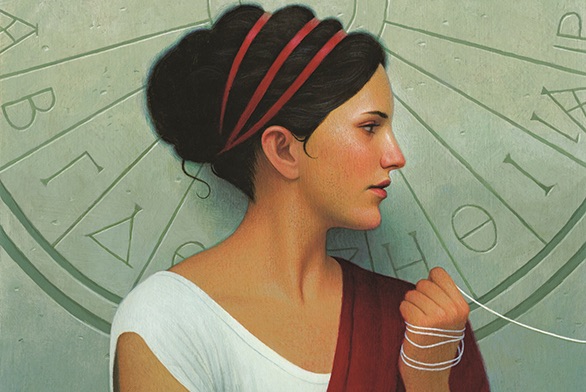

“What did she know?” and “when did she know it?” These two questions nag at anyone who considers Penelope and her role in The Odyssey. Penelope: long-suffering wife of Odysseus and mother of Telemachus, object of desire to over 100 young men, disenfranchised Bronze Age woman hobbled by culture in rectifying the chaos that envelopes her life and family. Penelope: single mother who raised a son capable of standing at his father’s side upon his return from war, woman of enterprise who maintained a thriving estate that could, for over four years, support over 100 unwelcome visitors sporting the appetites customary to young men, clever femme fatale who just so happened to host a contest that put a weapon only her husband could use into his hands so he could slaughter a room full of unarmed rivals. Which version of Penelope is more accurate?

The first word of The Iliad is “menin”, rage, the emotion that best describes Achilles and dictates the unfolding events of that story. In the opening line of The Odyssey Homer invokes the muses to tell the tale of Odysseus and the characteristic description used in describing the protagonist is “polytropos”, literally translated as “many travels” or “many turnings” but translators of The Odyssey have offered a variety of images to their readers. Robert Fagles chose “man of many twists and turns”, Emily Wilson went with “complicated”, Robert Fitzgerald, “skilled in all ways of contending”. After a bit of consideration I like the term enigmatic. Maybe that’s due to the images from the recent film The Immitation Game. No matter how you translate it, Odysseus’ travels, exploits, and the variety of problems he addresses fit the bill. His plans occasionally go awry, but in the end, if Odysseus and Homer are to be believed, he got the better of nearly everyone he encountered in his journeys home. Odysseus spent a decade at war in the name of another man’s wife. He spent years in the company of other women, Calypso wanted to grant him immortality, yet he passed on this offer to return to Ithaca. What sort of woman would inspire that sort of yearning from this sort of man?

Women are nearly absent from The Iliad, and as best I can recall The Odyssey fails the Bechdel test as well, but women are central to the plot and their agency is key to Odysseus’ success or failure. Athena initiates his homecoming by entreating Zeus while Poseidon is out of pocket in Ethiopia. Her ongoing active engagement is present at every pivotal moment of the story. Circe first entraps, then welcomes, and eventually guides Odysseus and his men on their journey. She helps them navigate to the Land of The Dead, chart the passage between Scylla and Charybdis, successfully bypass The Sirens, and she forewarns Odysseus against partaking of the Cattle of The Sun God. Calypso saves and nurtures Odysseus to health and offers him eternity on her island paradise, and ultimately relinquishes her hold over him and grants him freedom. Nausicaa also welcomes him to her island and cleverly arranges for his successful reception at the court of her parents. Finally, Penelope is not only faithful through twenty years of separation and welcomes her husband in disguise, but her actions facilitate the resolution Odysseus seeks, and she famously catches her clever husband off-guard when offering one last test of his identity. These women matter. It’s one of the arguments in favor of the idea that The Iliad and Odyssey were composed by different people.

Odysseus leaves behind a wise and worldly goddess when he departs Circe on Aeaea. He sails away from a goddess and her promise of immortality on an island paradise that impresses even Hermes when he leaves Calypso, and thankfully he passes on the opportunity to start over with a spiritely young girl possessing a quick wit when he declines to marry Nausicaa. A 50+ year-old man entering into a polygamous relationship with a teen bride may have been a bridge too far for Homer. His mind remains fixed on Penelope even after encountering Agamemnon in the Land of The Dead and being warned about the potential treachery awaiting him at home. Despite all the enchanting women he encounters, Odysseus is beguiled by only one.

The available evidence suggests that Odysseus values loyalty, courage, and a clever mind above youth, wealth, knowledge, comfort, and life itself, and in the end Penelope is the only woman for him.

The thing is when you read The Odyssey it’s clear that Penelope’s physical and emotional fidelity to Odysseus are never in doubt, but up until she gets the better of him regarding the nature and location of their marital bed, her intelligence and motivations for her speech and actions aren’t obvious. Is she the frustrated, but ultimately helpless damsel in distress whose actions only enable Odysseus because of his quick wits? Or is she the only one who recognizes her husband through his actions and words rather than through divine or direct revelation and cleverly plots alongside him the circumstances for his revenge?

What does she know? When does she know it?

I suspect an ancient bard’s performance: tonal changes, vocal inflections, and actions could have made it clear to an audience what he thought was going on in this relationship. The discrepancy between in person and other communication media we all experience informs us of the limitations of having only the written word. I’ll say up front I believe Homer’s text could be reasonably interpreted either way, but I find the strands of evidence that have been marshaled in favor of “she definitely knew at least as early as their conversation in the great hall” to be interesting and entertaining, so I’ll try to make the case here that Penelope commands Odysseus’ devotion precisely because she is clever and capable and they both enjoy that aspect of their relationship and employ it with devastating efficacy.

However, before we focus directly on Penelope I think a more detailed examination of Odysseus’ interaction with Nausicaa is worth our time and attention.

We first meet Nausicaa the morning after Odysseus, exhausted and nearly dead, washes up on the shores of Sheria after a vengeful Poseidon returns to the Mediterranean and realizes Athena is attempting an end-run to get Odysseus home while he was away. An enormous storm was conjured that destroyed his raft and after narrowly escaping being dashed against the rocks, he makes his way to the beach and buries himself in a pile of leaves under a bush. Nausicaa awakens from sleep inspired by a dream. She’s a teenager which means she is eligible for marriage. Her parents are king and queen of their prosperous, peaceful island kingdom, so the question isn’t if, but when and to whom and for what strategic purpose. Athena comes to her in the form of her bestie Dymas and chastises her for sleeping in. Everyone knows all the girls who please parents and society in general are anxiously engaged in hard work like doing the laundry, and if she wants a great husband soon she should get with the program and wash everyone’s clothes. There’s an implication that in doing so she will bring about her impending nuptials. Creepy and sexist? Absolutely. In tune with historic cultural norms of the time? Also, yes. Does it conveniently advance the plot? Definitely.

So Nausicaa tells her father she thinks it would be just splendid if she and some of her friends could take the wagon down to the seashore to do the laundry. After the clothing has been washed and set out to dry, she and her pals play some ball. It is to these shouts of glee and this day in the sun to which an exhausted and naked Odysseus awakens. As the wild man with the olive branch strategically placed in front of his body emerges from the shrubbery, most of the girls scatter but Nausicaa stays and engages the stranger. There’s a bit of repartee and both parties demonstrate their commitment to the norms of Xenia. Odysseus is tossed some soap and clean clothes. He retreats to the river and comes out a changed man, “as when Athena and Hephaestus teach and knowledgeable craftsman every art, and he puts gold on silver, making objects more beautiful- just so Athena poured attractiveness across his head and shoulder… his handsomeness was dazzling” (Wilson 6:232-238). This tall dark stranger has clearly caught the eye of young Nausicaa, and she thinks through the potential implications of rolling into town in the company of this man:

“The people in the town are proud; I worry that they may speak against me. Someone rude may say, ‘Who is that big strong man with her? Where did she find that stranger? Will he be her husband? She has got him from a ship, a foreigner, since no one lives near here, or else a god, the answer to her prayers, descended from the sky to hold her tight. Better if she has found herself a man from elsewhere, since she scorns the people here, although she has so many noble suitors.’ So they will shame me. I myself would blame a girl who got too intimate with men before her marriage, and who went against her loving parents’ rules”.

She decides it would be better if they show up separately. They divide the party as they approach the city gates. The plan works and Odysseus is welcomed to Phaeacia by King Alcinous and Queen Arete. Given the set-up of a girl dreaming about her impending marriage who meets a handsome stranger who quickly gains the good graces of her parents, it comes as no surprise the king quickly lands on the idea of offering Odysseus his own daughter’s hand in marriage:

“Athena, Zeus, Apollo, what a congenial man you are! I wish you would stay here, and marry my own daughter, and be my son. I would give you a home and wealth if you would like to stay.”

The glow-up Athena gave him must have really been something. That, or the lives of women and girls were so poorly valued that daughters could conceivably be given to newly arrived strangers whose identity hasn’t even been positively established. Odysseus politely declines and Alcinous agrees to send him back home after he’s been properly welcomed, rested, and laden with gifts. It’s during his stay among the Phaeacians that Odysseus unfurls his tales about the Cyclops, the Lystragonians, Circe, the Land of the Dead, the Sirens, the twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis, the Cattle of The Sun God, and his long stay with Calypso.

This stop among the Phaeacians conveniently sets up what is the most well remembered portion of The Odyssey and is the last stop before Odysseus finally arrives back on the shores of Ithaca, so a reader could be forgiven for glossing over this interaction with Nausicaa as nothing more than a plot device. Recently I heard an interview with Olga Levaniouk on the Ancient Greece Declassified Podcast which opened my eyes to what in retrospect is a painfully obvious bit of parallelism/ foreshadowing Homer plants here. Incidentally Lantern Jack’s podcast is a fantastic resource for a lay person to get excited about ancient history, literature, and philosophy. Let’s take stock of what has happened here. A young woman who is eligible to be married welcomes a stranger to her home and must navigate the social and potentially life altering judgments of her family and suitors, she is inspired by a dream, and develops a plan which enables Odysseus to safely and successfully gain the favor of the queen and return home.

Odysseus returns to Ithaca and reunites with a few loyal slaves and his son. He spends days gathering information about the exact situation he faces, judging loyalty of those in his house, and determining the best way to address the threats to his family. He enters his palace in disguise and endures verbal and physical abuse, but eventually everyone calls it a night and he is left alone in the main hall. In the quiet hours of the night Penelope enters in the company of several slaves, including an elderly slave, Euryclea, who has served as a nurse to both her husband and her son. Penelope has Odysseus brought before her and the two engage in the conversation which prompts the questions with which I began this essay: “What does Penelope know?” and “When does she know it?”. I’ll resist the temptation to go through it blow by blow, and I’ll try to stick to the highlights.

The first thing Penelope does is pry into the identity of her visitor, “I want to ask what people you have come from. Who are your parents? Where is your home town?”. Pretty straight forward. On the face of it, this might suggest she either doesn’t know or suspect it’s her husband who kneels before her. On the other hand she opens the door for him to communicate his identity to her.

His response is interesting, “This is your house. You have the right to question me, but do not ask about my family or native land. The memory will fill my heart with pain. I am a man of sorrow. I should not sit in someone else’s house lamenting”. Why not repeat the lie he’s told several times in the past few days? Does he not wish to lie directly to his wife? So the question of a positive ID of Odysseus by Penelope remains in doubt at this moment, but I think the information offered by Penelope with her next lines is interesting.

“Penelope said cautiously, ‘Well, stranger, the deathless gods destroyed my strength and beauty the day the Greeks went marching off to Troy, and my Odysseus went off with them. If he came back and cared for me again, I would regain my beauty and my status. But now I suffer dreadfully; some god has ruined me. The lords of all the islands, Same, Dulichium, and Zacynthus, and those who live in Ithaca, are courting me—though I do not want them to!—and spoiling my house. I cannot deal with suppliants, strangers and homeless men who want a job. I miss Odysseus; my heart is melting. The suitors want to push me into marriage, but I spin schemes… I have no more ideas, and I cannot fend off a marriage anymore. My parents are pressing me to marry, and my son knows that these men are wasting all his wealth and he is sick of it. He has become quite capable of caring for a house that Zeus has glorified.”

She offers up a compact history of the past 20 years, and lays bare her fidelity to Odysseus, her frank assessment of the crises coming to head, and her inability to forestall disaster any further. Why would she share this sort of information with a beggar? Does she suspect she’s speaking with her husband and is she communicating the urgency and anxiety she feels? Penelope demands to know the stranger’s identity and any news he has of Odysseus a second time. To be clear this “stranger” has been told that Penelope is kind and generous to anyone who claims to have any news of Odysseus and he has in fact claimed to have knowledge of Odysseus’ location and imminent return home. This claim is part of why the suitors and disloyal slaves have abused him so much. After the second demand, Odysseus gives Penelope a different lie than the one’s he’s given elsewhere on Ithaca, and may tip his hand when, after twenty years, he can describe Odysseus with detail and clarity right down to a brooch he was wearing when he claims he and Odysseus crossed paths on Crete all those years ago. This was a calculated response and it elicits the desired effect.

“These words increased her grief. She knew the signs that he had planted as evidence, and sobbed; she wept profusely. Pausing, she said, “I pitied you before, but now you are a guest and honored friend. I gave those clothes to him that you describe”

How likely is it that someone would remember the exact outfit Odysseus wore 20 years ago? We’re told several times Odysseus cuts an impressive figure, but Homer also leads us to understand the Achaean forces were chock full of god-like heroes during the Trojan War, and twenty years is a pretty long time. The stranger has more recent intelligence of repeated success and loss and a sequence of decisions that don’t make sense to me, but may have rang true to Homer’s audience, but the bottom line Penelope is told “I swear this by Zeus, the highest, greatest god, and by the hearth where I am sheltering. This will come true as I have said. This very lunar month, between the waning and the waxing moon Odysseus will come.” Odysseus has put an upper bound of 27 days (maybe as low as 14 depending upon how you interpret that phrase) for his own arrival. You’d think Penelope, who just laid bare her desperation, would welcome such a confident statement after 20 years of waiting. Note the content and tone of her response:

“Well, stranger, I do hope that you are right. If so, I would reward you at once with such warm generosity that everyone you met would see your luck. In fact, it seems to me, Odysseus will not come home. No one will see you off with kind good-byes. There is no master here to welcome visitors as he once did and send them off with honor.”

This shift in tone is curious. Based upon the dialogue earlier in the poem we’re conditioned to believe many strangers have taken advantage of her generosity by spinning tales of Odysseus so her indifference to this claim feels incongruous and therefore noteworthy. What is says to me is that she is no fool, and probably never has been. She is a kind, intelligent woman who knows that in order to get the truth about her husband no stone should be left unturned, but she is also skeptical of the information she receives as there is a clear incentive for informants to lie to her. Another perspective offered by Olga Levaniouk is that she has positively identified her husband and is actively negotiating with him. He has offered to rid the house of unwanted guests sometime in the next 4 weeks. Right now the ratio is 108:2, so he may need more time to sort out a plan and recruit more confederates, and he’s thinking a few weeks should be enough. This isn’t good enough for Penelope. She knows who she married. She’s heard tales of his genius and exploits at Troy, and if this man really is Odysseus and is worthy of regaining his place on Ithaca and her hand in marriage, then he must do better. Something like Shania Twain’s “Any Man of Mine” or Sheryl Crow’s “Strong Enough”.

After this possible rejection of the lunar month timeframe, Penelope walks away and sends in Odysseus’ old nurse to wash him. This is the moment Euryclea recognizes her master by the scar on his leg and we learn the story of Odysseus’ name. Does Penelope strongly suspect this man is Odysseus and so she sends in a woman who is loyal and in the best position outside of herself to confirm his identity based upon the presence of this scar? Is she quietly watching this all play out?

Immediately after Euryclea steps away Penelope returns with a new question. She asks Odysseus to interpret a dream she’s had. In the dream twenty geese came to the house and were eating all of her grain, but then an eagle swooped down and killed all the geese. Interestingly the dream offered its own interpretation. The Eagle spoke to her and said the geese were suitors and it is her husband Odysseus who will return and put a cruel end to them. This is also really bizarre right? She asks this stranger to interpret a dream that has no need for interpretation. It’s weird unless this is a second round of negotiations. Odysseus responds “there is no way to wrest another meaning out of the dream; Odysseus himself said how he will fulfill it: it means ruin for all the suitors. No one can protect them from death.” He confirms his intent. Penelope counters that sometimes dreams don’t come true, after all this is Homer not a Disney production, and she says that she’s made up her mind, tomorrow she’s going to host a contest, she’ll agree to marry whoever can string her husband’s bow and shoot an arrow through twelve axe heads. She’s forcing the timeline up. It’s been twenty years and she’s done waiting. Not 28 days, not 14 days, the deadline is tomorrow.

Tellingly the stranger suddenly moves up his timeline for Odysseus’ return, “Scheming Odysseus said, ‘Honored wife of great Odysseus, do not postpone this contest. They will fumble with the bow and will not finish stringing it or shooting the arrow through, before Odysseus, the mastermind, arrives.’” Penelope has backed him into a corner, and he has agreed to her terms. Tomorrow is the day. We all know what happens next. Odysseus comes through as promised.

Do you find this line of interpretation convincing? There’s no explicit narration or dialogue that confirms this is accurate. We know ancient Greek women were treated as property, objects to be traded, and it is therefore not unreasonable to envision Penelope as passive, the damsel in distress incapable of addressing the crisis to which she is beholden. Being treated as passive property does not mean that these women enjoyed, resigned themselves, or accepted this fate, but a narrator could certainly behave as though they did. The Homer of The Iliad did. Helen and Andromache spoke but were not heard and their actions and aspirations had no discernible effect on the plot. The Odyssey, on the other hand, is full of women actively engaged in life exercising agency with consequences for themselves and the events of the narrative. While I don’t believe Homer of The Odyssey was a proto-feminist, characterizing Penelope as a passive victim would be incongruous with the other women we encounter in this epic.

If we choose to believe that she is oblivious to Odysseus’ identity or is simply resigned to her fate, then why does she suddenly exercise her agency and make the apparently rash decision to host the contest the next day? Why now after twenty years? Why immediately after the conversation with someone who can offer a detailed description of her husband which apparently confirms that he can honestly claim to have seen him and who offers a compelling story for his imminent return within less than a month?

I would suggest we can either believe that Penelope just sort of stumbles through this scene and through dumb luck and desperation hits upon a plan that just happens to put a weapon only her husband can use in his hands, or we can believe that a storytelling professional has constructed a scene in which yet another intelligent and capable woman assists Odysseus on his path home through active participation and planning.

Remember Nausicaa? The girl facing an impending marriage, inspired by a dream, who tells Odysseus exactly how to navigate the city, gain favor, and puts him in position to displace her suitors and return home? Do we think it more or less likely that Homer would tell the audience two parallel stories where a teenager is smart enough to actively anticipate and navigate this delicate situation, but Odysseus’ dream girl, the one he passes on eternity on a tropical island with a literal goddess to return to, doesn’t recognize him and only incidentally puts him in the position to successfully regain her hand in marriage? I find that difficult to believe and I enjoy the idea of Penelope seeing through the ruse and so I choose to read their conversation as a thinly veiled negotiation. I find this a far more entertaining proposition. I will admit the discussion between Penelope and Euryclea at the beginning of Book 23 seems to contradict this assessment, but I believe one could interpret Penelope’s apparent disbelief at Odysseus’ return as her anxiety about his ability to successfully complete the task she set before him. It’s one thing to return and take on 100 enemies, another to defeat them. That may be a stretch, but it’s what I’m going with. I just really hate the idea that Penelope has been totally oblivious to all of Odysseus’ machinations and her role in them, but then somehow baits him into the famous olive tree bed fiasco.

To be honest the end of The Odyssey is not nearly as satisfying as The Iliad. I don’t think it would do to end on Book 22 with the slaughter of the suitors and disloyal slaves. I also think Athena showing up to stop the angry mob violence (it predates the term, but is basically a textbook deus ex machina) at the end of Book 24 is unsatisfying. There’s very little in Book 24 that I do like. The idea of Odysseus needing to deal with the angry families of his unwelcome suitors has a certain logic. He’s just murdered 108 of the most eligible bachelors from Ithaca and the surrounding islands. Combined with losing 600 other capable men at war and sea, it seems reasonable this might raise the ire of the local citizenry. On the other hand, to rush through it in the way the text does is totally incongruous with everything else that precedes it. Also, we are to believe the same island population that stood by while these ill-mannered lost boys ravaged Odysseus’ house for four years is now going to rise up in defense of some code of common decency? I kinda think Homer addressed those concerns successfully way back in book 1 when the suitors actively resisted and mocked the wisdom of the local council. If we’re in the business of tying up loose ends, the ending as presented in Book 24 fails to close the loop on the prophet Tiresia’s claim that Odysseus will not have completed his journey until he takes an oar to a land where they do not know watercraft and plants it in the ground. It is mentioned, but there’s no room for it to happen in Book 24, so if one claims that we’re looking to tell a complete story and not just end with a “happily ever after” scene, then we’re fooling ourselves. The reunion with Laertes could have been a touching finale, but the business of Odysseus screwing with his father and then glibly saying in essence “jokes on you dad! I’m back!” doesn’t do it for me.

If we are to claim this is a story of nostalgia, the pain of returning home, the story of a man who despite all his pain and suffering and all his losses, returns to a capable and loyal son and heir, and a faithful companion able to contend with a wiley and clever trickster, the story of how the adoption of the customs and rituals of Xenia mark one as civilized, and their abuse marks one as a monster, the story of how when we inflict pain on others we also inflict pain on ourselves, then there’s a place to wrap up the story which may not be perfect, but which is beautifully set and pretty natural:

“And when the couple had enjoyed their lovemaking, they shared another pleasure—telling stories. She told him how she suffered as she watched the crowd of suitors ruining the house, killing so many herds of sheep and cattle and drinking so much wine, because of her. Odysseus told her how much he hurt so many other people, and in turn how much he had endured himself. She loved to listen, and she did not fall asleep until he told it all. First, how he slaughtered the Cicones, then traveled to the fields of Lotus-Eaters; what the Cyclops did, and how he paid him back for ruthlessly eating his men. Then how he reached Aeolus, who welcomed him and helped him; but it was not yet his fate to come back home; a storm snatched him and bore him off across the sea, howling frustration. Then, he said, he came to Laestrygonia, whose people wrecked his fleet and killed his men. And he described the cleverness of Circe, and his journey to Hades to consult Tiresias, and how he saw all his dead friends, and saw his mother, who had loved him as a baby; then how he heard the Sirens’ endless voices, and reached the Wandering Rocks and terrible Charybdis, and how he had been the first to get away from Scylla. And he told her of how his crew devoured the Sun God’s cattle; Zeus roared with smoke and thunder, lightning struck the ship, and all his loyal men were killed. But he survived, and drifted to Ogygia. He told her how Calypso trapped him there, inside her hollow cave, and wanted him to be her husband; she took care of him and promised she could set him free from death and time forever. But she never swayed his heart. He suffered terribly, for years, and then he reached Phaeacia, where the people looked up to him as if he were a god, and sent him in a ship back home again to his dear Ithaca, with gifts of bronze and gold and piles of clothes. His story ended; sweet sleep released his heart from all his cares.”

The rage of Achilles is finally soothed as we bury Hector, Breaker of Horses, and as a result two great heroes get well-deserved rest. Imagine a piece of metal. Bending it into a new shape requires energy and places stress on the material. Stresses and forces applied correctly can make it into a desired form. Something useful like a spring, or a sword, or a plow, but apply force repetitively or indiscriminately, too much twisting and turning, and it may become brittle and break. Odysseus may or may not have broken in the same way Billy Pilgrim did, his fantastic tales may have been “what really happened” on his voyage home, but finally returning home, reuniting with his wife and son, our hero, the man of many twists and turns, unwinds and finds rest in the arms of a woman who understands and appreciates the resulting form.

Continuing the metaphor we all have a vision for the form we want our lives to take. That vision is informed by social constructs and expectations like Xenia & Patriarchy. The choices we make alter it. Do we enter the cave? Do we open the bag of wind? What song do the sirens sing? The result can be altered by the choices of others. Cyclopes, goddesses, and unwanted suitors. Finding a companion who appreciates the vision you have for yourself, but loves the twisted and perhaps even broken work in progress that is you is powerful. If Homer and Odysseus are to be believed that sort of relationship is powerful enough that a man will to go to hell and back, pass on eternity in paradise, and take his chances in a room full of would-be assassins for a shot at it.