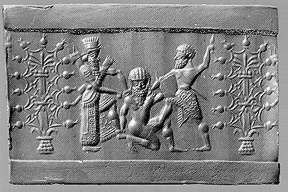

Enkidu’s narrative arc in the Epic of Gilgamesh isn’t particularly subtle. A man is crafted from clay. He roams the steppe with herds of wild animals. He wears no clothes, his hair is unkempt, he eats grass, he drinks water, he knows nothing of civilization. He is tamed through sexual intercourse which appears to sap some of his animal strength and energy that is replaced by “insight and understanding”. His story ends with his untimely death imposed by the gods themselves. It is very easy to hear echoes of Genesis 2 and 3 here and take this as a cautionary tale about the mortality and suffering brought to man by woman. Enkidu gives voice to this thought himself when he curses Shamhat on his deathbed.

Shamhat, I assign you an eternal fate, I curse you with the ultimate curse, may it seize you instantly, as it leaves my mouth.

Never may you have a home and family, never caress a child of your own, may your man prefer younger, prettier girls, may he beat you as a housewife beats a rug… may a tavern wall be your place of business, may you be dressed in torn robes and filthy underwear, may angry wives sue you, may thorns and briars make your feet bloody, may young men jeer and the rabble mock you as you walk the streets.

Shamhat, may all this be your reward for seducing me in the wilderness when I was strong and innocent and free. (Mitchell)

I don’t think this is a fair assessment of the situation, and neither does the sun god and patron of Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s adventures, Shamash. He points out Shamhat’s pivotal role in his life.

Enkidu, why are you cursing the priestess Shamhat? Wasn’t it she who gave you fine bread fit for a god and fine beer fit for a king, who clothed you in a glorious robe and gave you splendid Gilgamesh as your intimate friend? (Mitchell)

Ultimately, Enkidu does a 180 and offers her a blessing which is diametrically opposed to his original curse. Thus the storyteller entertains what one might consider a “traditional” interpretation of the role of women in the lives of men of clay, but rejects it. So what does his life and death mean? What are we to learn from his tale? I think the composer of the Epic had a pretty straight forward, clear-eyed view of the cause of Enkidu’s fall, and what it means. Bear with me while I take my usual meandering journey through the text.

Even before Enkidu hears about Gilgamesh inserting himself into the bridal chambers of newlyweds his natural confidence and strength predispose him to challenge Gilgamesh. As soon as he is rejected by his herd, and before he is properly civilized he learns of the existence of Gilgamesh and says

Come, Shamhat, escort me to the lustrous hallowed temple, abode of Anu and Ishtar, the place of Gilgamesh, who is perfect in strength, and so, like a wild bull, he lords it over the young men.

I myself will challenge him, I will speak out boldly, I will raise a cry in Uruk: I am the mighty one!

I am the one who will change destinies! (Foster)

What drives this intensity? This declaration is immediately preceded by the insight that “He was yearning for one to know his heart, a friend.”

Of course, we know that Gilgamesh also wanted a friend and had been having dreams that foretold the arrival of a companion. It may seem strange that a friendship would begin with a street brawl, but I can say with confidence many young male friendships begin with an element of rivalry and once the rival’s human qualities are assessed cooperation, trust, and friendship can frequently develop. This may be true of women as well, I couldn’t offer an opinion with any confidence.

There are several touching elements of their friendship beyond the business of conquering monsters. When they first bond, Gilgamesh’s mom makes it clear Enkidu is not the companion she expected for her great son, “Enkidu possesses no kith or kin. Shaggy hair hanging loose…he was born in the wild and has no brother.”

Enkidu overhears this assessment and is hurt and as tears well up in his eyes his new friend asks him what’s wrong. His response? “Cries of sorrow, my friend, have cramped my muscles, I am listless, my strength turned to weakness. Fear has made its way into my heart.” Enkidu comes off like a baby duck, once imprinted on a friend the thought of loss is devastating. This may seem extreme, but I remind myself of two things. The timeline isn’t clear. How much time elapses between the street brawl and Ninsun’s rejection? I doubt she was there in the moment, and mythological timelines are notoriously sketchy, so it’s reasonable to allow a bit more development through a musical montage of shared moments that makes this moment more relatable. Also, he has desperately wanted a friend since he first tasted the fruits of civilization, so the thought of losing one once he’s finally made a friend is understandably distressing.

When Gilgamesh hatches his idea of taking on Humbaba and bringing back lumber from the cedar forest, everyone tells him it’s a terrible idea. The elders of the city of Uruk, his new bestie Enkidu, even his mother tells him he’s crazy. However, once he’s brought on board, Enkidu is unwavering in his commitment to the expedition. In a touching moment of reconciliation Gilgamesh’s mother Ninsun adopts Enkidu and he swears oaths of loyalty to protect his friend on their journey and throughout their lives. They are brothers. Every night on the journey to the forest Enkidu makes Gilgamesh’s bed and keeps watch over him. Every morning Gilgamesh awakens suddenly, distressed by dreams he doesn’t understand. I believe the name for these types of dreams is nightmares. Enkidu offers confidence inspiring, and ultimately correct, interpretations for him. Once they finally arrive at the forest’s edge Gilgamesh hesitates, his bravado momentarily gone, “As the cedar cast its shadow, Gilgamesh was beset by fear. Stiffness seized his arms, then numbness befell his legs.” Enkidu, offers a brief pep talk before they enter. This process of Gilgamesh being suddenly seized by doubt, followed by a reinvigorating speech from Enkidu repeats numerous times in the forest as Humbaba taunts and threatens them.

Humbaba: You dare to lead Gilgamesh here, you both stand before me looking like a pair of frightened girls. I will slit your throats, I will cut off your heads, I will feed your stinking guts to the shrieking vultures and crows.

Gilgamesh backed away. He said, “How dreadful Humbaba’s face has become! It is changing into a thousand nightmare faces, more horrible than I can bear. I feel haunted. I am too afraid to go on.”

Enkidu answered, “Why, dear friend, do you speak like a coward? What you just said is unworthy of you. It grieves my heart. We must not hesitate or retreat. Two intimate friends cannot be defeated. Be courageous. Remember how strong you are. I will stand by you. Now let us attack.”

Gilgamesh felt his courage return. (Mitchell)

As is so often the case in hero stories, our heroes triumph over Humbaba. An interesting thing happens during the battle. We learn that Enkidu and Humbaba have some history. When he first sees Enkidu with Gilgamesh, Humbaba taunts him and reminds him that he could have killed Enkidu when he was younger. Exactly how one reconciles this detail with Enkidu’s chthonic origin is not clear, but it doesn’t seem to intimidate Enkidu. Gilgamesh invokes the aid of his patron deity Shamash who provides the gale force of “the thirteen winds” and Humbaba is defeated. As the battle progresses Humbaba switches from taunting and threatening to begging for mercy, and finally cursing our heroes, specifically cursing Enkidu who, as a man born in the wild, should be on the side of the natural world rather than accompanying the ruler of human civilization in his quest for domination.

He pleads with his adversaries and their god:

He [Humbaba] lifted his head, weeping before Shamash, his tears flowing under the rays of the sun: ‘When Enkidu lay asleep with his animals, I did not call out to him; mounts Sirion and Lebanon, growers of cedar, had never been spoilt. ‘As you, O Shamash, are my lord and my judge, I knew no mother who bore me, I knew no father who reared me, it was a mountain that bore me and you that reared me! ‘O Enkidu, my release rests with you: tell Gilgamesh to spare me my life!’ (George)

When the chips are down he closes with this curse:

May the pair of them not grow old, besides Gilgamesh his friend, none shall bury Enkidu! (George)

Here we get the first foreshadowing of Enkidu’s fate. Shamhat may have seduced him and brought him to civilization, but it’s Enkidu’s choices that lead to his downfall. He refuses to show Humbaba mercy even though the guardian of the forest appealed to their shared wild origins, their common god, and offered to allow them to take as much lumber as they wanted. He chooses to support his friend and drives Gilgamesh forward with promises of fame and glory that accompany their heroic deeds and conquest of the natural world.

Finish him, slay him, do away with his power! ‘Before Enlil the foremost hears what we do, and the great gods take against us in anger, Enlil in Nippur, Shamash in Larsa …, establish forever a fame that endures, how Gilgamesh slew ferocious Humbaba! (George)

After slaying Humbaba, Gilgamesh sets out on phase three of the “Journey to the forest, slay the monster, collect the materials for an ambitious construction project, and return home a hero” four part plan. They are going to need a lot of wood to complete the doors and gates he wants to build and the special axes they brought are up to the job. Swung by men as large and powerful as our heroes, 5 foot (3.5 cubit) splinters fly out of the tree trunks as they fell the mighty cedars. As they work Enkidu looks around and comments “My friend we have made wasteland of the forest, how shall we answer for it to Enlil in Nippur when he says: You slew the guardian as a deed of valor, but what was this, your fury, that you decimated the forest?” (Foster). He’s obviously aware that Humbaba’s curse may be more than the words of a desperate monster. Their actions transgress the natural and divine order of the world. He finds and chops down the tallest tree in the forest to construct an enormous door for Enlil’s temple in Nippur. Enlil is the god who sent the flood, he is a warrior god who also carries the title “the counselor” and from what I can tell he fills something akin to the role of satan “the accuser” in the book of Job. The god Enki is also known as a counselor, but is kind and also a god of fertility, craft, art, and creation. The two make a dyad of divine, eternal opposites. Where have we heard that before? Bottom line, staying on Enlil’s good side seems like a good idea, but Enkidu and the reader can’t help but feel a measure of foreboding in the wake of this triumph.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu return to Uruk aboard a raft constructed of felled timber. They float down the Euphrates bearing the head of the slain Humbaba. After they get home and get a bath and some clean clothes, Ishtar propositions Gilgamesh and his rejection of the goddess is the exact opposite of the gentle let down “it’s not you, it’s me”. In my last essay I offered an extensive quotation of the rejection; basically he says she’s fickle, and once a man bores her he meets an undesirable end. Multiple myths suggest rejecting the overtures of a goddess are a reasonable, if bold and fool-hearty, decision by Gilgamesh.

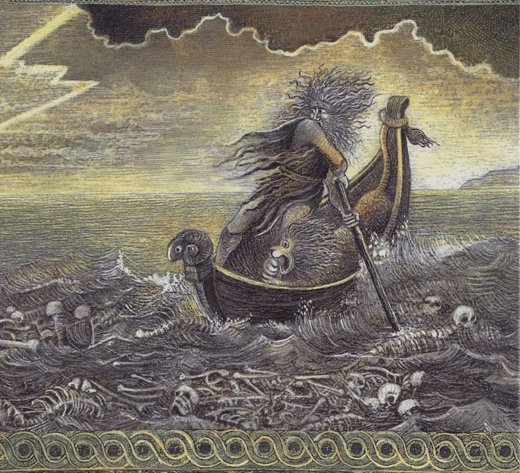

We don’t have enough stories to make sense of the entire list of Ishtar’s past doomed lovers in Gilgamesh’s rejection, but one carries a lot of weight. “For Dumuzi, your girlhood lover, you ordained year after year of weeping.” In Greek mythology Aphrodite, goddess of sexual passion and desire, drove humans and gods to all sorts of acts that spun out of control and ended badly. The Trojan war is the most obvious example, but there are far too many to count. With the notable exception of Zeus turning the tables and having Aphrodite fall for Anchises resulting in the birth of Aeneas, the Greco-Roman deity usually kept her distance from the types of trainwrecks she inspired in others. The Mesopotamian goddess of sexual passion, Ishtar or Inanna depending on geography and timing, appears to have been a bit more engaged in the business of seeking the fulfillment of her own desires. There are several extant tales of her tempestuous relationships and even an attempted coup against her sister, Ereshkigal, the ruler of the underworld. In truth she strikes me as an ambitious mashup of Athena, Aphrodite, and Demeter with aspirations of adding a dash of Persephone to the mix. Demuzi or Tammuz (again depending upon geography and timing we’re talking about cultural change and syncretism over more than a millennium here) was her consort and there are a few versions about how their relationship worked. Some versions have Demuzi being killed in order to ransom Ishtar from the underworld after she is captured by her sister following the failed coup. Demuzi’s own sister, Geshtinanna, volunteers to take his place for half the year (shades of Persephone in Hades) and so every year he is reborn, remarries Ishtar, lives until the agricultural cycle runs its course for the year, and is then killed like harvested grain or slaughtered livestock. This business of birth, growth, death, and renewal fits the character of a god of agriculture and pastoralism. In other versions the background of Ishtar and Erishkigal’s conflict is not the driving force of his death. In one version, Ishtar arranges for his murder because she is jealous that Demuzi is “initiating” the sexual lives of the young women of Uruk. Sound familiar?

While it’s unclear which version was current when and where the Epic of Gilgamesh was composed, we know something about how vital this myth of fertility, and the cycle of birth, growth, death, and rejuvenation was to the people of Mesopotamia. In the vicinity of, and at about the time Gilgamesh is believed to have ruled over Uruk there are records that describe annual celebrations where the king of the city, serving as proxy for Demuzi, would marry the priestess of the temple of Ishtar or Inanna, and that the consummation of this marriage would ensure fertility for crops and livestock for the year. Later, at harvest time, the king would be symbolically sacrificed and mourning processions were held for the slain god.

Hopefully the point of this digression is obvious. The events of The Epic of Gilgamesh extensively subvert this paradigm. It is Enkidu, not Gilgamesh the king, who engages sexually with a priestess of Ishtar. Additionally when formally propositioned by Ishtar, Gilgamesh rejects her. He’s not just rejecting a goddess of renown fickle affections, he is rejecting the ancient traditions, rites, and rituals which ensure fertility in the land. He’s abdicating his duty as king. I think this insight is lent credence by the conversation between Ishtar and her father Anu, when discussing how to avenge her insult, and in the effects of the arrival of The Bull of Heaven.

Anu opened his mouth to speak, saying to the Lady Ishtar: “If you want from me the Bull of Heaven, let the widow of Uruk gather seven years’ chaff, and the farmer of Uruk grow seven years’ hay.” (George)

There’s some lost text here so it’s not clear if 7 years of plenty pass between insult and injury and the release of the Bull of Heaven, or if there have already been 7 years of plenty (Joseph in Egypt anyone?) and the bull is released immediately, but ultimately Ishtar satisfies this demand.

Anu heard this speech of Ishtar, the Bull of Heaven’s nose-rope he placed in her hands. Down came Ishtar, leading it onward: when it reached the land of Uruk, it dried up the woods, the reed-beds and marshes, down it went to the river, lowered the level by seven full cubits. (George)

It seems the Bull of Heaven possesses fiery snorts and/or an intense thirst that runs rivers dry. In light of all the sacrilege that has already occurred, the business of Enkidu throwing the bull’s body parts around and hurling insults at Ishtar takes an even sharper edge.

I suspect this conflict takes on even greater import when we consider that the patron god of Gilgamesh is Shamash, who by some accounts is Ishtar’s brother, and is a sun/ sky god. Are we witnessing the displacement of an immediately present, female, earth/fertility goddess by a distant, male, sky god as a recurrent historical theme, as has been posited by some to account for the ubiquitous scattered prehistoric goddess statues? Are we in the midst of a shift from true polytheism to henotheism? Henotheism is the practice of giving primacy to one specific god within a pantheon which some scholars of religion believe serves as a transition towards monotheism.

The Enuma Elish is often described as “the creation story” of mesopotamia myth. It certainly fits that category in that it describes how the world we inhabit came into being, but when you actually read the poem, creation is only a small, secondary fragment of the story. I think it would be more appropriately called the Hymn of Marduk. The actual story arc is that of how Marduk, a 5th generation sun/sky god, became king of the gods by leading a coalition that overthrows and kills his great great grandparents. It gives the background of the conflict, describes the conquest and subsequent act of creation where the universe is created from the dead body of the mother goddess Tiamat. That all happens in the first 30% of the text. The remainder is all about how the other gods bow down to him, and it lists of the admirable attributes and glorious names of Marduk. Marduk is a Babylonian god, but his attributes are roughly similar to Shamash. In my mind the clearest evidence of their potential parallel roles is that Marduk defeated Tiamat and took control of the tablets of destiny through his use of The Thirteen Winds, the same weapon Shamash used to help Gilgamesh and Enkidu defeat Humbaba. I personally doubt all of this is a coincidence. Does the author of the epic support a move away from traditional views towards an elevation of Shamash over other gods? Does the narrative simply reflect the beliefs of its times without editorialization from the composer? Or are we reading a cautionary tale about the dangers of dispising the old ways? I think a reader could reasonably argue any of these points of view. The bottom line is that I think Enkidu’s and Gilgamesh’s repudiation of Ishtar carried significant cultural weight for the original audience.

Our heroes have defeated a frightening monsters, defended their city from disaster, completed great public works, and offered gifts to the gods, but they’ve also subjugated the natural world to their will, rejected traditional roles and theology, and defied the heavens, going so far as to insult and mock the goddess whose temple (Mesopotamian belief assumed their gods were literally, physically present in their idols and temples) was located in their city. Based on this, there is no mystery why the gods demand one of their lives.

Before we kill anyone off, let’s consider Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship. One of the great rhetorical triumphs of the epic is how Enkidu’s and Gilgamesh’s characteristics complement one another. They are not entirely parallel, but they are not opposites. They are both powerful, willful, charismatic men of action. Before he is civilized Enkidu is a thorn in the side of hunters and herdsmen, and Gilgamesh “wears out” the men and women of Uruk. Both are inspired by, and talk of winning glory and renown through their exploits. Whenever one is hurt or afraid, the other steps in to help and comfort. Enkidu has no family or history; he is molded of clay, while Gilgamesh is a prince born and raised to rule, yet both rise above typical mortal concern and experience to reach heroic heights. In the forest Enkidu repudiates his connection to the wild and encourages Gilgamesh to give Humbaba no quarter despite his pleas for mercy. He personally seeks and fells the tallest of the cedars. Gilgamesh appears to reject both the proxy role of Demuzi and the literal advances of the goddess Ishtar. These guys have found kindred spirits in one another, their relationship takes primacy over all else.

Most are aware the English word for love is often insufficient to capture the various forms of intimate relationships we experience. Inevitably these discussions find their way back to Greek words, Plato, Socrates, and The Symposium. I won’t go that far, but I think the familiar terms that issue from these discussions make useful distinctions. There’s Eros, erotic love: sexual passion. There’s Pragma, pragmatic: the type of practical, functional relationship that develops with time and experience. Storge, love of family, tribalism. Mania, obsessive love. Agape, unconditional love for all, famously the word employed in the Pauline epistles extolling the love of Christ and Christian charity. Finally, there’s Philia, brotherly love, a deep intimate friendship that is encouraging, kind, and affectionate, the Platonic ideal of love.

Enkidu’s relationship with Shamhat shows the power, pitfalls, and limits of Eros. Ninsun’s rejection and then adoption of Enkidu serve a similar role for Storge. The drive to defeat Humbaba and devastate nature to complete a human project is a recognizable example of Mania. I’m not sure there are great examples of Pragma or Agape in the first 7 books, we’ll have to keep our eyes open through the second half of the poem, but I think the most thorough examination of human love in the text is that of Philia. Enkidu and Gilgamesh are larger than life characters. Their adventures are properly described as epic in scope, but alongside a rollicking good time of this bromance buddy comedy the composer has developed a model of the platonic ideal of brotherly love. It’s a step by step manual of how to make a friend. Know your strengths, test them out in the world. Find someone who challenges what you think you know about yourself, but who respects you for those strengths. A friend is often willing to overlook some of your failings, but lifts you up when you fall down. Find someone whose companionship, esteem, and loyalty you value over social judgments, and in whom all these feelings and behaviors are mutual. Find you someone who looks at you the way Gilgamesh looks at Enkidu.

One last brief digression then I swear I’ll wrap this up. Anyone who made it through my series of The Iliad might have noticed I didn’t spend much time on the exact nature of Achilles’ and Patroclus’ relationship. Why exactly is Achilles so broken up over Patroclus’ death? He weeps over his body for days and dreams about him in the few moments sleep overtakes him. Did they have a homosexual relationship? People have speculated upon this for some time. The relative acceptability of homosexuality in classical Greece renders such speculation not unreasonable. Madeleine Miller explored this explicitly in her recent novel Song of Achilles. I’ll go on record as saying I honestly don’t care and that’s why I didn’t go into then. If conceiving their relationship as homosexual makes the story more real or identifiable for you, then great. There’s plenty to work with to support that view. If the thought makes you uncomfortable, maybe you should wrestle with why that is, but it’s fine and reasonable to read them as two great friends. I bring this up because it seems the same question can be raised here. Both men have pretty strong heterosexual credentials established in the text, but so does Achilles in The Iliad. Clearly, I have no problem reading what I want in these stories, and allow others the same privilege. The line of reasoning I’ve occasionally heard that makes me uncomfortable and sad is the idea that absent some measure of homosexuality two men could not have maintained a close relationship of compassion, respect, kindness, and affection. I know the sample size is small, but in two of the foundational epics of the ancient world we find two examples of such relationships. We’re batting 1,000 here. If you’d like a third or fourth from a non-pagan tradition, go ahead and check in on David and Jonathan, and Jesus and John. Still batting 1,000 with Abrahamic tradition putting a double into play. If our culture 3,000 to 5,000 years later cannot conceive of two charismatic, powerful, brave, kind men maintaining a loving friendship without homosexuality, then I think the problem may be that our concepts of masculinity and human relationships are seriously out of whack. I believe the preferred nomenclature for the dysfunctional views which would fit this description is “toxic masculinity”. Are Enkidu and Gilgamesh in a Brokeback Mountain situation? Maybe, but the idea that they MUST be would constitute an indictment of our own culture to understand Philia independent of Eros. /End rant

Well Mark, if you’re so smart, and this is a touching tale of intimate friendship, why does the author kill off one of the main characters as an act of divine justice? Great question. First, we must recall that the Mesopotamian pantheon was not conceived of as benevolent, so their will is not necessarily just, so divine vengeance would be a better characterization of Enkidu’s death. Second, who was it that said Enkidu needed to die? That’s right: Enlil, the accuser, the guy who sent the flood. Being killed by this crowd of deities at the encouragement of that specific god ain’t exactly equivalent to genuine moral condemnation. On the other hand, it’s clear that Enkidu and Gilgamesh have affronted both the gods and the natural order of things, and if you’re gonna hold society together with stories of gods and divinely appointed rulers, then telling stories of insulting the established order with impunity simply will not do. So, it’s not surprising that someone gets killed. That may be true, but why Enkidu and not Gilgamesh? I think the reason Enkidu is the one to die is because that’s his job. That’s what he was created to do. Recall why he was made. Gilgamesh was wearing out the citizens of Uruk and they cried to the gods to humble him. Enkidu’s death is how that end is accomplished. I discussed my distaste for a god that would purposely manipulate or use human life and suffering to serve their own ends in my first essay on The Book of Job. My opinion hasn’t changed. Gods who behave in such a manner are unworthy of worship and devotion, but I digress.

When Enkidu rolls into town and everyone marvels at his greatness and he rumbles in the streets with Gilgamesh we half expect Enkidu to win, because we know his origin and the purpose of creation. It is not unreasonable to assume that his divine creation and mandate endow him with physical abilities to overcome Gilgamesh and take him down a peg. But he doesn’t. Gilgamesh lifted him over his head and “knelt for the win”. The buddy comedy follows on the heels of the street brawl so swiftly the reader can be forgiven for forgetting Enkidu’s true purpose. Physical domination may seem like the obvious way of humbling a character like Gilgamesh who ”strides about like a wild bull”, but epic poetry often does not work that way. Achilles’ coup against Agamemnon fails, killing Hector brings him no comfort, he is dead before Troy falls. Physical acts move the plot, but the real action is psychological. Even 4000 years ago poets knew that the human mind and heart have depths that transcend physical strength and social constructs. Enkidu and Gilgamesh develop a great, intimate, loving friendship based on mutual respect, trust, and compassion, and when deprived of that relationship Gilgamesh is sent into a spiral of despair that will take him over the mountains, to the ends of the Earth, and even across the waters of death.

Enkidu is a companion created by the gods who brings sorrow to his recipient. Sound familiar? Shamhat may not have been the cause of Enkidu’s fall, but Enkidu’s presence and then loss is what up-ends Gilgamesh. Returning to parallels within Genesis: a more charitable interpretation of the action within the Garden of Eden is that Adam and Eve’s minds, hearts, and relationship blossomed and reached a point where their understanding of their existence and commitment to one another transcended their relationship to their creator. Adam knew the loneliness of life without companionship and knew an eternity alone was far worse than a short life filled with pleasure and pain because he had a genuine companion in Eve. Their time together helped them to know and distinguish between good and evil in their lives and once they had a handle on things they chose the uncertain adventure of life beyond the boundaries of the garden and their relationship over perfect order and stasis under the watchful control of the divine. The rumor is that the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil was delicious to the taste and very desirable. The idea that the pleasure of companionship and how to sustain it naturally entails the inevitable pain of loss checks out. The idea that grief and sorrow as the price for loving human companionship is somehow the vengeful will of the gods is troubling and liable to send me off on a rant, so I’ll let the reader consider or reject that thought without more of my biases. I’m not alone in this thought. I think it noteworthy that the conclusions Gilgamesh reaches in his search for understanding and comfort do not come from the gods. We’ll follow along with Gilgamesh and wrap this up next time.