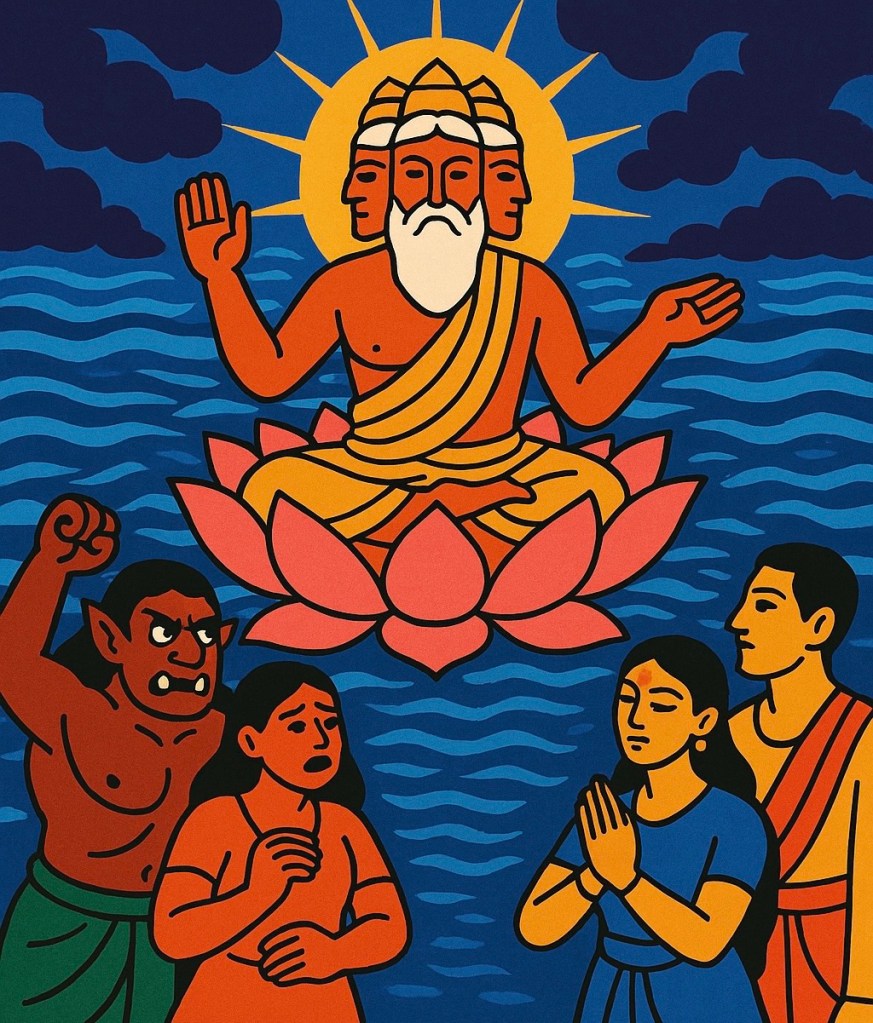

One way to examine an idea is to determine what it is not. The Sanskrit term for the opposite of Dharma is Adharma. I’d like to examine the most vivid presentation of Adharma in The Ramayana: Ravana. In the Vedas Dharma was linked with the processes of upholding divine order. Ravana overpowers the gods, disrupts the natural order of countless lives, and is eventually defeated by an avatar of Vishnu the god of preservation and order. The corruption he personifies is described vividly when Hanuman (the Spider-Man Monkey hero) sneaks into his palace at Lanka and finds him sleeping surrounded by concubines: “Ravana lay like a collection of wrongs, a mass of harm, and injury, and brutality, and darkness of heart”. Sounds like a great example of who we don’t want to be. Why is Ravana so evil? What’s his story? In my last journal I briefly discussed the origins of the Rakshasas, but I think a more detailed examination would be instructive.

Supervillain Origin Story

Let’s begin at the beginning, “At the beginning of Time as at every beginning, Brahma the Creator of the Worlds was reborn from a lotus… Brahma saw water everywhere and he grew anxious lest it be stolen. So out of the water he made four guardians; two mated couples male and female.

Those four people said “We are hungry and thirsty.”

Brahma told them, “Watch this water, don’t let a drop of it get lost.”

One couple answered him, “Rakshama, we will protect it.”

The other pair said, “Yakshama, we shall worship it.”

Those couples were the first Rakshasa and the first Yakshas.”

We don’t get much detail on the Yakshas, but their main activity transforms from worship to devouring. They make a single appearance in the narrative in the service of an incredibly wealthy “treasure king”. I think their arc is a great commentary on how a relationship with wealth can evolve from protection, to worship, to consumption.

We learn a bit more about the generations of Rakshasas and the circumstances into which Ravana is born. We learn the Rakshasas weren’t inherently evil. Most of them we know by name seem alright. The first child born to the original two Rakshasas is named Sukesa and he is described as “charming and polite”. Ravana’s brother Vibishana becomes one of Rama’s main allies in the siege of Lanka. He rules in Lanka for thousands of years after Ravana’s death and remains a steadfast ally. How exactly does one go from a heritage of protectors of creation to a supervillain leading a revolt against the gods at the head of an army of human devouring jungle monsters? The Ramayana uses an affordable housing crisis and wealth disparity.

Once the world is created the Rakshasas stuck around and are repeatedly shown in search of home. Sukesa had three sons Mali, Sumali, and Malyavan and “Those three young Rakshasa wanted a better place to live.” Viswakarman, the Hephaestus of the Hindu pantheon, fashions them a golden city on the island of Lanka. We learn, “The race of Rakshasas flourished under Sukesa’s three sons…. But as they increased in number there was not room for every Rakshasa to live in Lanka. Some left the others and prowled, roaming through the forests across the seas to the north, and there began to eat the raw flesh of men”. The evil Rakshasas and a major crime wave were born out of an affordable housing crisis. I say affordable because I’ve got to imagine constructing new gold buildings to expand Lanka wasn’t cheap. This crime wave resulted in a visit from Narayana (a prior incarnation / avatar of Vishnu) who defeated and scattered the Rakshasas away from Lanka. This housing crisis may or may not be directly related to income inequality; we don’t know much about Rakshasa economics, but some criteria must be used to determine who lives in gold houses and who is homeless. One thing we definitely know is that these social factors lead to a crime wave, war, and the entire group ends up deprived of its homeland and is displaced and scattered. A group of people displaced from their traditional homeland become a disruptive force in the world. Where have we heard that before?

It is into this version of Rakshasa society that Ravana, his two brothers, and sister are born. One of his brothers, Kumbakarna, is bigger than a house and spends much of his time sleeping. His sister Surpanakha fatefully pursues Rama and brings Sita’s beauty to Ravana’s attention. Vibishana is described as “the good demon” and he will ultimately rule over the Rakshasas following Ravana’s defeat. Ravana has 10 heads and 20 arms so he cuts an impressive figure. One day Ravana and Vibishana saw the Treasure Lord fly across the sky on his flying chariot and we are told, “Ravana became sad that he had no such brilliance himself.”

A note here on the “Treasure Lord”. He is the “mind born son” of Brahma (sounds like an Athena/Zeus situation), he has a magical flying chariot, and he takes control of Lanka when the Rakshasas are displaced. Is there a “dad likes his new kid better” vibe here? Is there jealousy because of his wealth? The dude is known as the “Treasure Lord”. He inherits in the traditional Rakshasa homeland of Lanka. Seeing the rich cousin fly around in his magical car, going to and from your parent’s former home has got to induce some level of jealousy. We aren’t privy to the exact details of Ravana’s feelings, motivations, and goals, but after becoming “sad because he had no such brilliance for himself” he and his brothers enter on a project of self-improvement.

The brothers “sat contemplating the absolute immensity of life. In contemplation they entered Eternity”. Transcendental meditation seems like an unlikely supervillain origin story, but that’s what we’re given. Ravana was definitely playing the long game. “At the end of every thousand years, Ravana cut off one of his heads and threw it into a fire as a sacrifice, until nine of his heads were gone and only one day remained before he would cut off the last one. That day was passing. Ten thousand years and Ravana’s life were about to end together. Ravana held the knife to his throat, when Brahma appeared and said ‘Stop! Ask me a boon at once!’“.

Ravana replies “May I be unslayable and never defeated by the gods or any one from any heaven, by Hell’s devils or Asuras or demon spirits, by underworld serpents or Yakshas or Rakshasas”.

Brahma grants his request.

The Rise to Power and Fall of a Kingdom

Armed with this power Ravana pays a visit to Lanka. He demands that Vaishravana, the “Treasure Lord”, leave. Vaishravana relocates to a mountain north of the Himalayas. Not a single shot is fired and Ravana has regained the homeland for the Rakshasas. The full version may have more details, but Buck’s retelling doesn’t mention any specific threats or harsh language required for the task. The threat was certainly implied, but the point is that Ravana is capable of tending to his needs and the needs of his people without plunging the world into violence and chaos.

All the Rakshasas are happy in their new home, but Ravana doesn’t stop there. There’s a critique offered later in the story that “Ravana had the patience and strength to protect all Creation from harm, but he did just the opposite and took the worlds for his possessions”. His ambition extends beyond regaining a homeland, wealth, and status. There’s something more going on here. Like Alexander of Macedon, Ravana takes his triumphant army and begins conquering and pillaging all over the subcontinent. Many of the refugees flee to Vaishravana’s new kingdom and he is forced to address the situation. Here we see yet another case when appeasement fails to satiate the aggression of one possessed of a desire for power and wealth. A messenger is dispatched to warn Ravana that “this aggression will not stand” and Ravana kills him and sends his body “to the kitchen to be roasted and served, and his bones made into broth”. Those familiar with the story of Tantalus and The House of Atreus will recognize this M.O. Battle between Ravana with his Rakshasas and Vaishravana allied with the Yakshas follows.

I love the way this battle is described. “Manibhadra (king of the Yakshas) flew over the walls like a hawk, followed by whirling flame-crested Yakshas spinning in the air, filled with the energy they had stolen from careless treasure-lovers in the big cities of men, and crying their war cries ‘Yes. No. I don’t want. Let me have. More!’” The idea that these demons, whose name can be translated as “devourers”, harness desire for wealth as fearsome weapons is a splendid image. One of Ravana’s lieutenants comes up against the Yaksha king who “put fear of loss and hope of gain into [his] heart in exactly equal parts and so paralysed him”. Despite this weaponization of greed Ravana and his forces win.

For the most part, the subsequent conquests of the gods aren’t nearly as entertaining as the fall of Vaishravana. The exception is Ravana’s back and forth with Time and Death which is thought provoking, but would require a digression longer than I’m willing to go for right now.

Ravana’s conquests precede Rama’s birth so we next encounter Ravana a hundred pages later after he has been enthroned in a golden palace at Lanka for an untold number of years. He is married to the daughter of Maya (god of illusion) and has a son, but spends his nights surrounded by hundreds of concubines. However, when he hears of the beauty of Sita from his sister he determines he must have her. This decision eventually leads to the siege of Lanka and Ravana is confronted with the stark reality of his desires resulting in the suffering and deaths of thousands.

The thing is: he’s done this before. You can’t conquer cities without killing and displacing who knows how many innocents, but he’s always been on the winning side, and the victims weren’t his closest friends and family. All of that changes in the Siege of Lanka. In addition to the frontline soldiers lost in the war, a second brother, as well as his long-standing advisor are both slain. These losses, while painful, aren’t enough to persuade him to relinquish Sita. Eventually even his own son, a powerful warrior whose mystical abilities allow him to devastate the enemy from under a cloak of invisibility, is killed. Nevertheless he persists in his refusal to relinquish his captive. Eventually Ravana is killed in one-on-one combat with Rama. He loses family, friends, wealth, power, and his own life in a precipitous calamity of his own making. There must be a lesson in Ravana’s rise and fall from which we can learn.

Your Wrongs Devour Us

Ravana’s downfall is a mixture of tainted judgments and impulses corrupted by power, based on a skewed vision of the world, enabled and reinforced by sycophancy. A pretty standard model of disaster. See: Louis XVI, Napoleon, Nicholas II, Adolf Hitler, Richard Nixon, Harvey Weinstein, R. Kelly, Sean “Poofy” Combs, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump.

While many of us find this combination repulsive, history and contemporary society suggest there are always those who will admire the Emperor’s new clothes. After Hanuman escapes to tell Rama where Sita is being held captive, Ravana gathers his counselors and asks, “What must I do? The superior person will gladly take good advice before acting.”

They respond, “Yes, we agree! Majesty, you rightly rule the Universe. Everything’s been just fine so far.”

“You are Ravana, King of the Night-Wanderers. You are Lord of Lanka on the Waves, the Protector of Heaven and the Guardian of Truth, the Defender of Love and Enemy of Evil. In anger you are a dark stormcloud threatening all that is wrong and moving if you will against the wind. You have jailed lies and imprison all deceit- Majesty, rule right forever!” Most of us aren’t surrounded by folks like these, but we’re all capable of this type of self-deception.

The thing is there were those willing to speak truth to power in Ravana’s circle. In fact those whose judgments he should have, at least in theory, valued the most; his brothers, long-standing advisors, and his son gave him honest and frank assessments of his behavior and counseled him with wisdom and love.

Ravana’s brother Vibishana counters the flattery offered by others, “Are you incapable of reason? Do you want to live on congratulations and embraces and elegant flattery?… Open your eyes and mend your ways, wake up and do right!… You are a slave and wrath your Master.” This good advice gets him banished.

Following setbacks on the field of battle Ravana awakens his brother Kumbhakarna who is a giant that sleeps for years at a time, and after being brought up to speed says, “You are speaking of the waking world of impermanence, of suffering and unreality…. Your entire education was a waste… After you’ve done this thoughtless deed full of flaws and holes, then you call on me. You’ve begun at the end and ignored the beginning… There’s no greater wrong than stealing another’s wife. Lord of Night, what else but a harvest of misfortune could follow? Everyone here who has been awake and kept silent about your careless love is your fawning enemy.”

After Kumbhakarna is killed Ravana begs his son Indrajit to use his power of invisibility to defeat Rama’s army. Indrajit points out the errors of Ravana’s behavior and mounting evidence that the cause is not only unjust, but doomed to failure, “Even if Time and Death themselves overlook you when your life is full you can find no safety from Rama if you keep his wife. There is always a choice, Father – the Way of Life, or the path of Death… However great you may be, do not live hostile to every other soul.”

While I think the proverbs across cultures about the relationship between power and corruption hold water, the Ramayana suggests Ravana harbors a deeper flaw that was only magnified by power. Many religions and philosophies accept the belief that desire is linked to suffering. The Greek (pathos) and Latin (passio) words from which we derive our term “passion” can also be translated as suffering. The Ramayana repeats this insight multiple times in the mouths of its characters.

Ravana’s foray into transcendental meditation was driven by his desire to have glory like the Treasure Lord. When his city is under siege and the losses mount and his world is crumbling around him he recognizes, “I have lost myself in longing”.

Prior to abducting Sita Ravana’s uncle counseled him against it, “Rare and unpleasant is the truth to an idiot King, but this greed will draw you swiftly to your doom.”

Indrajit reaches further into the past, connecting many of Ravana’s decisions to their present turmoil, “Think for a moment, remember the past… You drove out kindness, and denied freedom to the Universe, and made Creation suffer. The worlds are large, but your selfishness overmatched them. Now your wrongs devour us.”

Two Sides of The Same Coin

Let’s consider the validity of this claim that suffering and desire are intimately linked. Desire is a manifestation of intent, so by definition we have “chosen a side” and are pursuing a specific outcome. Obviously, when one fails to achieve that outcome we will have an adverse emotional experience. Do disappointment, consternation, and frustration count as suffering? That word may seem a bit strong, but I think it’s appropriate. There is definitely a difference in magnitude between disappointment that I didn’t get the part I wanted in the school musical, and I didn’t get the job I need to pay my bills and support my family, but my experience tells me they share an emotional quality. Also, experiencing something you definitely desired NOT to happen produces a very similar form of emotional suffering. Anyone who has children can tell you the emotional distress induced by the mashed potatoes touching the green beans is very real.

One can claim that these sort of emotional experiences may be “overblown” and irrational: see toddler, pre-teen, teenager, celebrity, athlete, and politician meltdowns. The fact that these types of experiences are ubiquitous and relatable tells us humans are not “rational beings”. We are beings capable of reason while we navigate a profoundly emotional existence, and suffering linked to desire is a pervasive part of that experience. To wit, survival is a manifestation of the desire to continue existing, anything that threatens or that we perceive to have an adverse impact on our experience of existence can produce suffering, ergo to exist is to suffer.

We’ve considered Rolling Stone type scenarios of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”, but what happens if you try, and sometimes you get what you need? Does obtaining your desire prevent suffering? Ravana’s rise and fall are constructed to teach this lesson. But his desires were centered on wealth, power, and abusive authority. Surely, wholesome desires for comfort and intimacy aren’t sources of suffering.

As the days go by you may find yourself in a beautiful house with a beautiful wife, or you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile.

Do those with loving families, good jobs, beautiful homes, and large automobiles ever suffer because of their success?

Do they worry about losing them? If they subsequently find themselves living in a shotgun shack do they exclaim, “This is not my beautiful house!”? Do they worry about what may happen to their loved ones? “This is not my beautiful wife!”. Do they get upset when someone steals their car? “Where is that large automobile?”

Do you ever suffer from a lack of fulfillment despite all you have? You may ask yourself, “well, how did I get here?”, “how do I work this?” And you may ask yourself, “my god, what have I done?”.

In my experience the anxiety produced by the inevitabilities of time and loss is a credible form of emotional anguish or suffering. Especially when the anxiety involves the wholesome and fulfilling aspects of our lives. Therefore success and failure really are two sides of the same coin of desire. Same as it ever was.

At first glance this may be a discouraging insight. However, there are those who claim recognizing this connection between desire and suffering is not to be feared or begrudgingly countenanced, but is actually liberating. Many will recognize the formulation “existence is suffering” as one rendering of the first of the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. The Buddha formulated his teachings as a treatment leading to the end of suffering. Buddhism isn’t the focus of this discussion; I mention this to highlight its shared insights with Hinduism. If existence is suffering, and if one seeks the cessation of suffering, then one desires an end to existence. This may sound undesirable within the context of western theology with its prime directive of seeking eternal life, but an exit from the realm of Samsara is the explicit goal of Moksha (Hinduism) or Nirvana (Buddhism). In light of the doctrines of Reincarnation and Karma, the idea of simple self-annihilation through suicide fails to solve the problem. Take that Albert Camus. It stands to reason that within these traditions there must be specific forms of desire and behavior which proliferate suffering and generate bad karma which trap one in the world of samsara and prevent liberation and release. If sin and death are the primary problems of the Abrahamic tradition, then it seems reasonable to argue that suffering and existence are the primary problems of the Vedic tradition. The exploration of these problems has invigorated discussion among practitioners of these religions for thousands of years and thankfully a complete exploration of these thoughts and practices is beyond my purposes. That said, I believe that a better understanding of our experience and the relationship between our desires and suffering are worthy goals.

He Took The World For His Possessions

If we want to move from the general to the specific and Ravana represents the ultimate in Adharma, then it would be fitting for some aspect of his character to suggest the types of desires and behaviors that should set off alarm bells when we encounter them in ourselves and others.

There is the obvious drive for wealth and power. I think the fact that he is inspired by and defeats the “Treasure Lord” Vaisravana, yet remains unsatisfied teaches the nearly universal understanding about the disconnect between wealth, power, and fulfillment. Don’t worry. I haven’t tapped out thousands of words just to get to “the love of money is the root of all evil”. I think the Ramayana makes the case that even these potent desires are specific examples of a more general phenomenon. Ravana’s interactions with Sita as his captive are evidence that the twin desires for possession and control underlie the actions that produce so much suffering.

Prior to kidnapping Sita, Ravana tries to talk her into going willingly and this interaction made me write “Boom! Roasted!” in the margin of my copy.

“Beautiful, I am the Rakshasa King Ravana. I rule the universe. Come to me, Sita. I will take you to Lanka with her engines and weapons, and I will put you over all my other Queens.”

Sita Laughed, “Garuda (a divine eagle) mating with a goose? A firefly courting the sun?”

Boom!

Ravana responds, “Don’t play around with me!”

To which Sita rejoins, “I won’t, don’t worry”.

Roasted!

After a bit more back and forth Ravana declares, “I will have you!”

Later, after Hanuman jumps across the sea in search of Sita, he watches an interaction between Sita and her captor.

Ravana talks a lot about his wealth and power and tries to tempt her with the same, “Rule over my other wives and my city as you rule my heart. Why hold yourself back? If you command it, I will do good to all the world. Favor me, dear Sita.”

Sita understands his position very differently, “You see everything reverse, You are a magician selling sunlight as if you owned it.”

Ravana rages, “The nicer I am, the worse you treat me! RRRrraarrR!”.

Notice how he offers power and control, and is frustrated because he cannot force or even sway his captive to love what he assumes she wants. His existence is defined by possession and control. His first wife Mandodari, takes him by the arm and leads him away saying, “Whatever you will, my dear Lord, whatever you say”. The servants assigned to guard Sita are shocked by her resistance because “Their eyes could see no more than a prisoner unarmed, alone and powerless” which sounds like objectification induced by an equation of possession and control with power to me.

I really like how Ravana is described when Hanuman, after being captured during his reconnaissance mission to find Sita, is brought before the king. “There on his red and gold throne, in a better hall than any room in heaven, the Demon King sat like threats of darkness. Ravana had earned all his wealth and power by his own strength (self-made man). He was fortunate and splendid and rich. Ravana had the patience and strength to protect all Creation from harm, but he did just the opposite and took the worlds for his possessions.”

I think the impulses to possess and control as the deepest roots of harmful desires and unnecessary emotional suffering rings true in general, and specifically in the case of Ravana. He is a Rakshasa “I will protect”. Possession, and control often go hand in hand with the concepts of preservation and protection. He is surrounded by astounding wealth, yet he seems to have no vision for what to do with it. He has literally subjugated the gods, but institutes no directives or policy as to their roles or how the cosmos works. How many seem to have no ambition beyond accumulating more wealth, prestige, and power? There are plenty of lyrics to love in the classic ”Everybody Wants to Rule The World” by Tears For Fears, but my favorite couplet is “I can’t stand this indecision married with a lack of vision”.

He rejects those who genuinely love him and have his best interests at heart and sacrifices their lives in the interest of maintaining control over a woman he desires. There is added situational irony in this behavior. Ravana has a curse laid upon him that he cannot have sexual intercourse with a woman who does not do so willingly. He holds Sita captive for a year and never fulfills his desire for her as she steadfastly refuses his advances and threats.

Related to the mistaken correlation between possession, control, and fulfillment; in his book Mere Christianity C.S. Lewis writes “Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man”.

In his book Alone With Others, Steven Batchelor develops the concept of the dual/ competing facets of human experience which he terms “the dimension of having” and “the dimension of being”. I find his arguments well articulated and compelling. I won’t try to summarize them here because I don’t think I’m in a position to do them justice, but I like the way he describes some of the consequences of having our vision and minds occupied by “having”

“Progress has come to mean the ever increasing ability to accumulate lifeless objects within the greatest possible number of fields. Aptly we have dubbed ourselves “the consumer society.” Even our own bodies and minds are regarded as ‘things’ we ‘have.’ Life is said to be the most valuable thing we possess. Consequently, body, mind, and life are all looked upon as objects that ‘I’ can somehow keep or lose. Here, as in all acts of having, a gulf is created between the possessor and the possessed. Having always presupposes a sharply defined dualism between subject and object. The subject thus seeks his or her well-being, as well as his or her sense of meaning and purpose, in the preservation and acquisition of objects from which he or she is necessarily isolated… however hard we try, we will never succeed in filling an inner emptiness from the outside; it can only be filled from within. A lack of being remains unaffected by a plenitude of having.”

Ravana’s M.O. is to possess and it drives attitudes and behaviors that result in enormous quantities of suffering. Countless lives are lost in conflicts he instigates. Families and societies are displaced. His desire to possess and control disrupts all of creation and results in the deaths of those closest to him who love him. Driven by his desire for control he brings about his own destruction. This is repeatedly presented as the ultimate departure from Dharma.

The Potential and Peril of Shared Fiction

If we take a hard look at the universe and our experience of it we can appreciate that concepts of control, possession, and ownership are not representative of absolute reality, but are shared fictions. They’re stories that we tell about our relationship to the world that are nearly universally accepted, but they aren’t actually true. Recognizing a thing as a fiction doesn’t mean it’s a fraud, or even counterproductive; shared fictions can be really useful. A less pejorative sounding term one could use in place of “fiction” is “convention”, or “intersubjective”, but I’m gonna stick with fiction in this discussion because that’s how I roll.

Language is a shared fiction. The sounds and symbols have no intrinsic meaning, but to those who share in the fiction of a language the power of the human mind can be amplified as ideas are exchanged, plans are hatched, and coordinated effort produces magnificent creations. The ability to adopt shared fictions is an amazing feature, not a bug, of being human.

Another powerful, dare I say dominant, shared fiction is money. Money, especially banknotes and digital accounting, but even gold and “precious stones”, aren’t inherently valuable. Precious commodities were sitting around on the planet for billions of years, humanity decided they were valuable. There may well be asteroids floating around in space composed of quintillions of dollars worth of “precious” ore. The elements simply are. Physics endows them with specific properties, but it is our desires that make them useful. It’s only our willingness to work to obtain them and a consequence of affixing a monetary value on them that makes them “valuable”. Exchange can happen without money, but fungible tokens: be they fancy shells, gold nuggets, translucent stones, pieces of paper, or 0s and 1s on a silicon chip can all grease the wheels of trade considerably. Nobody can credibly argue otherwise.

I would suggest ownership, possession, and control are conceptually adjacent. We tell ourselves they exist, certain aspects of life as we know it are predicated upon shared acceptance that they exist, and we badly want them to be real, but are they?

I think the idea that physical, or social dominance: ownership reflects a reality of control is faulty. An obvious example is land “ownership”. The idea that a human with a lifespan of roughly 100 years can ”own” or “control” a piece of a planet that is 5 Billion years old that will be here long after that human’s death is ludicrous. Exploitation, in the non-pejorative sense, is not the same as control.

Think through the implications of our current concepts of land ownership, mineral and water ”rights”, and political borders. Because of our shared belief in land ownership an individual or group can make decisions resulting in externalities with short and long-term impacts on many lives and the health of the environment. These decisions can create political stability and enormous wealth which are perceived as short-term “goods”, but can also have devastating long-term results which are far more pervasive. The obvious example here is fossil fuel extraction, but mineral extraction, water reclamation/hydropower generation, agricultural production (sugar cane, indigo, and cotton are the obvious historical offenders, but the water politics of the Western US and alfalfa exports to China are very real concerns in my state of residence) and even a concept as fundamental as political borders are all double-edged swords that have induced generations of human suffering. Regardless of whether or not the dire outcomes of climate change models occur, I don’t think anyone could convince me that our concepts of land ownership and resource exploitation are unalloyed goods.

Until this sentence I’ve avoided invoking the extreme extension of the concept of ownership to human beings. You may disagree with me about the ability of an intelligent, conscious human being to own inanimate matter, but I suspect you would bristle at the claim of a fellow human asserting ownership rights over you. I know I would. Yet, for the majority of human history this fiction was widely shared.

Next consider the relationship between our lives, work, compensation, and our “possessions”. If you must surrender something approaching half of your waking life working to procure the (fictional) means by which you purchase a thing, do you actually own or control it, or is it the other way around? You’re the one who gave up a piece of your life to get it.

This confusing relationship goes all the way back to the beginnings of civilization. We domesticate and cultivate species for our purposes, but there are tradeoffs. As certain desirable traits are magnified the cultivated species often becomes dependent upon increasing levels of human labor and ingenuity for its survival. In turn humans also become increasingly dependent upon the surplus calories provided by the domesticated product to support our lifestyles and population. Did we domesticate stock animals and crops, or did they domesticate us? Did civilization lead to agriculture or the other way around? Did we domesticate wolves to assist and protect us, or did they train us to give them food scraps and belly rubs? 😉

The lesson to be learned from the domestication question is that in successful enterprises we don’t see unadulterated possession and control; we observe interdependence and sometimes cooperation. The relationship is always a two way street. Shared fictions can be very useful, but like any proxy for reality, when taken too far, or when they are mistaken for the genuine article their limits and flaws are exposed.

Bottom line: ownership is a fiction and possession and control are illusory. Hinduism has a word for this: Maya. Recall Ravana’s first wife Mandodari is the daughter of the god of illusion. Recall also that Maya is taught to be a major contributor to the confusion and suffering of Samsara. Ravana literally and figuratively embraces Maya and I don’t think it is coincidence that he significantly exacerbates the suffering of many in this realm of Samsara.

Returning to the harm that rises from Ravana’s desire to possess and control: I don’t think it is mere coincidence that basically every culture has adopted myths that teach that greed and control are harmful and dangerous. However we live in a culture that has chosen to harness the power of greed, possession, and control, and even pose them as virtues. Talk to just about any white male college sophomore from the late 1990s about Ayn Rand. The resulting prosperity as measured by wealth, possessions, and even certain metrics of quality and quantity of life is undeniable. However, we shouldn’t be surprised that we are also experiencing tradeoffs from these decisions.

I’m not an expert on the validity of the available data or research, but I’m 100% certain that where there is income, there is income disparity. Where there is wealth there is also poverty. Inequality of resources necessarily results in disparities of access to needs and wants of life. Not being able to afford the latest gadget may not be a big deal. Not being able to access quality housing, nutritious food, clean water, clean air and care for illness constitute far more than just emotional suffering. See my discussion of the Rakshasa affordable housing crisis that gave rise to Ravana.

Warnings about the connection between desire, possession, externalities, and suffering is not unique to eastern traditions. An injunction against seeking possession and control made its way into the Judeo-Christian top 10 as well.

“You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, male or female slave, ox, donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor.” Exodus 20:17

Additionally, If we direct our focus inward I suspect we can all recognize the distress we’ve experienced when the idea that we control our own lives has been challenged. What we call good health is certainly influenced by our choices and behaviors, but is subject to a significant dose of luck as well. I may have a malignancy developing in me right now and may not learn about it until it’s too late to do anything about it. If we don’t exercise genuine control over our own bodies, how much order can we expect to impose on the physical world, current events, and the future? “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns…. which of you by worrying can add a single hour to your span of life?” (Matthew 6:26-27) It seems Ravana was not alone in his compulsion to possess and control. He didn’t suffer alone either.

If desires for possession and control are the primary drivers of Adharma, what is/are the root(s) of Dharma? This is basically where we started, and I think we’re well positioned to dig into what the Ramayana presents as the “answer”.