members can abuse their roles and create chaos. Sumantra is a firm believer in actions dictated by goals (when I meet a roadblock I break it), while Vaisihtha believes in acting according to principles (men must have laws) because the consequences are fundamentally unknowable (Time is hidden from you… Destiny is unthinkable). These perspectives are presented as features of these two castes. I’m not a believer in class distinctions, but I will admit that individuals develop dominant personality traits influenced by social/cultural circumstances. I suspect we can all recognize this sort of debate in our own minds when confronting stressors.

In these pages Vasishtha the Brahmana priest and Rama the Kshatriya warrior prince are both accused of adopting passive roles while the kingdom crumbles around them. Are their decisions genuinely reflective of passive fatalism? Is Rama in fact “doing nothing”? It seems to me the remaining 200+ pages of the book serve as a hefty counter argument. He does plenty. He is not paralyzed by uncertainty, he doesn’t dither and overthink, and he is neither helpless nor resigned.

Silencing the Doubters

I think it’s fair to question the assumptions underlying the accusations of neglect. Is the kingdom crumbling? Do these events pose an existential threat? Everyone claims that because Rama, the heir apparent, the golden boy, will not be assuming the throne that the kingdom will fail: “From this day forth will Ayodhya be vacant, her dusty yards unswept, her cattle gone, her flags torn down, her wells dry, her fires dead”.

The fact is the population receives an enormous capital infusion when Rama and Sita divest themselves of their wealth, “The Kosalas came pushing through the street again, crowding their way to Rama’s palace – ‘Throw down your inventions and plows, go see Sita, she gives away riches’”. The risks and benefits of state sponsored wealth redistribution are a longstanding matter of debate, but the consequences of wealth concentration and disparities are generally accepted as having a long term destabilizing force on a community. Without belaboring the argument; the city of Ayodha and the Kosalas are fine in Rama’s absence. The people maintain a sense of unity and their wealth and power are not diminished during Bharata’s regency. When Rama returns Bharata gladly cedes power and the city continues to flourish for thousands of years. It turns out a dozen years without Rama weren’t the end of the world, and because he confronts and defeats Ravana during his exile, Ayodha and her people are safer and more esteemed in the long run. The catastrophic consequences everyone imagined when Rama’s place was usurped failed to materialize.

This is pure speculation on my part, but I don’t think it a stretch to suggest that had Rama abandoned his Dharma and granted the collective wish that he lead a coup against his father he may have set a precedent that could have had devastating long term consequences. I think the history of Rome (The Gracchi Brothers, Sulla, Pompey, and of course Julius Caesar) and the partisan division we currently experience in The United States of America (the abandonment of historic norms, disregard for constitutional and other legal precedents, concentration of power in the executive branch, and dysfunction of the legislative houses engaged in by both major political parties) offer supporting evidence for this concern. The point remains that we generally overestimate our ability to accurately forecast, so abandoning our core principles and values in a moment of anxiety about the future is fraught with peril.

The other accusation hurled at Rama is that he is adopting a passive role and cowardly acquiescing to fate. In a prior essay I tried to make the argument that our cultural understanding of fate and destiny may not match that of the ancient world. Specifically I argued that the message of Oedipus the King was that character, individual beliefs and choices, are intimately intertwined with destiny, not that fate is unavoidable. The notion of “fatalism” as a passive stance in which “nothing can be done to shape the future” may be a philosophical position one could adopt, but that may not be what is implied when Vasishtha and Rama speak of fate and destiny.

To me their words and actions reflect a genuine agnosticism about the future. They know that they do not know. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld the future is full of known unknowns, as well as unknown unknowns. By definition we cannot accurately account for the things about which we are ignorant.

“Have you seen Death’s face? Have you seen Hell that you will talk of it so lightly and use it for your blame?”

“Time is hidden from you, charioteer. You can only see his work, not him”.

“Destiny is unthinkable, how can you regret it?”

I suspect knowing Sanskrit would be helpful here. Rama may make a subtle distinction between whatever terms are translated “Fate” and “Destiny” and if I were a fully invested reader I’d perform a Google search and tell you about the 5 different Sanskrit terms that can be translated as these two words. But I’m not. I will say this. Rama seems to accept that some things are inevitable, “Rust will come to bright things, fire will burn our homes, blight will consume our grain, all these things are sendings from Fate”.

He also knows that actions have consequences; the future may be unknown, but it is malleable.

Discussing his father’s death with his brother Bharata, “Death is at last found to be a part of all life, and never can we escape it, and Death does not change a promise made. At the end of life, when this body is burned, a man takes Brahma’s way if he has lived well; he takes a good way well-wrought by men of the past”.

Rama’s Virtue Ethics

If Rama rejects a utilitarian approach to challenging situations, but he is not a passive plaything of predestination, how does he navigate life? What does he mean when he speaks of Dharma? While not always explicit, he definitely has a code.

I love the exchange between Rama and his brother Bharata when he makes the case, that even though their father died the day he left the city to go into exile, Rama must still honor his commitment for the next fourteen years, “The first betrayal may be easy or it may be hard, but after the first betrayal then the others soon follow. The heart, Bharata… keep note of your heart and don’t stifle it. There lives the soul, clear, never stained, watching all we do or think to do, so let a man be still and find his heart. That is the only safe rescue. What use is a castle or a palace or a great stone fortress that is no defense against Time? Since we have come together, our separation some day is certain. While we are together as two men during this lifetime, let us keep the truth”.

In these statements Rama reiterates to his brother the same message he gave his father and assures us that integrity is his primary value. I personally find the statements, “Since we have come together, our separation some day is certain. While we are together as two men during this lifetime, let us keep the truth” to be inspiring and a great articulation of acceptance without resignation.

We’ve also already seen him exemplify patience and compassion. When he’s called a coward, he assures us he is not emotionless, nor is his acceptance passive. Rather than resort to name calling or retaliatory accusations, Rama calmly offers his point of view and asks folks to assess the situation from a different perspective. When addressing his mother and brother’s anger he actually defends his stepmother who demanded his exile “Kaikeyi was always carefree; this deed is nothing like her, and it is truly not her doing to sadden the King. I wait patiently for you to open your eyes and see”.

Later, after his wife is abducted and missing for nearly a year, after a protracted search and the siege of Lanka, after an intense battle concluding in single combat between Rama and Ravana, one might expect Rama to behave something like Achilles after defeating Hector. This is after all a heroic epic and many have suffered because of one man’s ambition. Bloodthirsty rage and celebrating violent triumph over one’s enemy is how these stories are told. As I discussed in my series on The Iliad, that expectation may reflect our own cultures toxic views of masculinity, but those texts certainly don’t shy away from these narrative features. Rama doesn’t celebrate over the death of his foe. His army doesn’t sack the city. He allows Ravana’s surviving brother to perform funerary rights for him back in Lanka, and actually expresses concern for the innocent pawns in this violent conflict, “Why is it so quiet?… I had not wished harm to your beautiful city; now she is desolate”.

Rama also displays the twin virtues of trust and loyalty. The roots of Sita’s abduction are sewn because Rama is faithful and devoted to his wife in the face of temptation from Ravana’s sister Surpanakha. The interaction between Rama and Surpanakha can be drawn in any number of ways, but Buck’s telling portrays Rama as polite, yet assertive.

Surpanakha said, “I’ll take you to the broad city of Lanka by magic, dear Rama. My brother’s wealth will let us live like a King and Queen.”

Rama smiled at her. “You see – I am already married. To a proud woman like yourself, a co-wife is misery. (I wonder how he reached that conclusion? Someone tell Joseph and Brigham) Don’t think more about it.”

The interaction between the femme fatale and Rama’s brother Laksmana is too funny to leave out. When her gaze shifts from Rama to his brother Laksmana responds with a wry smile, “Don’t take second best.”

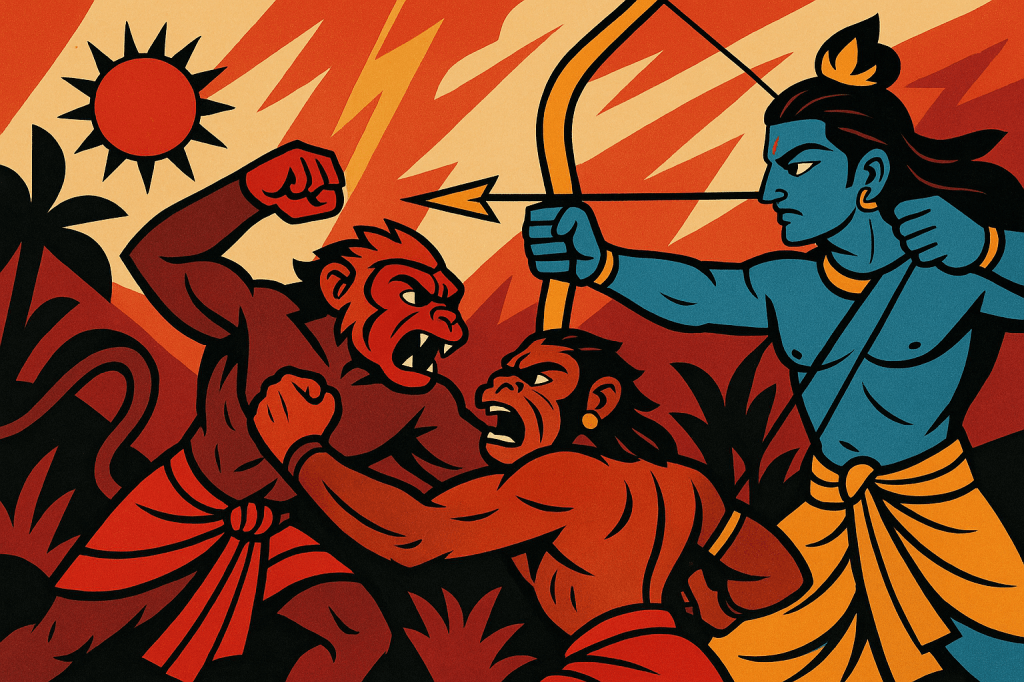

Sita is kidnapped while Rama is away. Laksmana was asked to not leave her side precisely because of the dangers they knew lurked in the forest. Laksmana was put in the impossible situation of honoring this commitment, hearing sounds that gave the impression Rama was in danger, and the demands of a panicked Sita that he go to Rama’s rescue. Ravana abducts Sita as soon as Laksmana is out of sight. I can confidently say that if I was Rama and returned to learn my wife was kidnapped after my brother failed to do what I asked him, I would probably shout, point more than a few fingers, and harbor some resentment. You had one job!… Rama and Laksmana have no such falling out. They remain steadfast companions. Laksmana consoles his brother and Rama delegates significant responsibility to Laksmana for recruiting and leading the search and war efforts. I don’t have time to get into the whole monkey kingdom subplot, but in another situation which demonstrates his ability to engender trust and loyalty, Rama develops pivotal relationships with monkey power players Sugriva, and the spectacularly talented Hanuman.

A striking example of Rama displaying trust and fostering loyalty is his relationship with Ravana’s brother Vibishana. After Vibishana implores Ravana to avoid war and return Sita to Rama he is exiled. Vibishana seeks shelter in Rama’s camp. Understandably Rama’s lieutenants are suspicious of this refugee. Sugriva, the monkey king says, “He came to spy on us and kill us in our sleep”. A common enough wartime strategy.

Rama responds, “I will fight Ravana but not the innocent. Vibishana’s face and gestures and words are open. He has done no wrong. He is not clever or busy. Lowly people who know everything may follow their suspicions, but when someone seeks my refuge he cannot be slain, he will be saved though it will cost my life”.

A relieved and grateful Vibishana appears to quote a verse of something, but I haven’t been able to track down the original, so I can’t be certain, but there seems to be precedent for Rama’s grace.

“Never murder one who is not fighting, Nor a warrior who hides or flees bewildered, Nor any one wounded.

Though he has just now stopped war, Though his cunning hands touch over a proud heart,

His betrayal blocks your Dharma like a frontier barrier, A wall of stones”

Vibishana proves a valuable addition to Rama’s efforts to recover Sita, and remains his ally for thousands of years into the future.

Rama as Enlightened Despot

Earlier I discussed the melding of the spiritual/priestly/teaching class (Brahman) moral perspective with the strength and action oriented ethos of the warrior class (Kshatriya) as presented in a variety of traditions. How exactly does Rama fulfil this role? He refuses to employ his considerable strength and skill in the realms of death and destruction in the service of his own ambition, but does so in the defense of the weak, the disenfranchised, and the captive. He will not seize the throne himself, nor allow his brother, nor the army to install him as king. When is violence an acceptable answer?

In one of the most questionable decisions of the story Rama kills the monkey tyrant Vali from under cover while he is engaged in single combat with his brother Sugriva. Vali had previously unjustly exiled Sugriva, and to add insult to injury, seized his wife. An exiled and deposed ruler whose wife has been stolen and is being held captive? I wonder what could have swayed Rama into taking Sugriva’s side in this conflict?

What about the war against the Rakshasas? Wasn’t he serving his own interests by laying siege to Lanka? There’s certainly support for that perspective. An alternative argument drawn from the text is that violating a woman, especially a married woman, is a high crime worthy of severe punishment. I’m pretty sure there’s a reason Sita’s kidnapping is presaged by Rama’s refusal to succumb to Surpanakha’s offer, and Rama gains the monkey kingdom’s support by helping overthrow a ruler who has taken his brother’s wife as his own.

In addition to defending the sanctity of marriage, the pretext of Rama’s entire existence as an avatar of Vishnu is that the Rakshasas are running amok disrupting the cosmos and peaceful existence of humanity. He is ignorant of this fact, but WE know the deal. Rama’s very first adventure in his youth was hunting Rakshasas. Prior to Sita’s abduction, he gained a greater appreciation of how the Rakshasa plague was affecting those outside the city walls.

One morning during their exile Agastya (forest dwelling hermit/guru) led Rama out onto a spur of the mountains, high on the hillside looking south. Below them the Vindhya Hills ended and the thirsty dry jungles of Dandaka Forest reached out to the south as far as they could see over the land.

“We are far from Lanka,” Said Agastya, “but the edge of Dandaka is the frontier of the Rakshsa kingdom on Earth. For the most part Dandaka is a huge wasteland. It knows no master but Ravana… Ravana the Demon King believes he owns the universe; what are men to him? Pleasures distract him and he scorns men as but his food, weak and worthless.”

Shortly thereafter he meets a tiny race of people, The Valakhilyas, who live in the Dandaka forest and learns of their oppression by the Rakshsas who ask him to “Free this ancient forest, deliver us from the Night-Wanderers”.

Rama replies, “I have strayed from the Dharma of warriors if this has happened while I was near you”.

Sita is uneasy after hearing Rama’s willingness to engage in violence. I get the impression that part of their exile is to adopt the life of pilgrims and seekers and abandon their roles as rulers and warriors and she doesn’t want to falter in this commitment. That may be conjecture on my part, but it seems to be implied when she says, “Do not carry war with you; in Ayodhya once again become a warrior. Don’t let desire make you do wrong, do not kill demons without a cause for war (little did she know) … Do not carry war with you, or by small degrees your mind will alter”.

Rama’s reply reflects his kshatriya varna, but I think it has universal application, “Princess, war is within us, it’s nothing outside. No warrior neglects his weapons. He never gives them up. It is a shame to me that those saints must seek my protection that should be theirs without asking. Sita, a warrior like other men enjoys peace, but misfortune and peril make him flame up in anger and resist”.

The truth is we are all capable of anger, inflamed passions, and violence. Evil exists, and we will encounter it in our lives. This fate is unavoidable. There are a range of responses one can have to this inevitability. Rama seems to embrace a path somewhere between passive resignation, and hot-headed, impulsive reaction to circumstance. We are all familiar with the human ability to rationalize even the most egregious violence and oppression, so the GPS coordinates of the ideal middle path remain seldom trod.

Sita identifies this difficulty when she responds, “How can you tell what is right? You are only doing what you like.”

To which Rama replies, “Dharma leads to happiness, but happiness cannot lead to Dharma.”

This sort of cryptic inverted phrasing is notoriously easy to formulate (insert link to one of my favorite Mystery Men scenes here) so is that happening here? Maybe, but I don’t think so. Allow me a brief digression in which I will approach my main point.

Where I finally get to the point

Let’s step back and consider how it is that we can scale a concept like Dharma all the way from the macro/cosmic level like maintaining structural integrity of the universe, down through the business of supporting the human social order, and finally to these granular personal interactions and the business of fostering the virtues of integrity, patience, compassion, trust, loyalty, and defense of the oppressed? What unifies these wide ranging considerations? What I see is that Dharma is consistently defined by the virtues and behaviors that are centered on maintaining healthy relationships.

One may have a vision for how to make the world a better place. One may see behavior in others that leads to misery and suffering on individual and structural scales. One may “know” how things “should” be, but human experience is littered with cautionary tales against seeking desired ends without regard to the means employed. On the other hand honesty, loyalty, patience, and service, especially when mutually expressed, build and maintain healthy and fulfilling relationships regardless of what life may send our way.

Returning to Rama’s uses of violence. He fulfills his duty as a warrior to the disenfranchised of the pilgrim/forest community. He defends the marriage of the monkey king Sugriva. He protects his wife against unwanted advances of the demon king Ravana. Rama is a great ruler, friend, and husband not because he is violent, but because he employs violence only when appropriate in the context of serving those relationships. I think this claim holds water specifically because he previously refused to take action against his father. Something like “the exception proves the rule” type argument.

With this understanding we can make sense of Rama’s response to Sita. Obeying Dharma, fulfilling duties, building healthy relationships may in fact lead to happiness, but seeking individual happiness while disregarding relationships with family, friends, community, and the cosmos is notoriously perilous. Pursuing Dharma leads to happiness, but pursuing happiness does not lead to Dharma.

Duty and Dharma

I volunteer as a Scoutmaster. The Scout Oath employs the word “duty” as in “On my honor I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country”. Some folks use scouting as a vehicle to inculcate a specific form of pseudo-militaristic “patriotism” and that has always rubbed me the wrong way. In an effort to lead our troop in a way that observes the word and spirit of the Scout Oath in a way that agrees with my conscience I often ask my scouts about how they understand the word duty. I generally get something like, “It’s something you don’t ‘have to do’, but you really should do”. This is similar to how I understood it in the past. I bristle against that sort of vague understanding. The word “should” makes duty into something defined externally which opens it up to abuse and manipulation. Declarations like,“Love it or leave it” and “If you don’t support the war, you don’t support the troops” imply a “duty” to support government policy, dominant cultural norms, and violence regardless of personal conviction. To surrender judgment to a nebulous public opinion strikes me as a perilous abdication of one’s agency. To do so is not only moral cowardice but dangerous. Consider the cases when otherwise good people participate in, or cover up heinous acts like sexual abuse out of a sense of duty to an organization (like a church or the Boy Scouts).

I prefer to understand duty as “the things you must do to have the relationships you want to have”. If you want to defend your country against all enemies foreign and domestic with guns, boats, and planes, you must join the military. If you want a loving, intimate relationship with another human, you must be honest, vulnerable, kind, forgiving, and communicate your thoughts and feelings. If you want to be involved in your community you must be willing to give your time, effort, and be open to criticism. There are no shortcuts and the outcomes are uncertain.

I feel like this understanding is a way of bridging the gap between our impulses toward utilitarianism and acting from a purely deontological perspective. We can pursue worthy goals while partially mitigating our errors in judgment and execution. A really compelling portrayal of Rama would depict his emotional turmoil as he navigates palace intrigue and the kidnapping of his wife. His inner struggles are implied by the text, but take moment to imagine the scene in his mother’s chambers: his lips drawn tight, his fist clenched as he is accused of being indifferent to the suffering his choices will bring. He wants to be king. He’s been groomed for the role from his youth. He’s just undergone the greatest reversal of fortune of his life, and now those closest to him imply that he is a coward or doesn’t care for their or the kingdom’s well being. Of course he feels the betrayal, he fears the potential peril, he knows his own ambition, but he also knows that he cannot honor his father’s word, he cannot be a trusted brother or son, he cannot be a just ruler if he gains power through defiance and subversion. He does what he must to have the relationships with his family and community that he desires. When Rama chooses to accept exile his fate is uncertain, but destiny is “unfathomable”, the truth is his fate is uncertain regardless of what he chooses. The thing he can control is how he treats his friends and neighbors, so he follows his Dharma. It’s not that Rama has totally relinquished desire or negated his individual existence; his personal desires are circumscribed within boundaries informed by the relationships he desires to have. I believe this is the essence of Dharma that fits not only my own preferences, but fits the historic understandings as presented in the texts I’ve discussed.

Further Support for the Relationship Theory of Dharma

Rama’s virtues are exemplified through his actions, but does the text say anything about prioritizing relationships? There aren’t explicit arguments about what type of person, and what types of relationships one should seek to support with one’s dharma. The story was originally composed within a cultural context in which those relationships and their obligations and boundaries were well defined, so I suspect this is a byproduct of the fact that the intended audience didn’t need these details laid out for them. The familial, caste/ varna, and gender roles aren’t explicitly defined for us, but are distinguishable. However, I think there are some universally applicable injunctions about human relationships that transcend culture sprinkled throughout the narrative.

One of the more explicit examples is when Rama’s father assesses his life before deciding to abdicate in favor of Rama: “I have in my lifetime given to the gods hundreds of offerings and sacrifices, and so paid my debt to them; I’ve studied and passed on what I learned that was not secret and so satisfied my teachers; I have fathered sons and so paid off my ancestors; I have given gifts to Brahmanas and other men, and made them happy, and they have no claim on me; and by enjoying a good life, I’ve pleased and paid off my debts to myself. All are paid. I will rule no longer”.

He clearly views his life as a series of relationships that he is duty-bound to maintain. The tragic flaw in his thinking is that he views them as transactional in nature. He’s paid his debts so he expects all to be well. Little did he know… The misery this perspective brings him is reminiscent of Job’s suffering.

There are other admonitions scattered throughout the narrative:

“Demons do not love men, therefore men must love each other”

“Never fear to love well. If you can’t bear it, who will?”

“Peace and Rama ruled as friends together. Men grew kind and fearless”

“People meet in this life and pass by each other like pieces of driftwood afloat on the wild and stormy sea, touching seldom, and once meeting, gone and parted again. Therefore a friend is also a treasure”

“If you find a friend, hold him if you may.”

“Giving to the poor, that is always right; or else, what you save is spent to buy a homesite for you in Hell.”

“Therefore shower gold, spend and be generous to those you love. For your sake spend your bright yellow gold, give gifts while you can and do good, choose your deeds well.”

“A friend is a protection against injury and a help for sorrow”

Finally, I’ll repeat one of the descriptions of Rama’s character development montage. I love this line because it recognizes our natural aversion to self-discipline, but advertises the benefits of doing so.

“To harsh words he returned no blame. He was warmhearted and generous and a real friend to all. Whatever he did, he ennobled it by how he did it. He tried living right and found it easier than he’d thought”.

So…What IS The Dharma Initiative?

I really enjoy this story and I can see why the television versions aired in India are among the most watched programs in human history. The premise and events are classical human dramas. The hero’s journey of a divine/semi-divine savior, the abducted wife, and the glory and renown of combat and triumph in a cosmic conflict of good and evil. Did I mention the underground monkey kingdom? The characters are relatable and inspiring. Study and reflection are rewarded. The messages are timeless. If I were to distill the text and time I’ve spent reflecting and writing down to a single sentence I would steal this one from Rama’s discussion with his brother Bharata, ”Since we have come together in this lifetime, let us keep the truth.”

I started this series with the question, “what is the dharma initiative?” Hopefully I’ve made a convincing case that the Ramayana presents an entertaining and compelling vision for how we can follow our dharma. One of my favorite aspects of the story is how the opposing ends of the spectrum of the impulse to protect and preserve are presented. Recall that “Raksha” the word from which Rakshasa derives means “I will protect”. Recall also that Rama is an avatar of Vishnu the god of preservation. Both good and evil can come from the same impulse. It is natural to seek to support and uphold a desired outcome by focusing on the end itself, but the divine pattern laid out in the Ramayana is to preserve through virtuous action and to let the chips fall where they may. We can cultivate and practice the virtues needed to foster fulfilling relationships regardless of any apparent expediency of compromising our character dictated by our ambition, desire, or fear. I think this is an inspiring and challenging vision for living