Ever notice how metaphors for revenge involve food and taste? Sweet revenge. Revenge is a dish best served cold. Maybe this has something to do with the concept of revenge appealing to a deep desire or appetite within us? If you’ve been wronged there’s something inside that wants to settle the score. While the actual content was far more nuanced than the conventional wisdom on the subject, EVERYBODY knows Hamurabi’s code says “eye for an eye, and tooth for a tooth”.

Anyone who maims another shall suffer the same injury in return: fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; the injury inflicted is the injury to be suffered. One who kills an animal shall make restitution for it, but one who kills a human being shall be put to death. (Leviticus 24:19-21)

Consider the timeless appeal of The Count of Monte Cristo, and Stephen King’s retelling Rita Heyworth And The Shawshank Redemption. There is a simple and satisfying logic to reciprocity. Harm me and you’ll be repaid with the same harm. Balance the karmic scale. By definition the punishment fits the crime.

In Libation Bearers Elektra momentarily pauses before praying for revenge at her father’s grave, “How can I ask the gods for that and keep my conscience clear?”

The leader of the women who accompany her, the chorus of this play, replies, “How not, and pay the enemy back in kind?” (123-126 Fagles)

Elektra then prays, “Raise up your avenger, into the light, my father- kill the killers in return, with justice! So in the midst of prayers for good I place the curse for them. Bring up your blessings, up into the air, led by the gods and Earth and all the rights that bring us triumph.” (148-153 Fagles)

“Mighty Destines come, fulfill the will of Zeus, Justice veer the course, words of hate fulfill hateful words. Justice screams and demands her price. Bloody blow pays bloody blow. ‘The doer suffers’, sounds the saying, three times old.” (306-314 Meineck)

“Justice turns the wheel. ‘Word for word, curse for curse be born now’, Justice thunder, hungry for retribution, ‘strokes for bloody stroke be paid. The one who acts must suffer.’ Three generations strong the word resounds.” (315-321 Fagles)

Clearly the principles of retribution are the modus operandi of the citizens of Argos.

There are multiple stories for the origin of the Furies, but there’s one I like best. You’re probably aware that Zeus became king of the gods when he overthrew his father Kronos. It turns out that a generation before Kronos had overthrown his own father Ouranos. Ouranos, the sky, really had a thing for Gaia, the Earth, and covered her up. Their close proximity inevitably resulted in reproduction and Ouranos did all he could to keep this next generation under wraps. Gaia wanted a bit of breathing room and for her children to thrive, so she conspired with her son Kronos and the outcome was that Ouranos was castrated. The business of intergenerational violence thing gets started early in Greek mythology. Kronos hurled Ouranos’ genitals across the world and as they flew blood and semen dripped out and fell to the ground. Famously, Aphrodite emerged from the waves when semen hit the sea off the coast of Cythera. When the blood hit the ground The Furies emerged and have been demanding vengeance ever since. The point of this graphic digression is to help us appreciate the story that informs the Greek audience witnessing The Oresteia. The Furies are very much an embodiment of retributive justice spontaneously sprouting up from the Earth itself in response to domestic violence.

Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him.

Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?”

He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?”

And the Lord said, “What have you done? Listen, your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground! (Genesis 4:8-10 NRSV)

Blood crying out from the ground. It’s a powerful image.

The point is that not only does retribution scratch an itch inside us. Not only does it have a satisfyingly simple symmetry of cause and effect, but here we have multiple cases where it is almost a part of nature and enjoys a form of divine sanction.

Additionally, in theory, the transparency of the system acts as a deterrent to crime. The Furies make the argument with these words:

There is a time when terror helps, the watchman must stand guard upon the heart. It helps, at times, to suffer into truth. Is there a man who knows no fear in the brightness of his heart, or a man’s city, both are one, that still reveres the rights? (Eumenides 529-535 Fagles)

Fear has its place, it can be good, it stands sentinel, the watchman of the mind. It can be beneficial to suffer into sanity. How can the man or city that has no fear to nourish the heart ever have respect for justice? (518-525 Meineck)

Violence is Impiety’s child, true to its roots, but the spirit’s great good health breeds all we love and all our prayers call down, prosperity and peace. (Eumenides 542-545 Fagles)

Outrage is impiety’s true child, only a healthy mind provides the good fortune so cherished, the passion of all men’s prayers. (534-537 Meineck)

So you shall purge the evil from your midst. The rest shall hear and be afraid, and a crime such as this shall never again be committed among you. Show no pity: life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot. (Deuteronomy 19:19-21)

The Furies employ a slippery slope argument and claim that without the deterrent and fear that comes from a credible threat of reciprocity, humanity would descend into chaos.

Catastrophe! Ancient mandates will be usurped should the corrupt pleas of the mother-killer prevail. His crime will unite all mankind in anarchy and lawlessness, down through the generations, children will be free to harm parents, the fatal lesions tearing true… Now no one may call on us when disaster rains down. Yet they will clamor to cry, ‘Justice, where are you! Sovereign Furies!’ The tormented father, the mother just wronged, they will bemoan and wail the collapse of the house of Justice. (490-515 Meineck)

All this begs the question: If revenge and retribution are so great why would we ever adopt another standard of justice? Is a departure from retribution really the first step down the road of impiety, crime, chaos, and social collapse? Is this what’s wrong in the world today? Is the death penalty the only form of true justice currently in operation? Is the only correct direction for criminal justice reform a return to an “eye for and eye” mandate?

Despite the logic, symmetry, and power of the idea of retribution there’s something repulsive about it. The description of The Furies in The Oresteia is far from flattering.

In the opening scene of Eumenides the prophetess of Apollo describes a vision of what awaits her inside the temple that day, “But there in a ring around the man (Orestes), an amazing company- women, sleeping, nestling against the benches… women? No, Gorgons I’d call them; but then with Gorgons you’d see the grim inhuman…. But black they are, and so repulsive. Their heavy, rasping breathing makes me cringe. And their eyes ooze a discharge, sickening” (48-57 Fagles)

Shortly thereafter Apollo makes plain his feelings about them, “They disgust me. These grey, ancient children never touched by god, man, or beast – the eternal virgins. Born for destruction only, the dark pit, they range the bowels of Earth, the world of death, loathed by men and the gods who hold Olympus” (Eumedides 71-76 Fagles)

We also know that violent reprisals for violent acts has been the modus operandi of The House of Atreus for generations, and look at where it has got them. When Agamemnon enters the palace before his murder, Cassandra, his new young consort is left outside with the chorus of elderly Argives, and she erupts in fright as a vision of the horrors of the past and future unfolds before her. She sees the history of The House of Atreus and the adornment of the palace itself bears witness to the violence, “These roofs – look up – there is a dancing troupe that never leaves. And they have their harmony but it is harsh, their words are harsh, they drink beyond limit. Flushed on the blood of men their spirit grows and none can turn away their revel breeding in veins – The Furies! They cling to the house for life. They sing, sing of the frenzy that began it all, strain rising on strain, showering curses on the man who tramples on his brother’s bed.” (Agamemnon 1189-1198 Fagles)

The most powerful witness to the true nature of the human response induced by The Furies is the sudden change in Orestes following his acts of vengeance.

Orestes: I do not know how it will end. I am a charioteer with a runaway team, hurtling off the course, losing grip of the reins, losing grip of my mind, spinning out of control. My heart dances in terror and howls a furious tune… I must run from the blood that I shed, run from my own blood, no hearth will shelter me, only Delphi, it is Apollo’s will. I charge the men of Argos with remembrance: tell Menelaus the evil things that happened here. And now I go, an exile, banished from this land. In life as in death, my name will always be known for this.

Chorus: But you have done well. Don’t damn yourself with evil words, don’t let your tongue denounce you. You have liberated the entire city of Argos by beheading two snakes with one good clean stroke.

Orestes: Ah! Ah! Women, there! Like Gorgons! Black clad, writhing with snakes! I can’t stay here! I have to go!

Chorus: What is it? What sights swirl you into such a frenzy? You are the son of Agamemnon, be still, don’t surrender to fear.

Orestes: Not sights! These terrors are real! The mother’s curse, the hellhounds of hate, they are here! (Libation Bearers, Meineck 1021-1062)

Have you ever been filled with rage and a desire for revenge and then felt terrible after achieving your goal? I know I have. The rage subsides, but you are not restored, and the act of vengeance has actually tainted you.

Cleary there’s something deeply unsettling and unattractive about retribution. How can an idea be so satisfying and terrifying at the same time? How could it be so powerful as to have divine sanction and a departure from it deemed catastrophe, yet be described in such horrific and vile terms?

I think there is an insight in the plays. Most mortals do not see The Furies. The elderly Argives don’t understand Cassandra’s dread. Her behavior is chalked up to her change in station from Trojan princess to Greek slave. The Chorus in Libation Bearers constantly encouraged Orestes and Elektra in their revenge, and when complete, after The Furies descend on Orestes, the chorus is blind to their presence, it is he who bears the emotional weight of the act. Retribution as an abstract construct is attractive, in practice retaliating against violent acts with uncompromising violence results in deep physical and psychological harms. Note the differences in demeanor between those who call for war, and the wounded warriors who return from service.

After Apollo purifies and absolves Orestes, The Furies lash out at him and he bears witness to the effects of their demands, “Heave in torment, black froth erupting from your lungs, vomit the clots of all the murders you have drained. But never touch my halls, you have no right. Go where heads are severed, eyes are gouged out, where Justice and bloody slaughter are the same… castrations, wasted seed, young men’s glories butchered, extremities maimed, and huge stones at the chest, and the victims wail for pity” (Eumenides 180-187 Fagles)

We often personify justice as a blindfolded figure bearing a sword and balancing scales. Traditionally the blindfold signifies impartiality. Alternatively Gandhi offered the insight, “Eye for an eye makes the whole world blind”.

The text of Libation Bearers and Eumenides is clear that Orestes enjoyed divine sanction in his revenge, yet this did not prevent him from incurring the psychological scars of having murdered his own mother.

One might argue that all you have to do to avoid the wrath of retribution is not harm others and you’ll be spared this torment, but this isn’t true. Victims or those who care for them are forced into the business of retaliation. If I recall correctly the descent of the once upright protagonist into darkness due to the demands for revenge is the plot of several popular stories. The Godfather being the most obvious. Additionally the argument that punishment is avoidable supposes a human is capable of acting in complete accordance with established moral codes, and in my last journal I argued moral betrayal is inevitable, therefore I find this admonition unrealistic; everyone will both be in the business of dispensing and incurring reprisals. The whole world blind.

The problem is more profound when one examines the other side of the coin. What about those who do good? Why are they not spared from the negative consequences of the choices of others? Why are they not equally and proportionately recompensed for the good they do? I published something like 25,000 words on this conundrum in my series on The Book of Job, so I won’t retread that territory here. The short version is that a belief in the simplicity of the karmic balance of retributive justice can harm the innocent as well, and in the end Job arrived at a very different understanding about the relationship between moral behavior and justice.

It turns out that despite its appeal to whatever lurks deep in our hearts and minds, despite the satisfyingly simple intellectual framework, despite the dire warnings of those who favor it as a carrot/stick for human behavior, and despite the proclamations of divine sanction for retributive justice, humans have seriously discounted the idea. I’m sure there are a wide variety of reasons underpinning the migration to other formulations of law and justice, but there are very few examples of retribution in codified law.

I had a couple of reasons for quoting Genesis and The Law of Moses earlier. Not only to demonstrate the cross-cultural nature of the concepts, but also to underline the fact that the tension between retribution and alternative formulations of justice cuts across time and culture. Famously, Jesus of Nazzareth said “You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you: Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also, and if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, give your coat as well, and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the second mile. Give to the one who asks of you, and do not refuse anyone who wants to borrow from you. You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you: Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.” (Matthew 5:43-45)

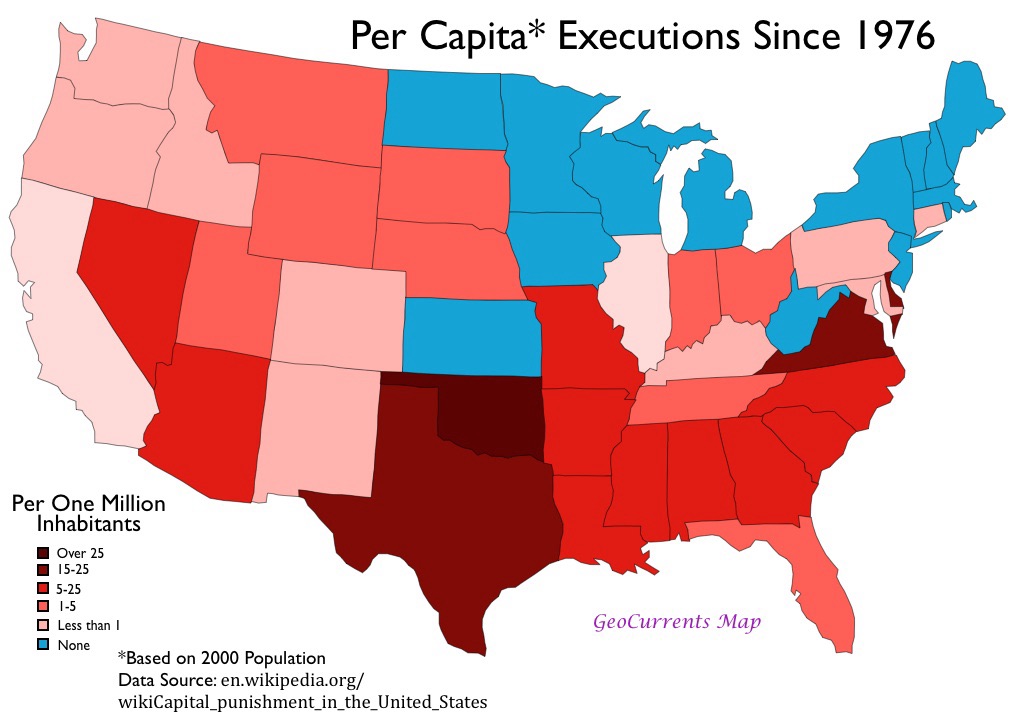

The standard set by The Sermon on The Mount is inspiring. If we use church attendance as a proxy for devotion to religious teaching, the overlap between those who are nominally Christian and attend church regularly and states that enforce the death penalty is noteworthy and underlines the struggle between our impulses for vengeance and the angels of our better natures.

The correlation may not actually be statistically significant, but I find it difficult to ignore.

The point isn’t to draw attention to this specific religio/political discrepancy, but to underline the contemporary nature of the philosophical divide Aeschylus examines. What system of justice could displace something as simple and powerful as retribution? What could entice a group to court the chaos promised by betraying karmic balance?

According to my music streaming service one of the songs I listened to the most in 2024 was Up The Wolves by The Mountain Goats. It’s a song about those moments when we know that forgiveness and mercy are what’s best for us, but we just can’t seem to let go of the desire for revenge. John Darnielle is famous for his delivery of moments of catharsis in his songs, and this one is no different. There’s a part of me that is ashamed to admit it, but I really love this song. Like the human situation it describes it is simultaneously beautiful and ugly.

All this to ask: Have we collectively suffered enough from retribution that we have learned a better way? Will we know the future when it comes?