Unsurprisingly, Enkidu’s death deeply disturbs Gilgamesh. Anyone who has ever lost a close family member or friend knows the hole that is left in one’s life. There are the obvious facts of their physical absence and all that comes with it. The gestures of love and kindness that you’ve taken for granted. The idiosyncratic behaviors you’ve perhaps begrudgingly adjusted to over the years that turned out to be endearing personality traits. Then there are the moments that occur suddenly or subtly when the loved one’s absence is acutely felt. “Grandma would have loved this” and “mom would have thought that was hilarious” or “if only I would have demanded grandpa share that cookie recipe”. Humans know loss and grief are defining features of our existence, but how we experience them, and how they manifest in our lives is so variable that I’m certain there’s no way to fully anticipate an individual’s reactions, nor is there a panacea to soothe the raw emotions one may feel.

Like all other aspects of his life, Gilgamesh’s grief takes epic proportions. I’m sure someone more culturally knowledgeable than I may be able to make more sense of Enkidu’s funeral, but the volume of preparations and number and nature of the details in a manuscript fairly bereft of detail suggest the author wanted to make it clear that Gilgamesh tried his best to give his friend a worthy send off. Everyone in Uruk joins their king in mourning. In a departure from his recent flaunting of religious convention Gilgamesh makes a series of offerings to gods of the underworld including Ishtar, “May Ishtar, the great queen, accept this, may she welcome my friend and walk at his side”. We mortals are certainly fickle. One minute you’re insulting the goddess of your city and refusing to become her consort. You’re riding high with your pal, ripping apart The Bull of Heaven and laughing at the impotence of the gods’ tool of vengeance, and the next you’re asking her to befriend a lost loved one.

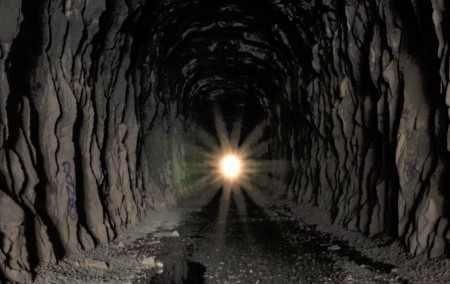

Once his friend has been laid to rest and public mourning has been observed Gilgamesh’s wanderings begin. He wanders the steppe, he crosses mountain passes, he battles wild beasts and wears their pelts in place of clothing, “Gilgamesh dug wells that never existed before, he drank the water, as he chased the winds. (George IX: 22). These wanderings take a toll on him and eventually he arrives at the abode of the Scorpion Men or Monsters, depending upon the translator, who guard the tunnel through which the sun passes every night as it journey’s back from where it sets in the west back to the east. The tunnel’s dimensions are such that the sun fills it completely so he must run the distance from east to west during daylight hours in order to make it out to avoid incineration by the sun when it enters the tunnel from the west. NBD. Gilgamesh, who fears but also demonstrates ambivalence about his own death, accepts the challenge and sprints through the profound darkness of the subterranean world for twelve hours and emerges just before sunset.

He then enters a beautiful “garden of the gods”, a wonderful place of fruit bearing trees and vines. This part is truncated due to damaged text, but we can feel certain he has found something special. The words that remain in the text are an assortment of precious stones and commodities; lapis lazuli, rubies, striped agate, crystal, turquoise, pearls, coral, and carnelian hang in bunches like grapes and lie on the ground like cucumbers and melons. I suspect this vignette serves two purposes. First, there’s the symbolic victory of a man searching to overcome death who leaves the light of day, enters the underworld at a sprint, and emerges on the other side into a beautiful garden of the immortal gods. Sounds like a win to me. Anyone familiar with the classic 1978 Richard Donner Superman Movie will recognize that the ability to run time backwards by manipulating the workings of the globe is genuine superhero stuff, and in a sense Gilgamesh has just pulled off a reversal of Genesis 3; he’s left the mortal realm of men and returned to a divine garden paradise. Obviously Genesis 3 is biblical, but I couldn’t help but conceive it in that way. It appears he meets a woman there, but the nature of this character, her words, and their interaction are lost to the ages. At least for now, who knows what might turn up? This is a bummer. The second outcome of traveling through the sun tunnel is that he has, by necessity, ended up at the western edge of the world. Many ancient cultures conceived of the west as the land of the dead specifically because it was where the sun died every night. The upshot to being on the edge of the world is that he is on the shore of a great expanse of water. For an ancient Mesopotamian audience: is this the eastern end of the Mediterranean? Does he make it all the way to the Atlantic Ocean? How would an audience who likely spend the majority of their lives on a vast plain imagine the edge of the world and the expanse of a sea or ocean? Having grown up along the Gulf Coast with easy access to the incomparable photography of National Geographic and PBS Nature I can’t conceive of what an amazing or incomprehensible scene this must have conjured.

To be honest, I don’t find the plot all that interesting from here on out, but I think there are a few aspects worth considering: His interaction with Siduri the tavern keeper, the journey across the waters of death, and the message that turns Gilgamesh away from his wanderings and leads him home. Despite the fact that he has wandered over desolate mountain passes and through a deep dark tunnel and landed on the far edge of the world, he isn’t alone. There’s a seaside inn. The text doesn’t give any clues as to whether this is a charming bed and breakfast type establishment or a seedy bar/ roach motel situation, but it is convenient. Siduri, the innkeeper, sees him coming, and notices that Gilgamesh cuts an impressive figure.

He was clad in a skin, he was frightful. He had flesh of gods in his body, sorrow was in his heart, His face was like a traveler’s from afar. (Foster)

She decides he is likely to be a dangerous, rough character and locks the doors to her tavern. Gilgamesh arrives and asks why anyone would close their doors to him. Is this a by-product of his noble position, or is he unaware of how disturbing his appearance is to others? At some point you’d think he’d get the hint. Every person, monster, god etc. he meets in his wanderings asks him why he looks so awful, and every time he gives essentially the same speech describing his woes:

Why should my cheeks not be emaciated, nor my face cast down, nor my spirit wretched, nor my features wasted? Why should there not be sorrow in my heart, Nor my face like a traveler’s from afar, nor my features weather by cold and sun, nor I be clad in a lion skin roaming the steppe? My friend, Enkidu, whom I so loved, who went with me through every hardship, the fate of mankind has overtaken him… I have grown afraid of dying, so I roam the steppe, my friend’s plight weighs heavy on me. How can I be silent? How can I hold my peace? My friend whom I loved, is turned to clay. Enkidu, my friend whom I loved, is turned to clay! Shall I too not lie down like him, and never get up forever and ever? (Foster)

At least he’s not in denial about the source of his mid-life crisis.

At this moment there are some lines that exist in an Old Babylonian text that do not appear in the Standard Version. Benjamin Foster and Stephen Mitchell include them, but Stephanie Dalley and Andrew George do not. George does note their existence and provides a translation of the text in a separate section of his edition. This is the moment I mentioned in my first essay where I said I’d be explicit about which source material of Gilgamesh I’d be using.

Siduri responds to Gilgamesh’s lament, it appears the trope of the wise bartender counseling a weary hero is as at least as old as the written word.

Gilgamesh, wherefore do you wander? The eternal life you are seeking you shall not find. When the gods created mankind. They established death for mankind, and withheld eternal life for themselves. As for you, Gilgamesh, let your stomach be full, always be happy, night and day. Make every day a delight, night and day play and dance. Your clothes should be clean, your head should be washed, you should bathe in water. Look proudly on the little one holding your hand, let you mate always be blissful in your loins, this, then, is the work of mankind, He who is alive should be happy. (Foster)

Gilgamesh is not impressed. All four versions I have re-align as he immediately asks her how to get to Utnapistim’s place. You can almost hear the sigh in her voice as she tells him about Ur-Shanabi and how to find him.

The interaction with Ur-Shanabi involves the fight in which Gilgamesh kills Ur-Shanabi’s crew. There’s the bit where Ur-Shanabi asks Gilgamesh why he looks so terrible and Gilgamesh repeats his lament. Then, Ur-Shanabi breaks the news that Gilgamash has rashly killed the crew whose special powers allow him to cross “the waters of death” and reach Utnapishtim’s island. Ultimately, he agrees to aid Gilgamesh and even figures out the means by which they’ll cross the sea. Gilgamesh must cut 300 poles, each one 100 feet long that they can use to push the boat across the waters. By using each pole only once they’ll minimize the risk of getting even a drop of the deadly waters on them. Perhaps Ur-Shanabi thought such an enormous feat of lumberjacking would dissuade Gilgamesh from his goal. If he thought that, he thought wrong. Ur-Shanabi must not have heard what happened to the Cedar forest of Humbaba. This is an interesting obstacle on the hero’s journey, but the thing I find interesting is how it frames Utnapishtim and his immortality.

We learn that Utnapishtim is from a city just upstream of Uruk, but now he and his wife live alone on an island off the far western edge of the world surrounded by the waters of death. Is this by necessity or by choice? Is there something about their immortality that demands this isolation? It turns out immortality and isolation were a package deal (XI: 223-230). I can’t help but once again think about the condition of Adam and Eve before partaking of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Alive, yes, but limited in their ability to enjoy it and live as we understand it. I love my wife, and I really enjoy spending time with her, but eternity with her and nobody else? That is except for the ferryman who shows up occasionally. No evenings out with friends. No trips to the theater to see a performance. Nobody to commiserate with when tragedy or boredom strike, or a domestic squabble erupts.. Nobody else with whom to talk politics or religion. Nobody to invite over to celebrate the spring, or the harvest, or the first snowfall. This isn’t exactly an attractive proposition when you consider it for any length of time, much less an eternity. I wonder how long it took for Utnapishtim to get all the household projects done before he ran out of things to do. This doesn’t even begin to contemplate the question of the meaninglessness of choice, value, and action when the denominator is infinity. Part of me can’t help but wonder if Enlil’s “gift” of immortality to Utnapishtim is actually his attempt to get the last laugh. Recall the circumstances of Utnapishtim’s grant of immortality: Enlil had just been confronted by the other gods and chastised for his actions in making the flood and wiping out the vast majority of humans. He was then directed to answer to those who survived when all others perished. At first glance eternity sounds nice, but I’ll take a hard pass on eternity in isolation. I’ll take a moment here to once again direct the reader to Steven Peck’s A Short Stay in Hell.

Perhaps their isolation would have been self-imposed even if they hadn’t been brought here by the gods? If you’ve achieved immortality and everyone knows it, then it’s only a matter of time before folks looking to do the same show up on your doorstep. Folks like Gilgamesh. There’s reason to believe these types of requests are unwelcome. After Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim, tells him his story, and asks how he too can achieve immortality; after Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh about the flood, and what rituals he used to please the gods, and explains that his circumstances cannot be repeated so Gilgamesh is SOL; after Gilgamesh asks to try anyway, when he fails and is sent on his way home; after all this, Utnapishtim tells Ur-Shanabi that because he brought Gilgamesh to him, he is not welcome back and should never return. I could see how telling that story over and over again, and knowing that people only ever want one thing from you would become tiresome. In that situation I might put some distance between me and my neighbors too. I might even put a deadly moat between us.

However, there’s part of me that wonders if there’s more to it. Myth often serves up cautionary tales about humans being granted gifts that are curses in disguise. King Midas being the most obvious example. Imagine the heartache of being immortal and seeing everyone you love grow old and die. Over and over and over again. Your children, and grandchildren. Your friends, and their children and grandchildren. Over and over and over again. I suspect that sort of pain is more likely to drive one into isolation than obnoxious neighbors. In a way Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality is a quest to forever re-live the pain of Enkidu’s loss. Understandably Utnapishtim and his wife felt fortunate in the moment they knelt before Enlil: there they were on a mountain, in the presence of the gods themselves, alive when so many others had perished, but how would they feel after a few millennia as they continue to live while everyone else around them dies? Over and over and over again. That’s some Twilight Zone / Dark Mirror type stuff. Did the Epic’s author see it this way? Did the poem’s audience? There is no explicit discussion reflecting this perspective, there’s only the oddity of their geography to suggest anything of the sort. In light of these considerations, perhaps it’s a good thing Gilgamesh is turned away after he gets a much needed nap.

Gilgamesh doesn’t gain immortality, and after leaving Utnapishtim he retrieves, but never partakes of the plant that would renew his youth. So what does he get for his troubles? Is he, and in turn all of humanity, left to despair the shortness and fragility of our lives and the pain of losing loved ones? Gilgamesh seems to remain in despair very late in the text. In line 335 of 353 of Tablet 11, after the snake eats the plant, Gilgamesh laments:

For Whom, Ur-Shanabi, have my arms been toiling? For whom has my heart’s blood been poured out? For myself I have obtained no benefit, I have done a good deed for a reptile!… How shall I find my bearings? (Foster)

The text doesn’t offer any explicit moral or conclusion. You’ll recall the closing stanzas of the epic are a repetition of the opening lines. In the opening lines the audience is encouraged to admire the walls and find the tablet containing the story, and the epic ends with Gilgamesh encouraging Ur-Shanabi to marvel at his city:

This is the wall of Uruk, which no city on Earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares. (Mitchell)

Is he admiring the human achievements of civilization? Community, construction, commerce, and cultivation? Is he supposed to admire the greatness of Gilgamesh as reflected by the magnificence of the city? Has Gilgamesh had a change of heart? Are these things genuinely inspiring to him, or is he attempting to put a positive spin on his return home as a consolation for the futility of his voyage? The ambiguity is one of the things that makes this text worth reading. The conclusions one reaches probably reflect one’s own perspective and values. Allow me to reflect on mine.

While I think the above conclusion is accurate, I also think the storytellers have embedded a few not so subtle hints at one perspective that could both honestly accept the failure of his attempt to gain immortality and also genuinely admire and embrace the beauty of human endeavor as an appropriate consolation. Recall what Siduri said to him at the inn:

Humans are born, they live, they die, but until the end comes, enjoy your life, spend it in happiness, not despair. Savor your food, make each of your days a delight, bathe and anoint yourself, wear bright clothes that are sparkling clean, and let music fill your house, love the child who holds you by the hand, and give your wife pleasure in your embrace. That is the best way for man to live. (Mitchell)

Of course that section comes from the Old Babylonian Version, and perhaps the Standard Version left it out on purpose. Maybe. Or maybe the standard version puts the same message in the mouth of another. After meeting Gilgamesh and hearing his tale of woe, the first thing out of Utnapishtim’s mouth is rebuke to Gilgamesh for wasting his life in the vain pursuit of immortality:

You hasten the end of your days. No one sees the face of death, No one hears the voice of death. There is a time for building a house, there is a time for starting a family, there is a time for brothers to divide an inheritance, there is a time for disputes to prevail in this world. There is a time the river, having risen and brought high water, mayflies are drifting downstream, their faces gazing at the sun, then, suddenly there is nothing! (Foster)

Sound familiar? I suspect it does. More on that momentarily. There’s one more example I want to relate. When Utnapishtim tells Ur-Shanabi he can never return to the island, he also instructs him to prepare Gilgamesh to return to civilization:

Take him, Ur-Shanabi, lead him to the washtub, have him wash his matted locks as clean as can be! ‘Let him cast off his pelts, and the sea bear them off, let his body be soaked till fair! Let a new kerchief be made for his head, let him wear royal robes, the dress fitting his dignity! ‘Until he goes home to his city, until he reaches the end of his road, let the robes show no mark, but stay fresh and new!’ (George)

I’ll point out here that these pieces of wisdom, while not identical, share a common thread to make the most of the good things in human life while we can. One should take advantage of the benefits of being a civilized human: construction, food, and clean body and clothing, and one should attend to one’s relationships: family, spouse, and in Gilgamesh’s case as the king of a city. In a way he is encouraged to live with the open embrace of the good things in life that Enkidu discovered with the aid of Shamhat, but also carry with him the circumspection both lacked prior to Enkidu’s death.

Now to the part where we examine the far more interesting Biblical parallel of the Epic of Gilgamesh I alluded to in the first essay, and which is hopefully very obvious at this point: Ecclesiastes. If the text of Ecclesiastes is to be believed its author, Kohelet, was a “Son of David”, which implies he was a King of Israel or Judah. By combining the historic reputation for his wisdom with his literal descendance from David have led some to conclude Solomon is the author or narrator of the text. Whatever the true identity of the author he famously opens up with the claim that he has essentially seen and done everything and that there is “nothing new under the sun” (1:9). In fact his lament is remarkably similar to Gilgamesh’s:

What do people gain from all the toil at which the toil under the sun? (1:3)

All is vanity and chasing after the wind (1:14, 17) (2:1)

Like Gilgamesh he has engaged in aggressive pursuit of pleasure and human accomplishment:

I will make a test of pleasure (2:1)

I made great works; I built houses and planted vineyards for myself; I made myself gardens and parks, and planted in them all kinds of fruit trees. (2:4)

I also had great possessions… and delights of the flesh, and many concubines (2:7-8)

Whatever my eyes desired I did not keep from them; I kept my heart from no pleasure (2:10)

Yet, the narrator concludes:

Then I considered all that my hands had done and the toil I had spent in doing it, and again, all was vanity and a chasing after wind (2:11)

Afterwards he sought for wisdom:

Then I saw that wisdom excels folly as light excels darkness. The wise have eyes in their head, but fools walk in darkness. Yet I perceived that the same fate befalls all of them. Then I said to myself, “What happens to the fool will happen to me also; why then have I been so very wise?” And I said to myself that this also is vanity. For there is no enduring remembrance of the wise or of fools, seeing that in the days to come all will have been long forgotten. How can the wise die just like fools? So I hated life, because what is done under the sun was grievous to me; for all is vanity and a chasing after wind. (2:13-17)

All of his experience leads the author to a place very similar to our hero Gilgamesh:

So I turned and gave my heart up to despair (2:20)

However, at this low point the preacher combines his understanding about the limits of human ability and the reality of human life and mortality and what comfort and goodness there is to be found despite all that confronts us:

There is nothing better for mortals than to eat and drink, and find enjoyment in their toil. (2:24)

Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.

Depending on your own background that statement may or may not provoke a measure of anxiety. Allow me to explain. When I was in high school I attended daily religion classes sponsored by the LDS (Mormon) church where we studied scripture, and LDS doctrine and theology. I woke up daily at 5:30 to do this and I attended faithfully for four years. Part of the curriculum at the time was a thing called “Scripture Mastery” which consisted of 100 specific verses of scripture, 25 each year drawn from The Old Testament, New Testament, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants and other canonized scripture of the LDS faith that constituted the focus of our study each school year. One of the Scripture Mastery selections for the Book of Mormon was 2 Nephi 28:7-9:

Yea, and there shall be many which shall say: Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die; and it shall be well with us. And there shall also be many which shall say: Eat, drink, and be merry; nevertheless, fear God—he will justify in committing a little sin; yea, lie a little, take the advantage of one because of his words, dig a pit for thy neighbor; there is no harm in this; and do all these things, for tomorrow we die; and if it so be that we are guilty, God will beat us with a few stripes, and at last we shall be saved in the kingdom of God. Yea, and there shall be many which shall teach after this manner, false and vain and foolish doctrines, and shall be puffed up in their hearts, and shall seek deep to hide their counsels from the Lord; and their works shall be in the dark.

There are substantial discrepancies between the ideas being contradicted in these verses and the conclusions taught by the author of Ecclesiastes; nonetheless for me, even in my estrangement from the religion of my youth, it feels a little disquieting to posit them as a viable, and admirable governing moral philosophy. It probably says more about my own disposition and understanding of what it means to eat, drink, and be merry than about LDS doctrine, but I’m not 100% certain a faith rooted in the reformist/restorationist movements of the 19th century American frontier founded by descendants of puritanical seekers doesn’t impose a certain sense of disapprobation on the idea that enjoyment of existence is the highest good. I will allow that one of the other Scripture Mastery verses from that same course of study concludes that “men are that they might have joy” (2Ne 2:25) so the idea of joyful existence is certainly present. The controversy lies in the definition of joy and how it is achieved. But I digress. The point is, that even though this idea is present in black and white in widely accepted Judeo-Christian scripture, I suspect I’m not the only person raised in the Abrahamic tradition who finds such a simple formulation of divinely appointed goodness to be not entirely coincidental with the remainder of the Biblical text and traditional beliefs.

If you’re unfamiliar with the text, this advice is not stated only once: it forms a refrain for all the wisdom dispensed by the author. Chapter 3 begins with the description of life popularized by The Byrds: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven” (3:1) which I’m sure Benjamin Foster intentionally mimicked when he translated Utnapishtim’s rebuke to Gilgamesh’s futile wanderings and abuse of his body. This list of aspects of life for which there is an appropriate time is followed by the conclusion:

I know that there is nothing better for them than to be happy and enjoy themselves as long as they live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all their toil. (3:12-13)

I won’t walk through the context of each one, but here’s list of all the places I highlighted where some version of “eat, drink, and be merry” is repeated in Ecclesiastes:

So I saw that there is nothing better than that all should enjoy their work, for that is their lot; who can bring them to see what will be after them? (3:22)

This is what I have seen to be good: it is fitting to eat and drink and find enjoyment in all the toil with which one toils under the sun the few days of the life God gives us; for this is our lot. (5:18)

So I commend enjoyment, for there is nothing better for people under the sun than to eat, and drink, and enjoy themselves, for this will go with them in their toil through the days of life that God gives them under the sun. (8:15)

Go, eat your bread with enjoyment, and drink your wine with a merry heart; for God has long ago approved what you do. Let your garments always be white; do not let oil be lacking on your head. Enjoy life with the wife whom you love, all the days of your vain life that are given you under the sun, because that is your portion in life and in your toil at which you toil under the sun. Whatever your hand finds to do, do with your might; for there is no work or thought or knowledge or wisdom in Sheol, to which you are going. (9:7-10)

Of course, you will recognize the last statement. This is the exact advice both Siduri and Utnapishtim give Gilgamesh when they tell him he has been chasing the wind in his vain search for immortality.

Is existentialism a meager consolation for those not granted immortality and eternal life by the gods, or is it a reasonable approach to develop a genuinely meaningful life in the face of the realities of human life? Some folks find the parallels between The Epic of Gilgamesh and the flood narrative to bolster their faith, but I’m drawn to the advice that the narrative suggests soothes the pain of loss and despair we may feel while navigating the vicissitudes of life. Enkidu’s wrath turned from Shamhat when he was reminded of the adventures and relationships he had enjoyed because of her intervention in his life. Gilgamesh transforms from a ruler who wore out his citizens, who selfishly stole from women and married couples, who wantonly destroyed a forest and abdicated his royal duties into a man capable of profound love for his friend, who admires the magnificence of those who make meaning through their relationships and work. Did Gilgamesh, and by extension the author and intended audience of the epic, actually embrace this perspective? The title character and the poem itself focus the reader’s attention upon the mighty works of humanity; the walls of Uruk. Are we to appreciate the expertise and hard work that went into building them? The lives they sheltered? Are we to marvel at the force of will and power of the ruler who directed their construction? Are we to admire the human ability to construct monuments that endure for what seems an eternity when compared to a single human life? Thousands of years later everyone had forgotten Gilgamesh’s name, and those walls had crumbled to ruin. It’s very much an Ozymandias situation. What survived the man and his works is the story about human frailty and the relationships that make it worthwhile.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is fiction, but I find its characterization of the exuberance and folly of youth, the bonds of friendship, and disorienting power of grief to be realistic. I’m on record as supporting the idea that meaning in human life is forged through our intent and actions, and I find the idea that actions guided by a desire to enjoy relationships with our friends and family and by work we find rewarding to be persuasive. It’s not shocking that’s the message I found in this story. Hopefully you’ve found some idea or connection in this most ancient piece of literature that you find worthy of consideration.

Climb Uruk’s wall and walk back and forth! Survey its foundations, examine the brickwork! Were its bricks not fired in an oven? Did the Seven Sages not lay its foundations? ‘A square mile is city, a square mile date-grove, a square mile is clay-pit, half a square mile the temple of Ishtar: three square miles and a half is Uruk’s expanse. (George)