If I recall correctly this question intrigued viewers of the popular American television show Lost about 20 years ago. I was a late arrival to the series, and never bothered to watch the first half, nor did I think too closely about the contents of the series following its conclusion, but it seemed like a fun way to start my journals on the ancient Hindu epic The Ramayana. Ultimately I hope to have two series on Indian epic. One on the Ramayana (this one), and one on the Mahabharata/Bhagavad Gita. The vast majority of my journaling has been focused upon ancient Greece/Athens whose culture and influence are relatively familiar to modern Americans, so I tried to limit my discussion of general background information in those essays. I suspect most western readers will know less about the cultural background of these texts, so some context will be beneficial. I will say here that I don’t consider myself to be very knowledgeable. Most of what I share on Indian History, Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism will come from a few “Great Courses” series on the History of India, The Silk Road, Religions of The Axial Age, Hinduism, and Buddhism that I’ve tried to absorb through repeated listenings over the past few years. I’ve also read commentaries accompanying the texts I’ll use, and performed many Google searches on specific topics. I’ve never been to India or sat down to discuss these ideas with believers or practitioners of Hinduism. I’m probably at the worst possible spot on the Dunning-Kruger curve.

In my experience “outsiders” frequently mix up historical facts, and misunderstand many doctrinal and cultural details of the faith tradition in which I was raised, so I suspect I might do the same here, but any misrepresentations will be unintentional. My goal is to neither promote nor defame any of the belief systems I examine. These journals are intended as a personal exploration and not a definitive representation or critique of Hinduism as believed, practiced, or lived over the past 3000 years. Hopefully my errors will not be too egregious or offensive.

With that said in this specific journal my primary goal is to introduce the general/historical concepts relative to The Ramayana. To do that I think a brief discussion of Vedic religion, and some of the faith traditions which emerged in India in the first millennium BCE which share dharma as a doctrinal concept is appropriate. Next, I think a brief discussion of the concept of henotheism is necessary to situate the Ramayana within this greater religious and cultural context. Warning: I won’t actually discuss the story or get too deep into the concept of dharma as presented in the text in this journal. The outline I’m working from right now schedules a plot summary for the second installation in the series with my discussion of dharma and a more detailed textual examination occupying the 3rd and 4th essays. There may or may not be a 5th piece which is conceptually vague at present.

A Wildly Incomplete History of the Subcontinent

In my high school world history textbook, World History: People and Nations, the one whose cover was dominated by a photograph of the Tutankhaman’s sarcophagus, had something like 5 paragraphs on what I believe it called “The Indus Valley Civilization”. After a lengthy discussion comparing and contrasting Egypt and The Nile with Mesopotamia and Tigris/Euphrates cultures, the editors mentioned that other river valley civilizations also existed in India and China. The limited information and discussion in the book may have something to do with the Indus Valley culture’s relatively late discovery by the west and the fact that we still cannot translate its writing. There may or may not be an element of servicing a specific narrative of world history as a westward facing progression which finds its acme in the powerful modern nation state whose children the textbook was written to educate. Bottom Line: In the narrative I managed to assemble from high school, India made a brief appearance in Alexander of Macedonia’s campaigns and the Silk Road, but was only “really” introduced to the discussion when the Portuguese and British East India Company show up. Consequently, a background understanding of India and its religious traditions wasn’t really part of my formal education. It’s actually pretty embarrassing because some of my best friends growing up came from families who had immigrated from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, including my next door neighbor, but teenagers don’t often talk about cultural heritage while playing basketball so I remained mostly ignorant.

Let’s Talk Ancient History

Indus Valley Culture is sometimes called Harappan culture due to the fact that the wider world became aware of its existence when scouting parties for the British East India company looking into troop transport via the Indus River encountered exposed walls of an abandoned settlement near the modern city of Harappa. Eventually, an entity called The Architectural Survey of India led the first organized excavation of not only Harappa, but Mohenjo-Daro and several others. The remains of large, well organized cities constructed with uniform brick, paved thoroughfares, and impressive plumbing systems are located in the Punjab province of what is now Pakistan.

Evidence suggests human habitation and cultural development in the area existed as early as 6500 BCE, but the generally accepted dates of Harrapan culture are 3000 – 1300 BCE. Interestingly, this situates its decline slightly before the eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age collapse, I haven’t dug into any potential connections there, but there is evidence of trade with Mesopotamia at this time. The decline of Indus Valley culture appears to coincide with at least two changes: a change in the course/ flow of the Indus river, and the arrival of Aryan nomads from the central Asian steppe.

Were the Indus Valley residents displaced, conquered, or simply absorbed by the arrival of this new culture? Nobody really knows. Nomads of the central Asian steppe have a well documented history of conquest and disruption of sedentary civilizations: think Atilla the Hun and Ghengis Khan. This history is in part why Adolf Hitler declared Aryans “the master race”. A survey of the overall history of central Asian nomads tells a story with a wide variety of social interactions with other civilizations, so the equation of nomad with disruptive, conquering, barbarian is an oversimplification, but that’s a discussion for another day. The debate over the fate of the Indus Valley culture and the relationship between nomadic migrants and the established inhabitants of the subcontinent in the first and second millennium BCE is an open question and the available information illustrates the importance of examining actual data rather than imposing our own biases. The idea of an “Aryan Conquest” of the area was postulated by a white European dude in 1953, but the available genetic, cultural, and archeological records tell a more complex story. Why am I bothering with this question? Because of The Vedas.

The Vedas And Why They Matter

One thing we do know is that the new arrivals brought with them a written language which has come down to us as Sanskrit. Sanskrit is an Indo-European language, so called because it shares word roots and structures with an enormous number of other languages spanning from Scandinavia through the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and all the way to the Indian Subcontinent. The theory goes that all of these languages have roots in a “proto-indo-european“ language and therefore that Sanskrit must have arrived with migrants from Central Asia and that a record maintained in their language must reflect, at least in part, their culture and influence upon their new home. This postulated “original” language implies that descendants of Proto-Indo European speakers either settled, conquered, or wielded cultural influence over an enormous swath of territory extending from Scandinavia to the Indian Ocean. In Sanskrit the term these people used for themselves was “Aryans” meaning noble ones, and thus we see the origin of Hilter’s claim that Aryans were a “master race”. See paragraph above for data which undermines this belief.

Returning to why Aryan migration and Sanskrit matter for our purposes. The oldest of the extant written records in Sanskrit are the Vedas and they bear a striking resemblance to Irano-Aryan Avestan writings. While the Vedas don’t explicitly discuss an “invasion” or “conquest”, there are discussions of migration that are consistent with entry to the subcontinent from central asia. The oldest of the vedas is the Rig Veda, a collection of 10,000 mantras / hymns which contain a mixture of cosmology, theology, morality, and ritual. I haven’t read much of The Vedas (as a collection they’re substantially longer than the Bible), but the enduring cultural power of this scriptural canon that is arguably the oldest extant collection of sacred writings that are still in active use is impressive.

One of the most obvious examples of their enduring influence is found in the Purusha-Sukta or “Hymn of Man”. It is one of several creation stories in the Vedas and it involves the gods dismembering a cosmic giant referred to as “The Man”. In it we read, “All creatures are quarters of him; three quarters are what is immortal in heaven… and one quarter of him still remains here. From this he spread out in all directions, into that which eats and that which does not… Horses were born from it… cows were born from it, and from it goats and sheep were born.”

This sort of creation from a dismembered sacrificial supernatural being is found elsewhere. The other examples which come immediately to mind are the Mesopotamian creation myth (Enuma Elish) in which Marduk creates the world from the body of the slain dragon Tiamat who is also his great-great- grandmother. There is also the Norse myth of creation by and through Ymir. Chinese legend features Pangu and the Aztecs have Tlaltecuhtli.

Here’s one part that should catch our attention, “When they divided The Man, into how many parts did they apportion him? What do they call his mouth, his two arms, and thighs and feet? His mouth became the Brahmin; his arms were made into the Warrior, his thighs the People, and from his feet the Servants were born.” This is the creation of the four Varnas. This division of humanity is cited as the basis for India’s historic caste system.

There is debate about the difference between Varna and Caste, and one way of understanding the distinction is that Varna is the theological doctrine, and Caste is the lived social reality. This type of division enforced as religious orthodoxy has an obvious potential for structural social inequality. Modern India has “reservations” that is to say reserved educational career opportunities for “scheduled castes” in an effort to address this reality founded upon thousands of years of tradition. This concept is so pervasive Seattle has passed, and the State of California has considered, anti-discrimination laws because of the large number of Indian immigrants who work in the U.S. technology sector. I’m going to avoid a digression into how this belief compares with theologically based social orders in other cultures and religions (3 estates in medieval Europe), or the chicken/egg question of religious text as source of, versus ex post facto support for existing cultural practices, but it is interesting to note that the influence of this specific belief continues to exert so much direct influence on the lives of over a billion people. I will take a moment to note that the protagonist of The Ramayana, Rama, is a member of the Kshatriya (warrior / arms) class.

Another important feature of the Parusha mantra is the connection between creation and sacrifice. The universe and everything in it came about through ritual sacrifice. There are a lot of ways a religion could go with a story like this. The most gruesome I can imagine is an adoption of human sacrifice that explicitly recapitulates this story as a way of maintaining cosmic order. I am unaware of evidence for this in Vedic religion. I have no idea if the story of Tlaltecuhtli is connected to the Aztec ritual of human sacrifice. One apparent takeaway in Vedic religion was the idea that sacrifices by humans were necessary to sustain cosmic order.

Apparently a doctrine evolved that sacrifice was not merely a symbolic act of devotion, but efficacious in its own right. That is to say that there was genuine power wielded by the officiant that actually upheld the makeup of the cosmos. Think about the distinction between Christian doctrines on the Eucharist. Most protestant faiths view the elements of the ritual as symbolic representations of the body and blood of Jesus. The Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation holds that the bread and wine actually become his flesh and blood. There’s genuine, world altering, supernatural power implied there. If the ritual rises beyond the symbolic in this way, then it stands to reason that authority, expertise, and exactness in its performance would be of paramount importance. It should come as no surprise that the priestly Brahmin caste “the mouth” of the cosmic giant became the only ones who could perform the rituals that upheld cosmic order and brought blessings like fertility, health, bounteous harvests, and success in business and war. The result appears to be a rigidity or ossification of Vedic religion as performative. Regardless of the validity of a theology or lack thereof, I think ritual has psychological power and has a place in human life, but I think we are all aware of the risks that accompany rigidity. There’s a reason the word “stale” so often precedes “ritual” in modern discourse.

The Axial Age

In 1949 Karl Jaspers, a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher, coined the term “Axial Age” to describe widespread changes in human philosophical and religious thought between 8th and 3rd centuries BCE. This timespan accounts for Homer, the Athenian tragedians, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle in Greece, the Analects of Confucius and The Dao De Jing in China, Zarathustra and Zoroastrianism in Persia, and relevant to our discussion, the emergence of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism in India. There is a lot of variety within this group, so to suggest that Axial Age religions represent a specific school of thought or approach would be erroneous. Indeed one of the critiques of the concept of The Axial Age is the lack of unity of thought on offer. As I understand it, the argument in favor of an Axial Age is that the unifying theme is the change to which questions religions and philosophy are responding.

Pre-axial religions often focus on questions of etiology and process. What is the origin of the cosmos, life on Earth, and humanity specifically? How do we ensure fertility, and prosperity? Consider the first dozen chapters of Genesis. We get creation in chapters 1&2 (where do we come from?), the fall and exile of Adam and Eve in chapter 3 (why are we here?), murder and punishment in chapter 4 (justice and order), the Noachian deluge in chapters 5-9 (etiology of natural disasters as divine wrath), a multiplicity of languages chapter 11 (why do different peoples exist?), a justification for social stratification and slavery in chapter 9, and finally a recipe for how to make peace with God to ensure future generations, a homeland, and prosperity (fertility) in chapter 12. When we read other ancient texts like the Enuma Elish, the Egyptian Book of The Dead, and The Vedas similar questions are entertained and a common theme is that success derives from obedience to the natural order and the gods. Alignment with these supernatural forces was primarily accomplished by ritual and sacrifice (Genesis 22, 31, Exodus 12, Leviticus etc.) This association between successful human endeavor and ritual went beyond the individual and household and applied to the state. The Chinese Mandate of Tian, the Egyptian Ma’at offering and Sed ritual, and Mesopotamian Ekitu festival all connected the health of the nation to the cosmic order. Consider the Passover in the context of the Exodus. In the gods they trusted.

Returning once again to the Purusha Mantra: When the cosmic man was sacrificed, a lot more was created than just the four varnas:

“the moon was born from his mind; from his eye the sun was born. Indra (The Sky God) and Agni (God of Fire) came from his mouth, and from his vital breath, the Wind (also a god) was born. From his navel the middle realm of space arose; from his head, the sky evolved. From his two feet came the Earth, and the quarters of the sky from his ear. Thus they set the worlds in order… With the sacrifice the gods sacrificed to the sacrifice.”

From this we learn not only was the sacrifice of the cosmic man the source of humans, plants and animals, but the entire universe and the gods themselves. How the gods created themselves through the sacrifice of something greater than the universe itself is beyond me, but the idea that there is an order to the cosmos mediated through sacrifice could and was easily extended to the rituals performed by the priestly Brahmin class. Religion as described in the Rig Veda fits well within the Pre-Axial category. There’s even a specific term used in The Vedas for the actions (sacrifices and rituals) which uphold cosmic order: Dharma.

The Axial Age didn’t abandon the connection between humans, divine order, and the cosmos as subjects of religion, but the existential questions beyond survival received greater emphasis. Religions and philosophies of the Axial Age place the questions of ethics and morals, how we relate to one another, and the search for meaning and purpose within the context of the “true” nature of reality front and center. The Analects of Confucius aim to achieve peace, order, and harmony by teaching the duty of the individual to cut, grind, and polish one’s life like a precious stone. Plato pondered the creation of a just city as a macrocosm of a just and reflective life in The Republic. Aristotle argued that Eudaemonia, a fulfilling, thriving, joyful life in a polis as the greatest good and a result of individual moral behavior in The Nicomachean Ethics. Zarathustra transformed the project of cosmic maintenance into an individual and collective struggle between good and evil, and in the process gave rise to Zoroastrianism. Abrahamic tradition is a bit more difficult to pin down because The Hebrew Bible, even the Torah, seems to have been consolidated within what is generally considered The Axial age, but many readers notice that Leviticus, the exilic prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah, and The Sermon on The Mount emphasize different conceptions of and relationships between worship, individual behavior, order, and social justice.

Post-Axial India

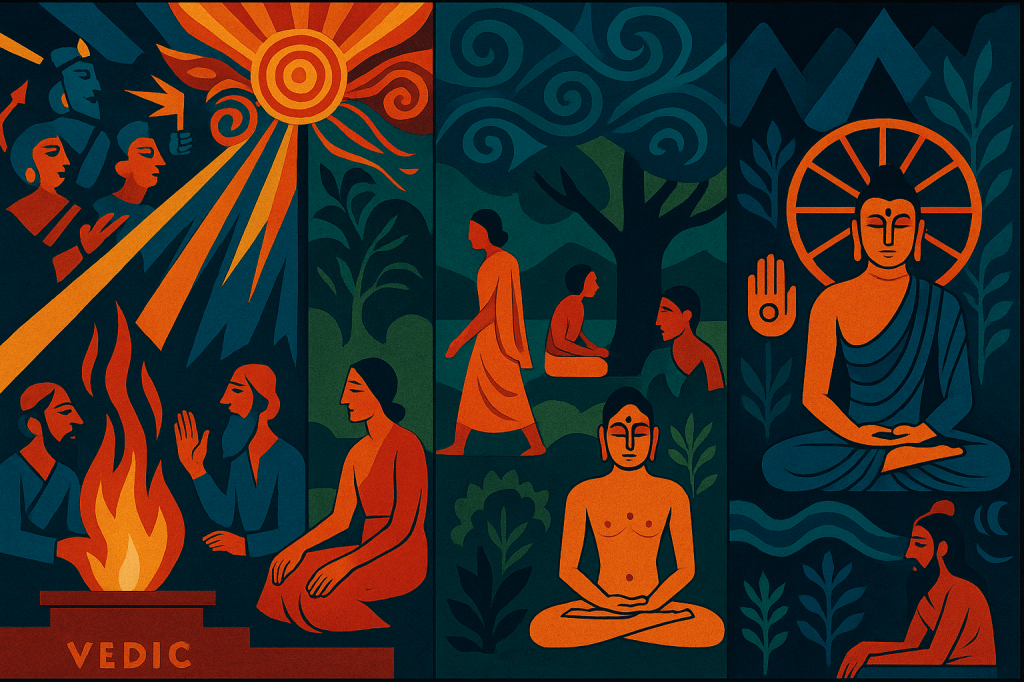

It seems reasonable to observe that each culture, religion, and philosophical school inherited its own pre-axial traditions and beliefs. It is no surprise that the specific questions and responses developed during this time also differ from place to place. When inheritors of the Vedic tradition asked themselves about meaning, morality, and the nature of reality there was an impressive blossoming. Three of the traditions developed in axial age India remain extant today: Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. All three inherited a suite of beliefs that shaped their theology as either a springboard to expansion or a sounding board for refinement or rejection.

Vedic religion features an impressive pantheon of gods. Are humans simply their playthings, their servants, or their fellow travelers? The shared doctrines of samsara, maya, karma, moksha, and dharma are also refined or redefined in this divergence. Samsara is generally accepted as the idea that life is a place of confusion and suffering because we fail to appreciate the ultimate reality of existence. A major contributor to our confusion and suffering is Maya, the illusion created by sense, misperception, and misconception that drive behaviors incongruent with what is real and good. The doctrine of transmigration of the soul, the idea that we are continually reborn into forms contingent upon our prior deeds because we fail to see and act in accordance with the reality of the cosmos is popularly known as reincarnation. The form into which the soul is reborn is determined by an unflinching application of retributive justice we call Karma. Karma inexorably follows us through our journey and offers a response to the question of inequity and evil. Why do we suffer even when we seem innocent of any offense? One can trust that we are reaping the fruits of past actions, perhaps from another life. Reincarnation isn’t seen as a good or desirable thing. It is true that rebirth is a return to existence, but we return to the Samsaric realm of confusion and suffering. This is a less than ideal outcome. These shares concepts offer obvious positions from which to ask questions about the exact nature and meaning of existence, and the purposes of ritual, sacrifice, and moral behavior.

How does one see past Maya to the genuine reality? How do we behave to maximize good Karma and minimize the bad? Are we doomed to an endless cycle of suffering and rebirth? The escape from Samsara and release from confusion and suffering is known as Moksha in Hinduism and Nirvana in Buddhism. How exactly does one escape? What happens after that? Alongside these concerns about the nature of existence, and our role in it, the concept of Dharma transforms from the rituals and sacrifices that literally uphold the cosmos, to something related to the insights about the true nature of reality and the behaviors and practices that help one depart samsara. I feel like an appreciation of this inherited framework is useful when exploring Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. They all offer unique insights, sometimes they contradict one another or reject specific ideas, but they all respond to this shared inheritance.

From my perspective, and this is based on a very limited understanding of these traditions: Jainism seems to have adopted the virtues of justice and purity as the primary foci of belief and behavior. The Jain doctrine of Ahimsa, non-violence, and practices like sweeping the ground before one takes a step to avoid harming even an insect, and wearing a face mask to prevent inhaling a living creature, renouncing clothing due to the harm imposed on living things in their manufacture, and in the extreme, refusing food and starving to death so that no other living thing is harmed to perpetuate one’s own existence are all markers of this commitment. Forms of Asceticism are found in all three religions, but the doctrines of Jainism point most clearly toward this path.

In the Upanishads, the final additions to the Vedic cannon, the idea that the individual “self” known as Ahtman, was in fact identical to the ultimate cosmic reality known as Bruhmin, was presented as a key understanding of the true nature of reality. Buddhism adopts its own version of this belief, Sunyata (emptiness), and presents the claim that ignorance and confusion about the nature of reality leads to aversion and desire which in turn produce unnecessary suffering in life. The Buddha taught mindfulness and the middle path as means to liberation without resorting to asceticism.

Jainism and Buddhism have specific points of origin and have semi-historic founders: Mahavira for Jainism, and Siddhartha Gautama for Buddhism. Technically Mahavira is believed to have restored eternal truths to a new age, but you get the point. One generally accepted definition for dharma in both traditions is the corpus of teachings of the founder/restorer. The section of the Pali canon known as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta which is allegedly the Buddha’s first public teaching after his own awakening literally translates as “setting in motion the wheel of dharma”.

What about Hinduism? Hinduism departs the least from traditional Vedic religion and modern Hindus continue to regard the Vedas as scripture. However, tremendous diversity of thought and belief has developed within Hinduism over the past 3000 years. During the Axial Age The Upanishads and several Hindu Epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata were composed and are thought to reflect evolutions in philosophical focus over time. One of the primary changes seen in this era is the democratization of ritual practice. As noted above, traditional Vedic beliefs demanded exact performance reserved to trained Brahmin priests. In Axial Age Hinduism the individual was empowered to pursue not only devotion and worship but to engage in rituals and sacrifices. There’s a revealing passage in the Ramayana which describes the religious environment of the kingdom ruled by Rama’s future father-in-law, “there were no pretentious Brahmana of priests in Videha. Long before Janaka (Rama’s future father-in-law) got rid of them. First they told him he needed them to make offerings to the little gods, so Janaka broke all the statues of the lesser gods. Then the priests said that anything a man did for himself trying to find the True was wrong and useless and only they knew all the answers. Janaka didn’t argue. He put a heavy curse on them, their heads fell off, and the brittle bones were stolen by thieves“. Yikes. Talk about cutting out the middleman. Janaka performs the marriage of Rama and Sita himself. Later in the Ramayana King Drasaratha dies while Rama is in exile and his brother Bharata performs the cremation and funerary rites and no mention of a priest is made. This democratization is not the only change in axial age Hinduism, nor is it unique to the tradition, but it is one of the clear practical departures which set it apart from traditional Vedic practice. This change suggests two questions to my mind. If one conception of Dharma was the power of ritual and sacrifice to uphold the order of the universe, does this liberalization imply a change in that concept as well? If so, how?

What about the gods? Jainism is considered a transtheistic religion, which means that the cosmos exists independent of a supreme being. There are powerful “supernatural” beings with good and evil character, but they, like humans, are also created, live, and die and are therefore different from the immortal gods of the Greco-Roman pantheon or Abrahamic conception of a transcendental God. Modern Buddhist traditions run a gamut of conceptions of deity, however I’m led to believe that parts of the Pali Canon (the oldest Buddhist texts) suggest that the gods may exist, and may be more long-lived and powerful than humans, but they are trapped in the same cycle of death and rebirth in the realm of Samsara, therefore worshipping them is not a viable path to liberation.

Henotheism and Lord Vishnu

The pantheon of Hinduism is famously unwieldy. The traditional number of Hindu gods is 330,000,000. While it’s widely accepted that this number is not an actual account of deities, it expresses the idea that there are an astounding number and variety of manifestations of the divine. How does one offer appropriate devotion when there are so many possible gods? How does one know if one is worshipping or seeking the aid of the correct god? Can one please all the gods, or does the worship of one bring a human into conflict with another? Questions like these are frequently encountered when dealing with Greco-Roman Olympians. The plots of the Homeric epics are partially driven by these types of conflicts. The tragedy of Hippolytus is a harrowing cautionary tale. Avoiding these types of problems is an obvious potential advantage of transtheism and monotheism.

One way of navigating potential conflicts of polytheism is henotheism, the idea that one can choose to worship a specific god as supreme within a pantheon. An obvious example of this can be seen in Stoicism and the identification of The Logos as a supreme rational intelligence. Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus all discuss how one finds peace when one aligns one’s mind and will with “God” in the The Logos. Some may recognize the clever co-optation of this idea in the Gospel of John. The most controversial example I can think of is the archeological evidence that Elohim (a plural Hebrew word for gods and deity) may have come to be synonymous with Yahweh by singling out the Canaanite god El as the supreme god within that ancient pantheon. As far as I can tell the evidence for this is minimal and the idea is mostly conjecture.

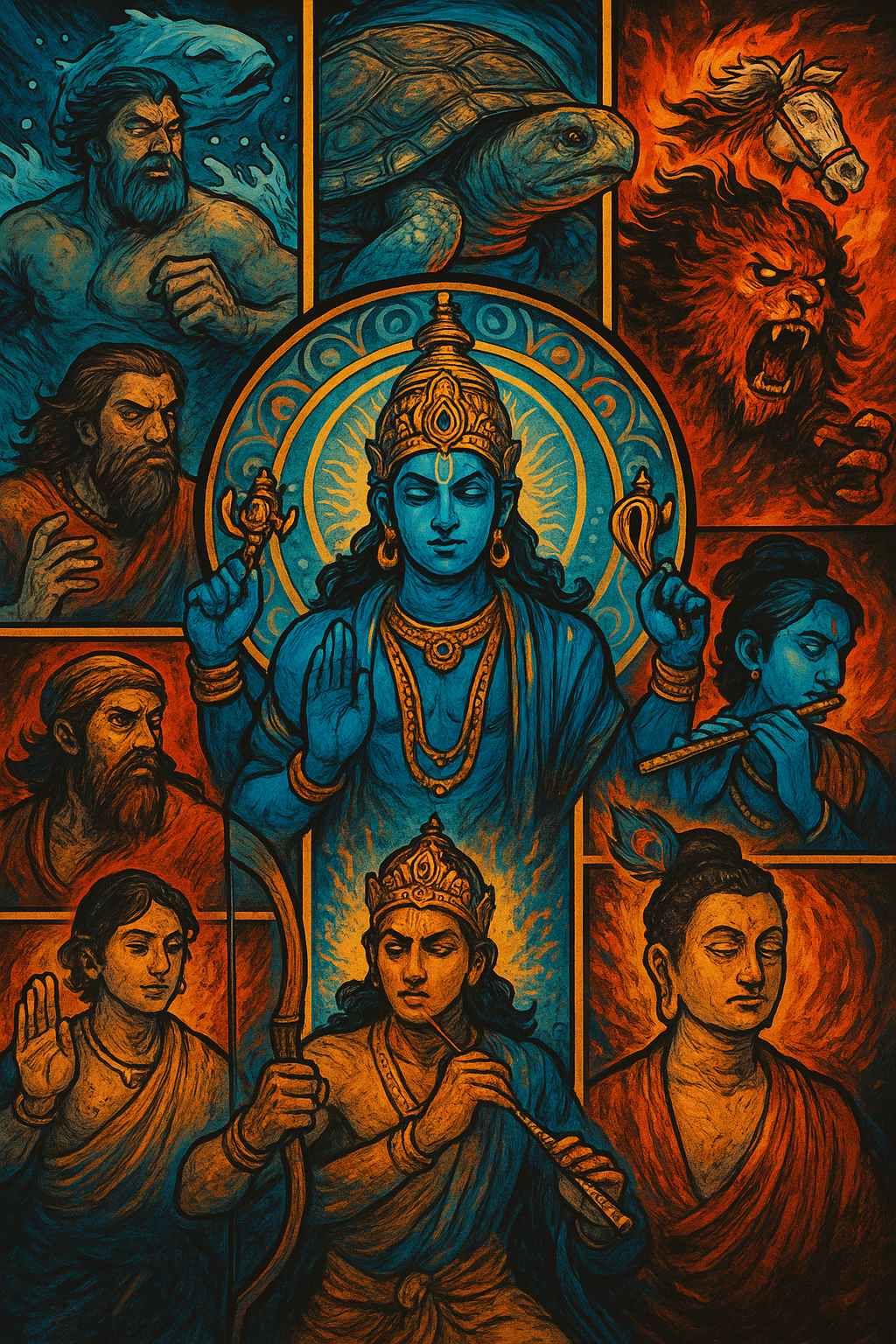

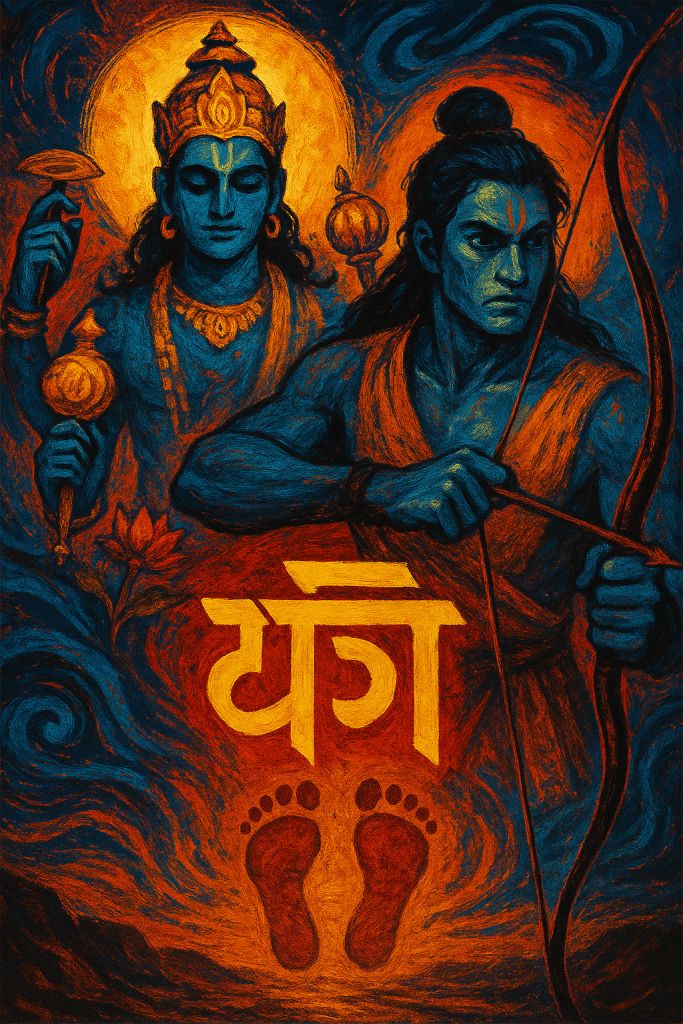

In Hinduism henotheism was not a stepping stone to monotheism, but a reflection of a personal decision to adopt a specific god as the focus of one’s devotion and practice. It’s acceptability can be easily reconciled with the claim that the individual “self”, including the selfhood of the gods, is the same as ultimate reality. The Ahtman/Bruhmin thing from the Upanishads. Anyway, some Hindus worship Shiva, the god of destruction and restoration. This tradition is known as Shaivism. Ganaptya recognizes Ganesha, the elephant-headed remover of obstacles, as foremost. Shaktism focuses on the divine feminine. As far as I can tell these traditions don’t represent distinct or competing orthodoxies, but are simply accepted expressions of faith and devotion. According to a 2020 poll conducted by Boston University, Vaishnavism, the worship of Vishnu, the god of preservation and order, with nearly 400 million adherents, is the largest of these subsets of Hinduism. It is into this specific tradition that we step when reading the Ramayana. The protagonist of the Ramayana, Prince Rama, is the seventh avatar (incarnation) of Vishnu on Earth. Consequently, The Ramayana isn’t just a great story, but represents something like a “gospel” in that it details the life of a god on Earth in mortal form. Because Vishnu is the god of Dharma one can reasonably interpret the words and actions of Rama as reflecting this principle. It is in this vein that I will examine the story.

A Note On The Translation

Finally, the question of translation is a concern anytime I read a foreign text. The famous Italian saying “translation is treason” (Can one actually trust this anglicization of “traduttorre, traditore”? Winking emoji) is invoked frequently. Language and culture go hand in hand, so even a faithful literal translation is unlikely to capture the full import and nuance of a cultural touchstone. Further complicating the question of an ancient text and this one in particular is: which one? Stories are meant to be shared and historically the most efficient and enjoyable way of doing so is through oral performance. Storytellers, audiences, and cultural demands all change, consequently so does the story. The Ramayana has been very popular throughout South and East Asia for thousands of years from what is now modern Pakistan to Indonesia. It turns out there are many different versions of the Ramayana, so deciding which one to read is a legitimate question. In a culture saturated with advertising, AI deep fakes, and imitation we crave authenticity. We want the genuine article. I couldn’t help but want to read a well regarded translation of the oldest or best known version. As far as I can tell this exists. Bibek Debroy’s translation is widely respected. It’s also 1400 pages and comes as a 3 volume set. A tribute to how much I enjoyed this story, I’ve been tempted to read his or some of the other modern English translations that typically run to around 1000 pages. There’s one by Arshia Sattar that is also well regarded. Robert Goldman’s work is hailed for fidelity, readability, and scholarship. So why, with all these options, would I choose to read a translation made in the 1960s by a son of a US Congressman and heir to a brewery fortune from Lake Tahoe? The honest answer is that it was the shortest of the bunch. With that said I don’t regret it. The internet doesn’t seem to know much about William Buck except that he stumbled upon the Bhagavad Gita in the Nevada State Library and fell in love. He decided to learn Sanskrit and make translations of several classical Hindu epics. One oft repeated story is that he fronted an Indian publisher the cost to print an 11 volume version of the Mahabharata in Sanskrit so that he could have access to it. He eventually published what he termed “retellings” of both the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Clearly these aren’t complete or literal translations as they’re significantly shorter than others. Having read another retelling by the Indian author RK Narayan which is under 200 pages, I will say Buck’s version offers significantly more detail while keeping a brisk pace. I think the writing is generally lucid and enjoyable, and some parts are beautiful and poetic. From commentaries about the Ramayana I’ve encountered I don’t feel like Buck’s version deprives the reader of any major features of the original. In short it feels like an acceptable entry point. Long enough to demand commitment and deliver an immersive experience to the reader, but short and accessible enough that it won’t intimidate someone possessed of only a moderate curiosity.

That being said I read the shorter Narayan version first and enjoyed it, but I knew I was being deprived of details and potential insights. Reading Buck’s version paid off that impression. Consequently I can’t help but wonder what I’m missing by not pursuing an unabridged translation. How would knowing “the real story” change my thoughts? I suspect I’ll revisit the Indian epics and maybe I’ll find out someday, but I’m a slow reader and I’ve got a lot of things I want to get to so committing myself to thousands of pages up front was not in the cards. To be clear my goal is not a survey of religious orthodoxy, but an exploration of what I learn from my own experience reading so getting too bogged down into which version to read doesn’t really further my goals anyway. I try to appreciate the cultural context to help me enjoy and extract more from the experience, but to a certain degree the “authority” of a text is irrelevant.

Additionally, the fact is this story has been retold many times for people in many lands and cultures for over 3000 years. I think it would be inappropriate to say that the Tamil, Jain, Buddhist, Burmese, Nepali, Cambodian, Malaysian, Filipino, or Indonesian versions are somehow of less value or validity just because they are different or newer than the oldest available Sanskrit text. Similarly a retelling that has been crafted to speak to a modern English speaking audience is not an inherently invalid version. I will admit that if I were to claim that I am offering a fully informed opinion on Valmiki (the composer to whom the Ramayana is attributed), Vaishnavism, or Hinduism, then using only a 20th century American English abridgment as a proof text would be irresponsible. Consequently, I will refrain from doing so. Therefore, as I discuss the concept of Dharma, and interpret the text I will try to be mindful that the story comes from the cultural context I’ve described above, but that the version I’m reading was written by someone who, as a modern American male, likely shares many of my blindspots and biases. Lastly, I realize I’m attempting to elucidate an abstract religious/moral concept using a fictional source and splitting hairs about authoritative texts seems a bit much, but I feel it’s appropriate to be sensitive to communities when discussing matters of belief, faith, religion and holy texts. I’m a believer in the value of myth independent of claims to objective reality/historicity, but historically I have felt misrepresented by others claiming to explain Mormonism, so it seems hypocritical to be oblivious to how I approach other faith traditions.

Hopefully these bits of historical and cultural context will make my discussion of Rama and his adventures more relatable and enjoyable. Next up, my own brief retelling of the Ramayana. The goal here is to make it so that when I start discussing my observations that the names and quotes will have some meaning for the reader.