One thing the reader should know about The Ramayana is that like my own writing, it is full of detours, digressions, and flashbacks. Based on my admittedly limited experience with The Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Bhagavad Gita this complex structure appears to be characteristic of the genre. Sometimes these techniques can be disorienting. One minute you’re progressing through the main plot, and the next you’re transported to the distant past. One level of disruption in a timeline is pretty standard in modern storytelling, but sometimes there’s a Russian Doll type thing going on and the stories can nest three or four levels deep and it can be a little taxing to keep track of where you are, especially if you’re reading at bedtime and occasionally fall asleep during the telescopic narration. I suspect this convention occurs for at least two reasons. A little bit of jumping back and forth actually makes for a more engaging story, and the flexibility allows for embellishment and accretion of more detail as a story morphs from folktale to culture defining epic. A storyteller can easily fill plot holes, or add post hoc justifications to make the narrative conform to shifting norms and beliefs. It also allows the teller to develop characters and perform world building.

For example in The Ramayana we learn the “original” composer of the Ramayana, Valmiki, long ago was disaffected by the cruelty of the world and went to the forest to become a hermit, he spent thousands of years buried in termite mound, and ultimately was awakened and chosen by the gods to invent poetry by composing this exact story.

Anyone else getting vibes adjacent to Tenacious D’s “Tribute”? To top it off, he actually enters the story when he acts as a surrogate father for Rama’s sons after they and their mother were banished from Rama’s court. This isn’t the only story to include a narrative about its own creation. It is a fairly common feature of scripture and is not so different from the opening line of The Odyssey when the composer invokes the aid of the muses to tell the story of Odysseus polytropos, just way longer and more involved. This introduction is followed by a flashback to a conversation between king Dasaratha, Rama’s father, and his spiritual advisor in which the king learns the history of the present turmoil among the gods which foreshadows his son’s fate and role in the cosmic drama. If those two bits of information feel like a whirlwind of activity then I’ve communicated my impressions effectively. This may be a byproduct of the retellings I’ve chosen, but these types of things occur often enough that I’m convinced it’s a bonafide convention of the genre. I lead with this information because I’m going to deprive the reader of a lot of the details and enjoyment of those telescoping effects, if you doubt my claims, or want to experience this for yourself I’ll summon the words of the wise Lavar Burton, “you don’t have to take MY word for it…”

How It Started vs How It’s Going

The universe is out of order when the Ramayana opens. Humanity is only dimly aware of the extent and underlying causes for the disorder, but we soon learn the problems have their roots way back in the creation of this version of the cosmos and the gods are powerless to repair things. The story goes that when Brahma awoke from his slumber and decided to recreate the universe he first separated the waters (sound familiar?), and fearing that something would disrupt the creation process, crafted beings to watch over and protect his project in beginning stage.

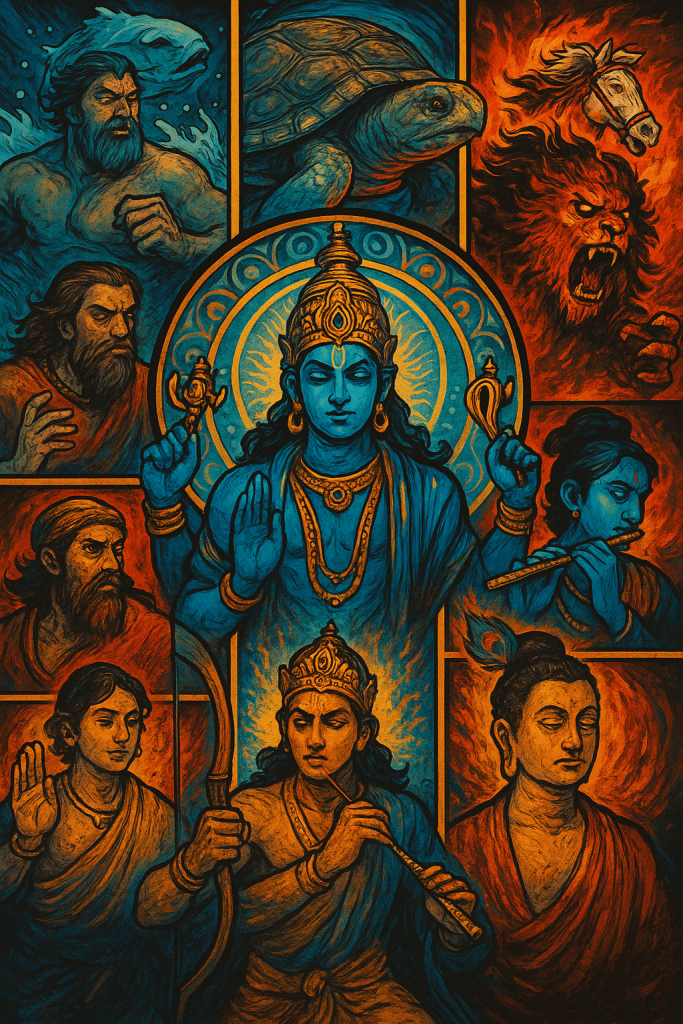

These beings apparently became obsessed with doing their assigned jobs well, and like rogue robots from sci-fi thrillers this focus put them at odds with a resulting dynamic creation. It’s like they couldn’t handle the changes that followed their own creation and went a little overboard. They developed into Yakshas and Rakshasas. Both are members of the Asura class of celestial beings. Asura is often translated as “demon” which is in obvious opposition to the Devas generally “the gods”. Brief digression: One support of the postulated proto-indo-European language hypothesis and the shared roots the Aryan people is that early Iranian (notice the similarity to Aryan?) religion had Ahuras and Devas, but their roles were reversed. Those with a passing knowledge of Zoroastrianism which grew out of early Iranian religion will note that the name of the supreme being is Ahura-Mazda. How and why the nature and roles of these classes of divine beings was reversed among the Indo-Aryan migrants who populated the subcontinent is not known.

Anyway, the Yakshas whose names mean “to gobble” grow into a flavor of being who consume as their mode of protection. Among their objects of consumption are humans, and they enjoy a great cameo in the story with an interesting commentary on wealth accumulation. The word Rakshasa derives from “to guard” or “preserve” and it is this line of being that gives rise to Ravana the antagonist of the Ramayana. He has a great supervillain origin story and we’ll discuss his motivations, behaviors and character at length elsewhere, but for now just know that his heritage is one of guarding against loss or undesirable change.

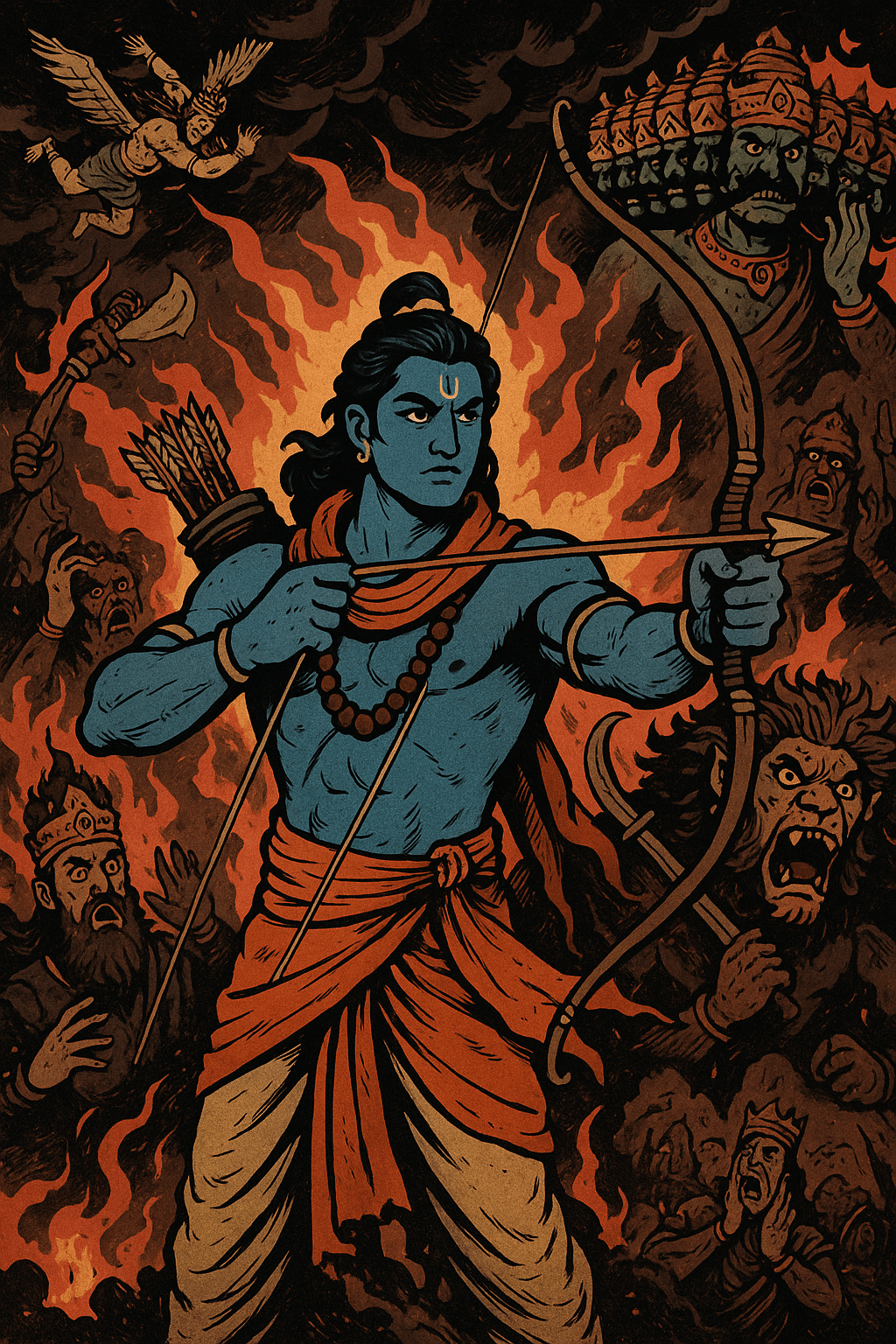

There’s a brief history of the Rakshasas that brings us to Ravana’s youth. Following a moment of jealousy over a flying car he dedicates ten thousand years to transcendental meditation. This commitment combined with a pretty bold stunt of chopping one of his ten heads off every thousand years results in him being granted the superpower of being impervious to death from the gods.

He then rampages across heaven and Earth eventually defeating and subjugating many of the principal deities of Hinduism. The gods are helpless to reverse these events.

Of course his immunity against the gods does not render him invincible. He can be defeated by an animal or a human. But why would anyone worry about weak, puny humans? Of course we know one underestimates the capacity of mortals at one’s peril, just ask Sauron. Vishnu, god of preservation, offers to take on human form and restore the natural order of things. To recap: a malign force is causing chaos and suffering down of Earth, so a god is born as a human to restore peace and divine order. Where have I heard that before?

Emmanuel

Rama and his three brothers are all born essentially simultaneously under miraculous circumstances to the prosperous, but previously childless, king of Kosala and his 3 wives. Technically they’re mostly half-brothers (there is a set of twins) and the specter of nasty dynastic politics looms in the background. However the text makes it clear that Rama is the best. At everything. He’s brave, kind, patient, helpful, humble, physically powerful, and seems to possess every desirable virtue.

“He didn’t give good advice and tell others what he thought best and show them their mistakes…. He knew his own faults better than the failings of others… He didn’t believe that what he preferred for himself was always best for everyone else…. He tried living right and found it easier than he thought. Rama would not work very long without a holiday; he wouldn’t walk far without stopping to greet a friend, nor speak long without smiling… He would often find a new gift for his friends. He did not fear to pass a whole day without work. Whatever he did, he ennobled it by how he did it”.

I love this list of virtues. If you find one or more of them surprising, I would suggest this is a great opportunity to consider our inherited cultural biases. My personal favorite: “He tried living right and found it easier than he thought”

While on an adventure as a youth he stops by the city of Mithilia. He is presented with a challenge. Whoever can string Shiva’s bow wins the hand of the king’s daughter in marriage. Where have we heard that before? He does so, and the bow that no one else could even string snaps into pieces when Rama draws it back. Nonetheless he earned to right to ask for the girl’s consent to marry. The response is immediate, “she has seen him from her high window and touched him with her eyes and fallen in love with him already.”

Basically men want to be him and women want to be with him.

After years of cultivating virtue in faithful service to his father and the kingdom ensconced in a loving marriage while performing brave deeds making the world safe for those seeking to worship the gods in peace from those darn Rashasas that seem to be running amok in the forest, Rama learns that his father will abdicate and he will be crowned king.

The assembly of nobles and just about everyone else in the kingdom is super stoked by this announcement. The city is abuzz with excitement and activity as preparations are rapidly made for the coronation. Even Rama’s step-mothers and step-brothers are enthusiastic about his coming reign.

What about the nasty dynastic politics I mentioned earlier? A maid-servant of his step-mother Kaikeyi insists this will be the beginning of the end for her and her son. Kaikeyi descends into panic and eventually determines to call in two favors King Dasaratha promised her years ago when she saved his life. She demands her own son Bharata be crowned king, and that Rama be exiled in the forest for 14 years. Dasaratha is heartbroken, but is also a man of his word and he grants these requests. However he, and many other family members including Bharata, his royal advisors, and the general citizenry all encourage Rama to use his strength, popularity, and common sense to oppose these decisions and seize the throne anyway. Rama refuses. This sequence is an obvious turning point in the narrative and merits close examination as it has a lot of implicit and explicit discussion of dharma. Trust me we’ll return to its details.

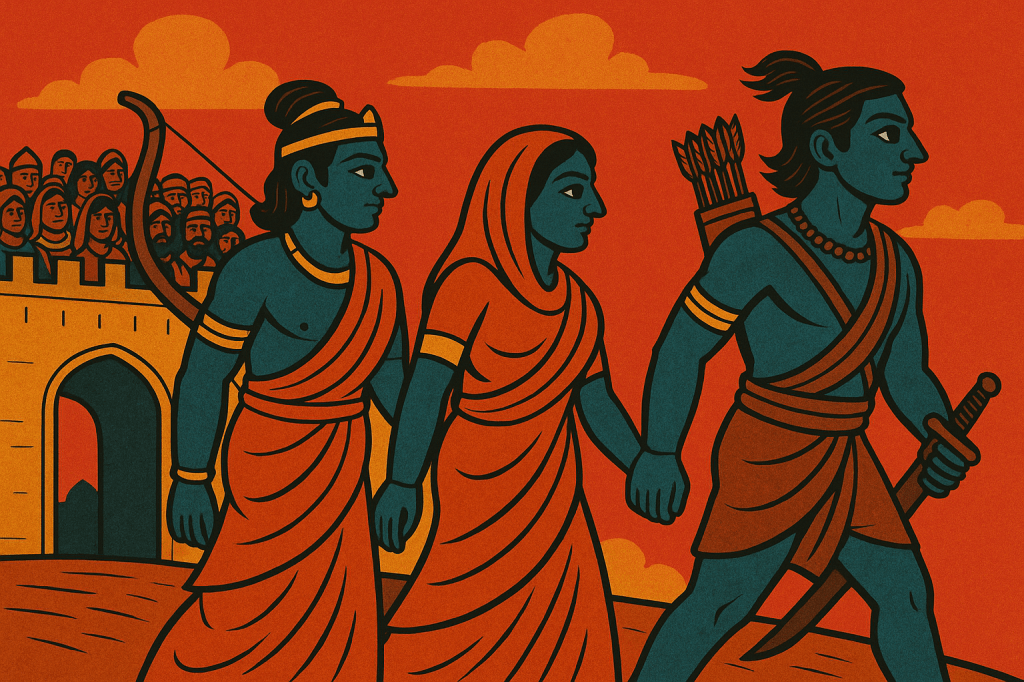

Pilgrims in the Forest

After a lot of drama and intense debates Rama, his brother Laksmana, and his wife Sita all leave for 14 years of exile in the jungle. The next 13 years pass pleasantly and we meet a few colorful characters as the happy triumvirate move around. One day a female Rakshasa decides Rama is a handsome fella she wants to “know” a bit better. A femme fatale. When Rama rejects her aggressive propositioning and defends himself with force which disfigures her, Shurpanakha retreats back to her brother’s palace. Her brother just so happens to be Ravana. A conflict looms.

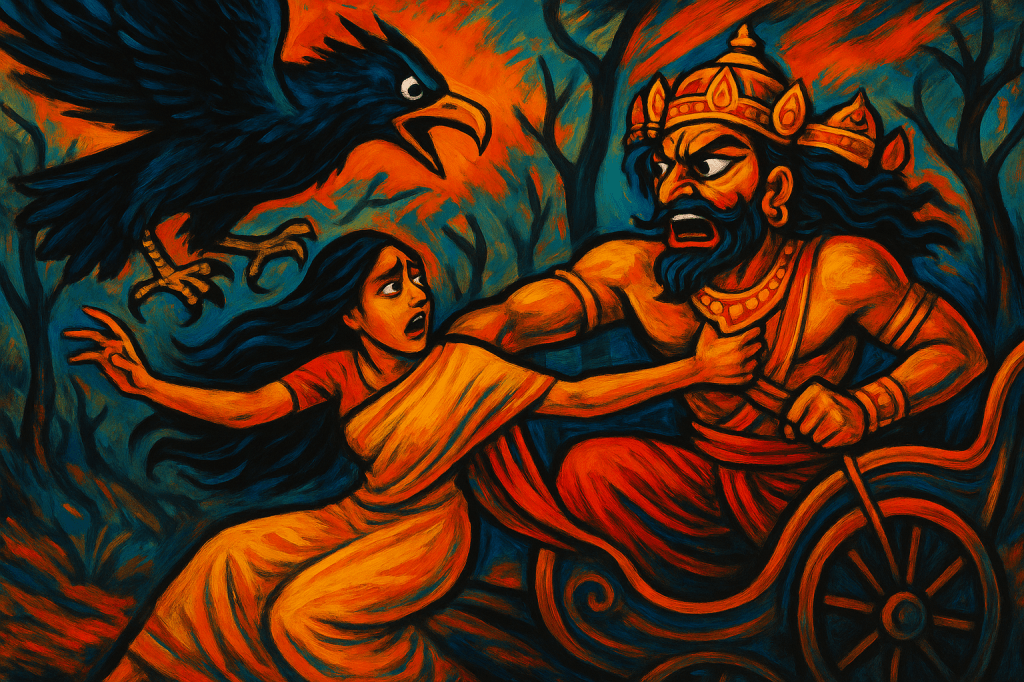

Shurpanakha demands justice against this human for insulting her honor and defiling her beauty. A contingent of warriors is dispatched and Rama and his brother handily defeat them. As Shurpanakha is stewing in her fury she lets slip how devastatingly beautiful Rama’s wife Sita is. Ravana’s interest in this whole affair suddenly increases. Next thing we know he and his uncle, who has already been defeated in combat by Rama years ago, are off to see if Shurpanakha’s description is accurate. It is.

Ravana hatches a plan to separate Rama and his brother from Sita. It works. Ravana then abducts Sita and there’s a great high speed chase involving a heroic vulture, nonetheless Ravana returns with his hostage to his golden palace across a channel from the mainland in (Sri) Lanka.

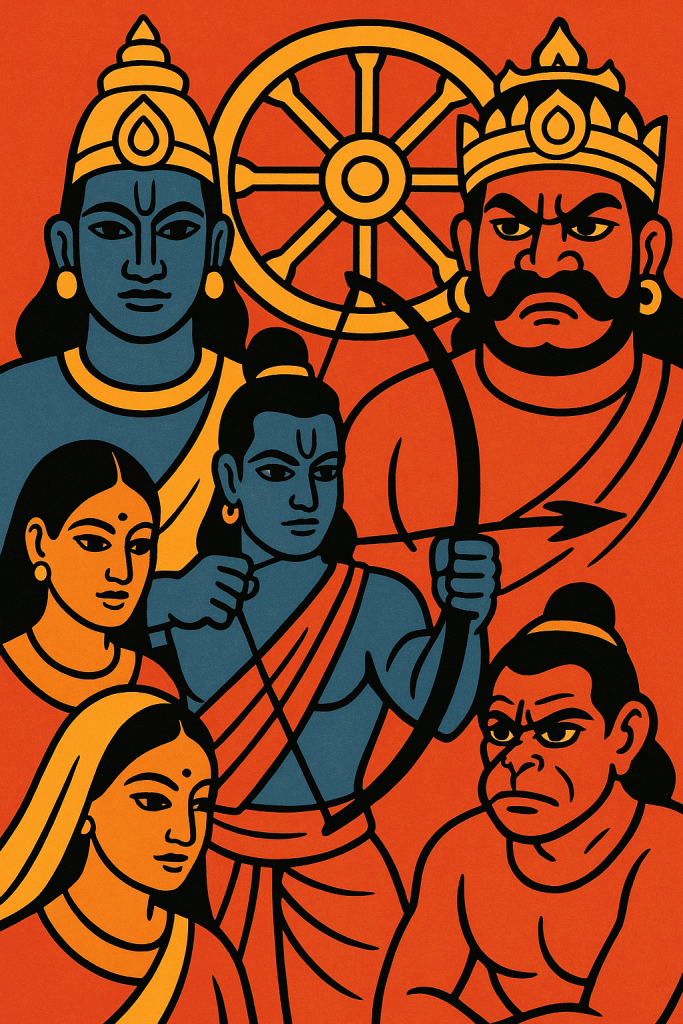

Rama is devastated. He and Laksmana begin a search for her and come across a few more interesting characters before learning that the king of the monkeys (not king Louie but possibly the root of his inspiration) may be able to help. You read that correctly. There’s an underground monkey kingdom and a tribe of militant bears in this story. Have you ordered your copy yet?

It turns out the monkey kingdom has endured its own dynastic drama. The original king Vali went missing for a year. His younger brother Sugriva served as a faithful regent after months of failed searching for Vali. Later, after Vali finally returned he unjustly assumed his brother had usurped his throne so he fights and exiles him. Vali also took Sugriva’s wife as his own. You read that right: a dynastic struggle, a king in exile, and a stolen wife. Why not have the human drama recapitulated in the monkey world? Sugriva is joined in exile by only one follower named Hanuman who is the Spider-Man of this story. He’s an intrepid hero, has a great blend of duty, honor, bombast, and daring, with a healthy dose of cheekiness that makes him a much beloved character who apparently finds his way into lots other stories after the Ramayana. He provides great comic relief among a cast of intense and earnest players.

Rama makes one of the most controversial decisions in the story when he joins forces with Sugriva and kills Vali from under cover while he’s engaged in one on one combat with his brother. Once on the throne Sugriva promises to put the resources of the monkey kingdom at Rama’s disposal to find Sita.

There’s also a time element that comes to the forefront here. Bharata has promised to step down as king when Rama returns from exile after 14 years. He as vowed that exactly 14 years and 1 day after Rama left, if the true king has not regained his throne, he’ll immolate himself. A bit extreme? Yes. Does it provide excellent dramatic tension? Also yes. Bharata has given us no reason to doubt his commitment. To make sure his brother doesn’t kill himself and leave Kosala leaderless, Rama needs to get home in less than a year. After 13 years of a pretty vague timeline, the narrative gives consistent time posts over this final year. I wrote “tick-tock” in the margin many times after Sita was abducted. Unfortunately, just as Sugriva regains the throne the monsoons begin and no search can be undertaken. Rama must wait. For months. Tick-tock.

After the rains stop there’s some more time-sucking drama in the monkey kingdom, so as the search finally gets underway, with the help of the tribe of bears, we really are in crunch time. The entire subcontinent is searched, and Sita cannot be located. Hanuman has a hunch that she must be in Lanka. That is, after all, where Ravana lives. Hanuman jumps, literally takes a single enormous leap, across the channel and sure enough he locates the lost queen. He is captured but makes a harrowing escape to report his find.

Deliverance

An army of monkeys and bears is gathered and an amphibious assault leads to a siege of Ravana’s golden palace. The war section is a great examination of Ravana’s character and the corrupting influence of power and the idiocy of sycophancy. While there is some drama, this is epic poetry, it’s a superhero story not tragedy, and the good guys win.

In the Buck retelling, and I’m assured this is not an invention of his own but a feature of several texts, there is a surprise twist / reveal about Ravana. A Dr. Strange in Infinity War and End Game vibe. Ravana was actually trying to be killed (released from Samsara) all along and during his transcendental meditation days he learned this was the way to make it happen. To be honest it feels like retcon to me. It undermines the moral vision of the story so I’m gonna ignore it.

Ultimately, Rama and Sita are reunited and there is a joyful and triumphant return of the king at Kosala. Rama reigns in peace and prosperity for thousands of years.

This isn’t quite the end. There’s an epilogue that is also quite controversial and also out of character with the remainder of the story. This epilogue conveniently brings the action full-circle to the beginning when Sita and her sons are banished to the forest where Valmiki has just been awakened from his slumber in the termite mound. I may or may not offer my take on this section. It feels like Book 24 of The Odyssey. I don’t like it, but a properly motivated reader can still interpret it in a profitable way.

That’s the story. Simple enough that the universally appealing hero’s journey is easily identifiable, but rich and complex enough to feel new and different. The framework offers many plot driven examinations and discussions of character, virtue, and piety. Exactly what one wants in an epic. I really enjoyed it and filled the margins of my copy with notes and ideas.

In my next journals we’ll dig into specific characters and interactions and what we learn from them.