On the evening of December 3, 1872 George Smith stood before the Society of Biblical Archeology inside The British Museum and read the text of his exciting new work: The Chaldean Account of The Deluge. His words echoed far beyond that meeting. The excitement raised that evening resulted in multiple expeditions to the Middle East and at least two books before his death in 1876, and many are excited by what he found to this day.

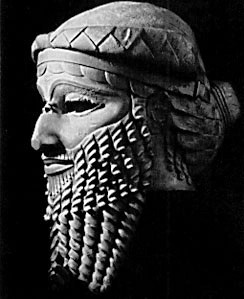

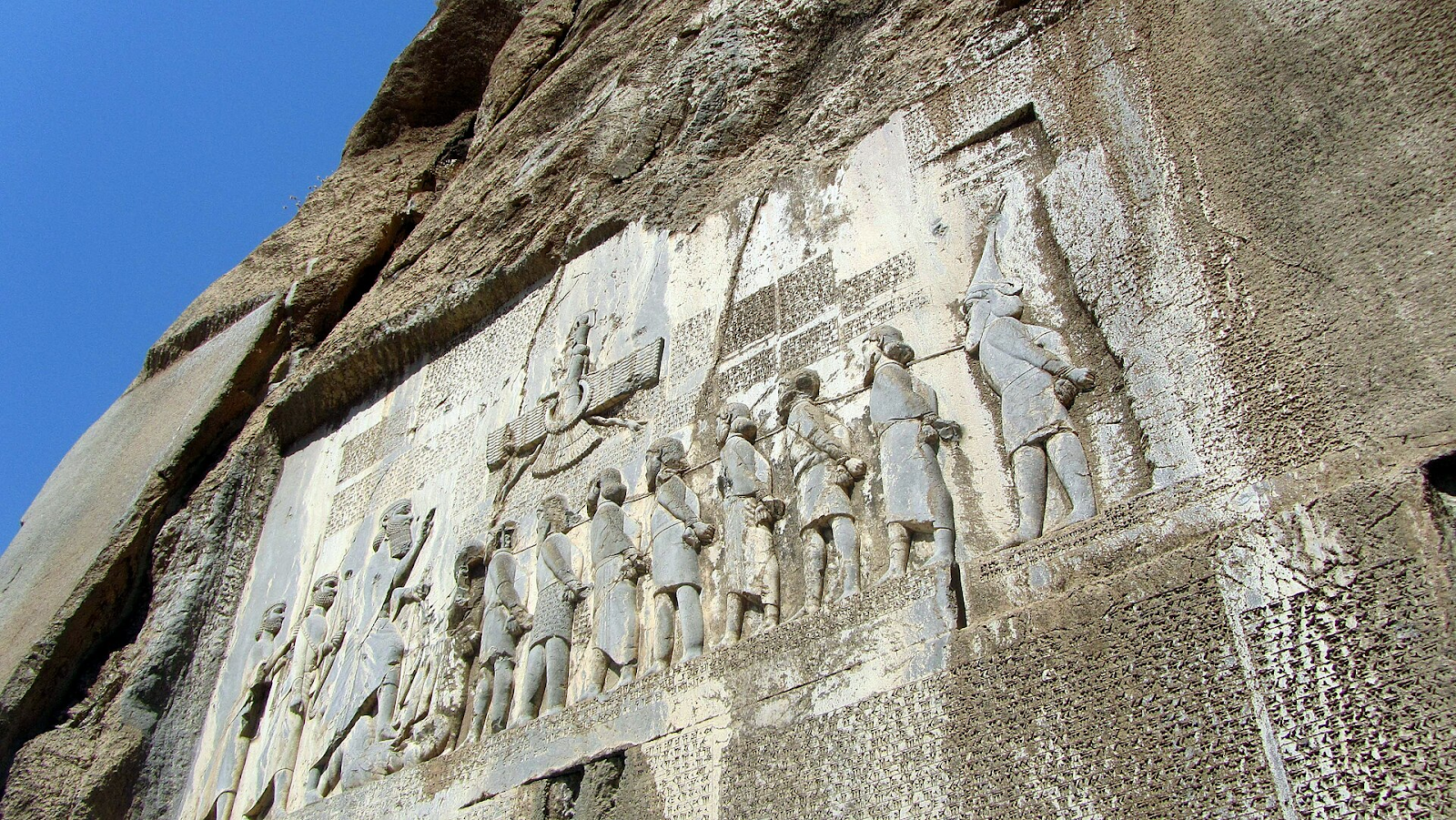

In the 1840s excavation of an incredible trove of clay tablets was begun at the ruins of Nineveh, one of the capitals of the Assyrian empire. Some folks recall that name as the proposed destination for reluctant missionary turned temporary involuntary marine biologist, Jonah. Nineveh was home to several Assyrian emperors including Sennacharib and Ashurbanipal. During its period of prominence in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, multiple libraries were promulgated in the imperial palace and various local temples. Over 20,000 clay tablets were excavated from various sites in the first 20 years of study. Initially the writing, known as Akkadian cuneiform, was indecipherable. But thanks to a few very smart people, a few educated guesses and something called the Behistun inscription, a 50’ X 80’ bas-relief carving 100’ up a limestone cliff extolling the greatness of the Persian emperor Darius I, the text of the tablets was translatable by the 1850s.

The main barrier at this point was that nobody knew where to start to find the cool stuff, most archeological records are administrative documents (death and taxes), and nobody had bothered to organize or label the tablets by location of excavation prior to shipping them across the world. Lots of enthusiastic folks got to work.

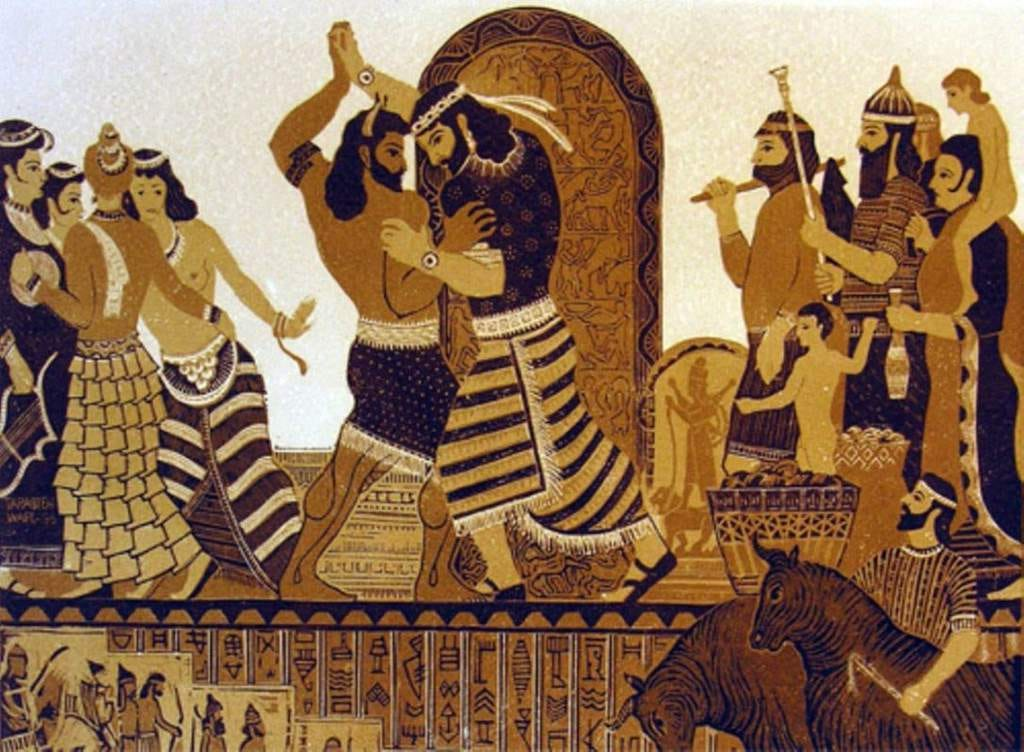

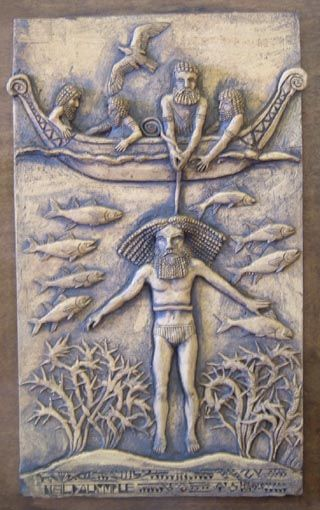

George Smith stumbled across the story of Utnapishtim, a man granted immortality by the Mesopotamian gods for salvaging a remnant of humanity and animal life from total destruction after one of their ranks, Enlil, unleashed an ill-advised flood. Utnapishtim isn’t privy to the exact rationale of the flood in this text, but one of the other gods, Ea, warns him of its coming. He constructs a large multi-level ship. As the rains pour down he gathers friends, relatives, and animals into the boat. After the flood waters recede the ship runs aground on a mountain, and he sends out a progression of birds to determine when it’s safe to disembark. When he and his shipmates emerge he offers sacrifices to the gods, and because he’s all that’s left of the worshiping public, all the gods show up. The major players of the pantheon chastise Enlil saying that he could have achieved his ends of punishing evildoers in any number of less arbitrary ways. Because of his pivotal role in preserving humanity Utnapishtim and his wife are granted immortality.

Those of you familiar with Genesis 6-9 recognize elements of this story. So did George, which led directly to the meeting 3 Dec 1872.

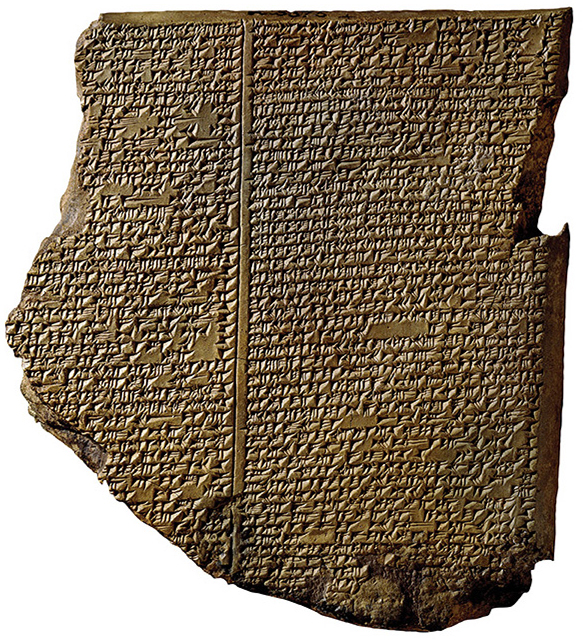

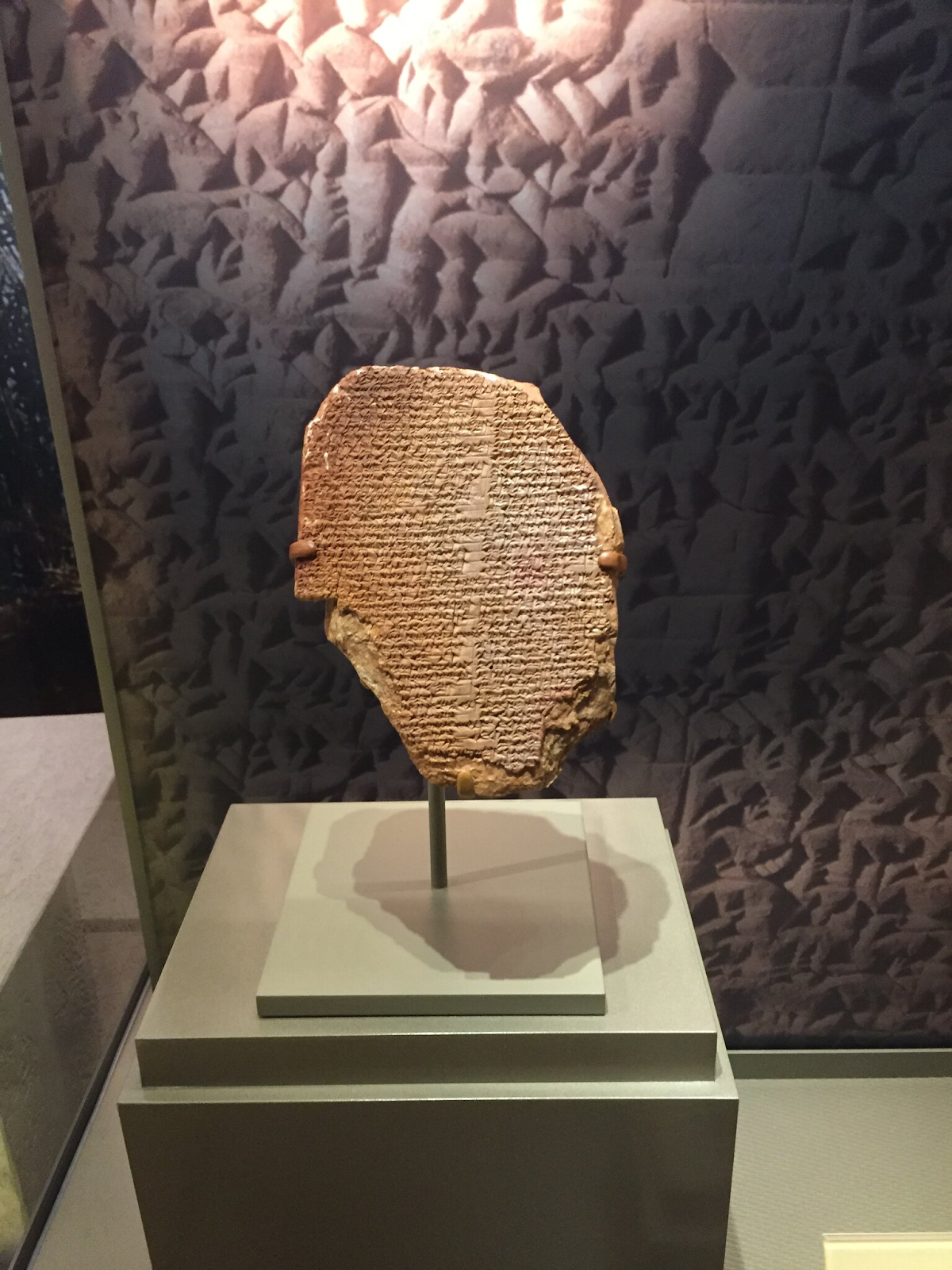

The thing is, while clay tablets are better than organic media for storing information for thousands of years, they’re brittle, and the tablet he had translated was missing fragments. He was immediately sponsored to find more tablets and fragments, and in an unlikely turn of incredible good luck, on his first expedition to Mesopotamia he found what he was looking for. Providence was clearly on this man’s side.

In the years since his initial translation, many more tablets related to the one he stumbled upon have been found and translated, and it turns out the story of Utnapishtim is part of a larger epic of which the flood narrative is only a relatively minor subplot. A more complete Mesopotamian flood narrative can be found in a story called Atrahasis. None of this dampens the potential meaning of the tablets for folks who find the similarities to the Bible heartening. The proprietors of Hobby Lobby bought a Babylonian tablet containing part of the story at auction for 1.67 million dollars in 2014 and displayed it in the Museum of The Bible in Washington DC. It turns out that the tablet had been smuggled out of Iraq illegally (I’ll avoid a discussion of the “legality” of how the British Museum obtained and maintains its collection) and it was seized by the FBI in 2019 and eventually repatriated to Iraq. This is to say people are still very much attached to this specific story. Some interpret the existence of flood narratives in Mesopotamia similar to that of The Bible as confirmation of the historicity of the biblical flood account. Mesopotamia isn’t the only culture that told flood myths. Greeks, Chinese and tribal stories in The Americas all have flood myths. They don’t necessarily line up chronologically, but, for some, the ubiquity of flood myths around the world opens the door to a belief in the legitimacy of the Noachian deluge.

Alternatively, the fact that the Mesopotamian texts are older than any extant biblical manuscripts, and the fact that there are tablets bearing the Mesopotamian stories in the levant and as far away as Anatolia, in addition to a well documented sojourn of Israelite peoples in Assyria and Babylon all raise the possibility that the cultural exchange flowed in a different direction. Periodic, destructive, local flooding in relatively isolated pre-literate communities could understandably give rise to ubiquitous flood narratives of independent origin. I don’t think there is any way to definitively answer these questions, and to be honest it doesn’t interest me very much, and it’s not what I want to talk about. It’s not even the most interesting biblical comparison worth considering in the text in question. What George Smith found was far more interesting and profound than a proof or counter narrative to the Bible. He found what would come to be known as tablet XI of The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Waynaboozhoo and The Great Flood

Without further ado, let’s talk about our boy Gilgamesh and his journey.

The tablet George Smith translated was the 11th of a set of 12 that form what is now known as the “Standard Version” of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Where it was found suggests that it was written down by at least 700 BCE, but excavations and discoveries made since suggest the Standard Version was composed between the 13th and 10th centuries BCE and is attributed to a person named Sin-Liqe-Unninni. The general consensus is that the “original” Standard Version text is accounted for by tablets I-XI of the Nineveh find, and that tablet XII was a later edition whose style and content don’t match with the overall arc of the epic. This checks out on my reading.

Over the past century and a half many other tablets containing tales of Gilgamesh and his bestie Enkidu have been found all over Mesopotamia, the Levant, and as far away as Arabia, and modern Turkey. Some of these tablets date to before 2000 BCE. Some of the stories on these older tablets are similar to the standard version, some lie completely outside that narrative. The longest of these non-standard version stories is what is called The Old Babylonian Version, which pre-dates the Standard Version by about 1000 years. None of the versions are complete, but there is enough overlap to feel confident we’re dealing with a well known hero and a story that was shared over a very long time across an expansive territory. People dug Gilgamesh for a very long time.

The number and variety of Gilgamesh stories presents a challenge to modern folks who tend to like definitive, authoritative, and “official” versions of things. The fragmentary nature of the available texts denies us that feeling of objective reality we so enjoy. On the other hand we get a glimpse of the evolution of the characters and story over time and can appreciate the artistry of altering and interweaving individual tales to compose the epic which is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s a reminder of how many ancient texts we think of as authoritative are outgrowths of oral traditions and change over time and place to serve the needs of the storyteller and audience. It provides a limited retrospective on the human penchant for myth making and I think offers caution about using any ancient resource as a proof text.

Because no single source is complete, translators looking to “tell the tale” of Gilgamesh must make editorial choices. In her Oxford World Classics edition Myths From Mesopotamia, Stephanie Dalley makes the somewhat obvious choice to provide the reader with translations of available tablets without any source integration while noting where and how large the gaps in the source material are. This approach provides readers with an appreciation of exactly what the primary sources contain, and an insight into the effort and editorial decisions made by others who chose to integrate multiple sources. It also gives readers the freedom to construct a narrative as they see fit. It’s straightforward and helpful for study of the evolution of content, but some of the sections are so fragmentary it can make understanding the narrative arc difficult unless one is already familiar with the content. On the other end Stephen Mitchell’s approach of liberally combining sources to maximize richness of narrative makes the story come alive, but presents a version which may or may not have ever existed. Some find this editorialization bothersome. Since there is no definitive “version” to begin with, I don’t mind this, but with no knowledge of the sources upon which he is drawing a reader may feel unsure whether or not one is getting the genuine article. How much of his rendering is the ancient tale, and how much is Stephen Mitchell? The answer is that the vast majority is ancient material, but I only know that because I’ve spent a fair amount of time with other versions of the story.

The middle ground is represented by Andrew George’s text whose most recent edition is published by Penguin Press, and Benjamin Foster’s rendering for Norton. Andrew George fills in gaps where repetition of phrases within the text make it highly likely that a specific phrase is being repeated based on what is present. He also makes some editorial editions, what he calls “reconstructions” to the “Standard Version” from recently discovered fragments including those of the “Old Babylonian Version” when merited by similarities between texts. He also offers suggestions about where alternative sources may be used to fill gaps in the Standard version texts, but he doesn’t always include them in his rendering of “The Standard Version”. He includes translations of these alternative sources in the book. The result is similar to Staphanie Dalley’s work; the reader is provided the resources to construct their own version based upon individual sources. Many new tablet fragments have been identified since Dalley’s work, so the narrative feels more complete and in my opinion provides a more enjoyable experience for the lay reader. The Standard Version he provides is very readable and the other source material he provides is instructive, and as best as I can tell his work is considered fairly authoritative. Benjamin Foster’s approach is a bit closer to Stephen Mitchell’s. He essentially makes the leap of including the bits George leaves out, this enriches the narrative and his version is very similar in content to Mitchell’s, the main distinction being that Foster’s additions and sources are explicitly noted in the text while Mitchell outlines his method in a preface.

Reading four translations may sound like a lot, but it’s not. The story is only like 40 pages long so it’s not some miraculous feat of endurance or scholarship on my part. I think it is evidence of curiosity and the compelling nature of the story. For the record I enjoyed Foster’s approach best. I took the most notes in the Mitchell and George editions, but I suspect that is because I read them 3rd and 4th respectively. If you’re in the mood for an easy read I’d definitely go with Mitchell or Foster. I’ll probably quote from everyone except Dalley. Her approach has merit, but it was definitely the most challenging to get through. I read it first not knowing all this, and that was almost certainly a mistake. Having her edition around has been useful for cultural background from other Mesopotamian myths, so I still feel like my $12.99 wasn’t wasted. This is all to say when one discusses Gilgamesh, one must make decisions about what to discuss and how. I will discuss Gilgamesh as an integrated narrative as presented by Foster and Mitchell. With a single exception, I don’t plan on alerting the reader to which source tablet is being used as I move through the story, and the rationale for that exception will be obvious.

Another aspect worth considering is what, if any, resemblance to historical reality do the tales of Gilgamesh bear? Was Gilgamesh a real person? The man described in the text is a king of the city Uruk. Uruk is well attested in the historical and archeological record and lies along the Euphrates River, under the present city of Warka, Iraq. It definitely had kings in the 3rd millennium BCE. Locally excavated materials even list Gilgamesh as a king and report he built the walls of Uruk. Inscriptions written by rival kings in other cities talk about laying siege to Uruk while Gilgamesh was king. Several ancient Mesopotamian “king lists” which were used to track dates, and establish legitimacy of rulers name Gilgamesh as king of Uruk during what is known as the early dynastic period. So it is plausible that Gilgamesh was in fact a real person and king of Uruk in the ballpark of 4500 years ago.

On the other hand, one of the main identifiers of Gilgamesh in the epic is the claim that he built the walls of Uruk. Are we in a: Daedalus designed and built a labyrinth under a Minoan palace in Knossos situation here? Even the oldest king lists noted above were compiled hundreds of years after Gilgamesh’s purported life and times. I noted rulers used these king lists to legitimize their own reigns which is to say they were propaganda, like the Ethiopian Solomonic Dynasty. Similarly, claiming that you’ve laid siege to the city of a king of legendary stature has got to have significant PR value. Consequently, we must approach these strands of evidence with some skepticism. As is so often the case one cannot be certain of the historicity of the individual in question. Most folks tend to come down on the side of it being likely there once was a king of Uruk bearing a name something like Gilgamesh, but that his story is shrouded in time and legend and the kernel of his truth cannot be known or extracted from the available evidence or legend. Like King Arthur in Britain, this is fertile ground for speculation and myth making. Let’s get to it already Mark.

The Epic of Gilgamesh opens in praise of the eponymous character. There is some debate about the meaning of the name Gilgamesh. Most translations describe him as “He who saw into the abyss”, or “He who has seen the depths”. The praise foreshadows the journey outlined in the narrative: his conquests, his travels over mountains, across land, and overseas, and his restoration of religious mysteries of ancient date. However, the best developed image is that of the great walled city of Uruk.

He who saw the wellspring, the foundations of the land who knew the world’s ways, was wise in all things…

He it was who studied seats of power everywhere, full knowledge of it all he gained.

He saw what was secret and revealed what was hidden, he brought back tidings from before the Flood,

from a distant journey came home, weary, but at peace, set out all his hardships on a monument of stone.

He built the walls of ramparted Uruk… see its upper wall, which girds it like a cord, gaze at the lower course, which no one can equal, mount the wooden staircase there from days of old…

Go up, pace out the walls of Uruk, study the foundation terrace and examine the brickwork.

Is not its masonry of kiln-fired brick?

And did not seven masters lay its foundations?

One square mile of city, one square mile of gardens, one square mile of clay pits, a half square mile of Ishtar’s dwelling.

Three and a half square miles is the measure of Uruk! (Foster)

Our attention is directed to a box, a time capsule, buried inside one of the bricks that form the foundation of the mighty walls, and tablets stored in the box. The tablets contain the story of the man who built these fabulous walls that protect this great city.

Gilgamesh is bigger, stronger, and more energetic than any man alive. Like many ancient heroes he is a demigod of unique proportions; we are assured he is two-thirds god, and one-third human. Let’s see Gregor Mendel and his wrinkly peas sort that one out. The math may or may not be similar to the story of the conception of Theseus in Greek myth. His ambition and desires are boundless. His demands “wear out” the men and women over which he rules. They pray to the Mesopotamian gods that he be humbled. Surprisingly, the gods hear these cries and a plan is hatched to bring Gilgamesh to heel.

I say surprisingly because Mesoptamian gods were not believed to be particularly benevolent. As we all learn in World History class, the Nile flooded gently and predictably on an annual basis depositing rich soil that supported agriculture and civilization. There’s a claim that the predictability of the Nile shaped the Egyptian world view as suggested by an orderly pantheon featuring gods who personally ruled and shepherded the people. The flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers was erratic and sometimes violent. Harnessing their life-giving water was done with levies, and canals requiring enormous amounts of human labor. Like other polytheistic pantheons, the Mesopotamian creation story involves multiple generations of gods and intergenerational conflict. One of the drivers of that conflict was that younger generations of gods got saddled with the physical labor of maintaining divine order, and resented it. Humans were created with the specific goal of unburdening the gods of that labor. The toil of canal maintenance, irrigation, and agriculture with the aim of producing agricultural surplus to sacrifice to the gods is the whole point of human existence. All to say that it isn’t a given that the gods would pay any notice to the complaints from Gilgamesh’s people in Uruk.

The gods craft a man from clay. Enkidu is also bigger, faster, and stronger than other men. He runs with the herds of wild animals, he eats grass and drinks from watering holes with them. He is covered in fur, and while he behaves like an animal he seems to have some understanding because he thwarts the efforts of local hunters by disabling their traps. One day a young hunter sees and fears Enkidu. He seeks counsel from his father and is in turn sent to Uruk to find the means of subduing this man beast. The young hunter is advised to bring Shamhat, a prostitute at the temple of Ishtar, out from the city to tempt and tame Enkidu. She is successful.

Shamhat loosened her garments, she opened her loins, he took her charms, she was not bashful, she took his vitality.

Six days, seven nights was Enkidu aroused, flowing into Shamhat. (Foster)

Once he has enjoyed the seductive charm of a woman Enkidu is rejected by the animals, his legs cannot keep pace with the herds, but he develops wisdom and understanding.

His knees stood still, while his beasts were going away, Enkidu was too slow, he could not run as before, but he had gained reason, broadened his understanding… Enkidu, you are become like a god (Foster)

He cleaves to Shamhat and she further civilizes him. The extreme makeover is on. He gets a haircut, he begins wearing clothes, and takes to eating bread and drinking beer.

Eat the bread, Enkidu, the staff of life, drink the beer, the custom of the land.

Enkidu ate the bread until he was sated, he drank seven juglets of the beer.

His mood became relaxed , he was singing joyously, he felt lighthearted and his features glowed.

A barber treated his hairy body, he anointed himself with oil, turned into a man, he put on clothing, became like a warrior. (Foster)

He becomes a boon to local herders, but he desperately wants a friend. One day he hears about the outrages of Gilgamesh; a herder is on his way to Uruk to celebrate a wedding and lets slip that Gilgamesh has proclaimed “first night rights” upon the newlyweds of Uruk.

At the man’s account, his face went pale. (Foster)

We have a Braveheart situation to address. Enkidu rushes to the city to confront Gilgamesh.

Meanwhile, Gilgamesh is having troubling dreams. On successive nights he has visions of a meteor and an ax falling from the sky that astound his people. In both dreams Gilgamesh attempts to subdue the falling object, and he ends up embracing it. He doesn’t know the meaning of these dreams, but his mother, the goddess Ninsun, assures him these mean that he will soon meet a companion who will protect him and will be a great friend.

Enkidu arrives in Uruk and the city is amazed by his greatness, the citizens throng the streets to celebrate him wherever he goes. The wedding is celebrated shortly after his arrival and as Gilgamesh steps forward to assert his dominance and insert himself into the bridal bed chamber Enkidu challenges him. Combat ensues [insert Marvel or DC action sequences of infrastructure destruction here] and when the dust settles Gilgamesh holds Enkidu over his head. He remains undefeated.

This launches the buddy comedy portion of the story. It turns out Gilgamesh really needed a friend too. He harbors ambitions that look beyond the boundaries of Uruk, and now that he has someone as impetuous, energetic, and physically imposing as himself, Gilgamesh hatches a plan.

They’ll go to the forests in the far distant mountains of Lebanon, conquer Humbaba, the guardian of the forest, and return with the lumber needed to complete construction projects Gilgamesh has had on the back burner. Solomon knows all about the desirability of Lebanese cedarwood. They alternate periods of anxiety and certainty throughout their journey to the forest, but ultimately face and conquer Humbaba together, and help themselves to massive quantities of lumber.

My friend, we have made a wasteland of the forest, my friend we have felled the lofty cedar, whose crown once pierced the sky.

Now make a door of cedar six times twelve cubits high, two times twelve cubits wide, one cubit shall be its thickness. (Foster)

They return to Uruk in triumph.

There’s nothing ladies and gods love more than a conquering hero, and Gilgamesh catches the eye of no less than the goddess Ishtar. She offers herself to him, but Gilgamesh refuses her.

Why would I want to be the lover of a broken oven that fails in the cold, a flimsy door that the wind blows through, a palace that falls on its staunchest defenders, a mouse that gnaws through its this reed shelter, tar that blacken’s the workman’s hands, a waterskin that is full of holes and leaks all over its bearer, a piece of limestone that crumbles and undermines a solid stone wall, a battering ram that knocks down the rampart of an allied city, a shoe that mangles its owner’s foot?

Which of your husbands did you love forever?

Which could satisfy your endless desires?

Let me remind you of how they suffered, how each one came to a bitter end. (Mitchell)

There’s a saying about the fury of a scorned woman and Ishtar does not disappoint. She goes to her father and demands that he send down “The Bull of Heaven” to punish Gilgamesh and his people.

There is chaos when The Bull arrives. Intrepid Enkidu literally takes the bull by the horns in an effort to gain some sort of control over it. He identifies the Bull’s vulnerabilities and Gilgamesh deliver’s the knockout blow.

[Enkidu] jumped out and grabbed the Bull’s horns, it spat its slobber into his face, it lifted its tail and spewed dung all over him.

Gilgamesh rushed in and shouted, “Dear friend, keep fighting, together we are sure to win.”

Enkidu circled behind the Bull, seized it by the tail and set his foot on its haunch, then Gilgamesh skillfully, like a butcher, strode up and thrust his knife between its shoulders and the base of its horns.

After they had killed the Bull of Heaven, they ripped out its heart and they offered it to Shamhash…

[Enkidu] reached down, ripped off one of the Bull’s thighs and flung it in Ishtar’s face.

“If only I could catch you, this is what I would do to you, I would rip you apart and drape the Bull’s guts over your arms!” (Mitchell)

These two are greater than their fellow men, together they conquer the natural world, and even defy the gods themselves. Something has got to give. The gods hold council and Enkidu is sentenced to death.

Enkidu has a dream where he learns this judgment, sees his own death, and has a very unflattering vision of the afterlife. In fact he has a whole series of dreams. Gilgamesh is in denial and laughs off his friend’s anxiety offering a variety of interpretations of the dreams. Nonetheless, over 12 days Enkidu wastes away and dies. Gilgamesh remains in denial and holds his friend’s corpse for another week and only accepts the reality of his death when maggots fall from his nostrils.

Gilgamesh orders a memorial fit for a king. Statues are commissioned, and treasures are fashioned to accompany Enkidu to the afterlife. While he has finally reconciled himself to Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh confronts his own mortality for the first time. He is distraught and sets off from Uruk in search of immortality. He crosses the continents, mountain passes, and even braves the tunnel under the earth that the Sun uses every night to transit back from where it sets in the west to where it rises in the east. #FlatEarthProblems. He has heard that one man, Utnapishtim, has gained immortality and wants to understand the secret so that he will never die. Finally he arrives at the western edge of the world, on the shore of a great sea. He knows that Utnapishtim lives somewhere on the other side of the ocean. Conveniently there is a tavern on the beach at the edge of the world. A restaurant at the end of the universe. Shiduri, the tavern keeper goddess, warns Gilgamesh that his quest is in vain, but ultimately tells him that Utnapishtim periodically receives a single visitor, the Ferryman Urshanabi.

Gilgamesh tracks down Urshanabi, intent on forcing the Ferryman to transport him across the waters. Urshanabi doesn’t roll solo, but the mighty Gilgamesh defeats his crew of stone people. Urshanabi relents and tells Gilgamesh he’ll take him wherever he wants to go. His face sinks when he learns Gilgamesh wants to visit Utnapishtim. It turns out to get to Utnapishtim one must cross “the waters of death”, and even touching these waters is fatal. Their invulnerability to these waters is what made Urshanabi’s crew of stone people so valuable. Oops. In the end a system is developed to get across the waters of death and Gilgamesh arrives on Utnapishtim’s shores.

Gilgamesh converses with Utnapishtim, and this is the part that so excited George Smith. The story involves humans making too much noise and the gods’ need to get some sleep, the plan for a flood is hatched. A single benevolent god Ea determines to save a remnant of mankind. Whispering fences and walls, construction of an arc, lots of rain, and few birds are involved in the salvation of humanity. Utnapishtim is granted immortality because despite this admittedly terrible plan, he remains faithful to the gods and continues to sacrifice to them. The circumstances are such that they cannot be readily duplicated by a mortal, so Gilgamesh is out of luck. Immortality must be more than meets the eye because Utanpishtim seeks to prove that even given the opportunity, Gilgamesh couldn’t hack it. Mortals need rest, Gilgamesh is such a weak mortal he couldn’t even stay awake for 7 days. Gilgamesh accepts the challenge, and promptly falls asleep. He sleeps for 7 days and when he awakes he accepts that what he seeks, he will not find, and Utnapishtim cannot give it to him. Utnapishtim gives him some advice about how to live and rule and sends him away.

As a parting gift he tells Gilgamesh of a plant that grows at the bottom of the sea whose leaves, if eaten, will make an old man young again. Gilgamesh dives down and emerges with the plant. As heroes often inexplicably do, after journeying so far and risking so much he suddenly becomes cautious and doesn’t immediately eat the leaves. He decides that he’ll return to Uruk and have an old man there try it first. If it works then he’ll eat some too. On the journey back a snake eats the plant while it sits unattended and as it slithers away it sheds its old skin. Curses, foiled again.

The story closes as Gilgamesh returns within sight of Uruk. He contemplates the majesty of the city. Its size, its people, its temples and orchards, and most of all, those imposing walls.

When they arrived in ramparted Uruk, Gilgamesh said to him, Urshanabi the boatman:

Go up, Urshanabi, pace out the walls of Uruk.

Study the foundation terrace and examine the brickwork.

Is not its masonry of kiln-fired brick?

And did not seven masters lay its foundations?

One square mile of city, one square mile of gardens, one square mile of clay pits, a half square mile of Ishtar’s dwelling.

Three and a half square miles is the measure of Uruk! (Foster)

It’s not particularly long. There’s basically no “world building” and character development is uneven. Despite all the tablets that have been found and translated, there are several gaps in the story, among these gaps are parts of Gilgamesh’s final conversation with Urshanabi as they approach the walls of Uruk. Apart from its antiquity and quirky history of its reemergence in the 19th century, is this story worth a person’s time? Aside from saying you’ve read what is generally considered the oldest piece of literature in the western tradition, is there any value in the text? Ultimately that’s up to the reader to judge.

I enjoy reading texts of ancient literature for several reasons. One of them is that they make me feel a kinship with my fellow humans. Across time and space we wrestle with some of the same concerns, and we share insights into how to address them. I also like seeing how aspects unique to specific cultures interact with universal themes. With those thoughts in mind I found Gilgamesh to be a rewarding read. But I could probably stretch a discussion of Little Red Riding Hood into a multi-part blog post if I wanted to, so my opinion may not be worth much. I’m pretty sure I could break out at least 5,000 words on the female characters in Gilgamesh: Shamhat, Ishtar, Shiduri and Utnapishtim’s wife all play pivotal roles in the narrative. While Gilgamesh doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test, the fact that there are nearly as many named human female characters as there are male is a pleasant surprise for someone who spent the last few months in the land of The Iliad. I would like to discuss three aspects of the epic in more detail. First off, the character arc of Enkidu and his relationship with Gilgamesh is interesting and well done. Second, the fall Gilgamesh endures in response to Enkidu’s death is worth considering. Finally, I think there’s a fun way to frame the wisdom the Epic offers on how to live one’s life. I’m nearly 5,000 words in already and this feels like a good place to stop for now.